The Enduring Enigma: Exploring the Philosophical Idea of the Body and Soul

The philosophical inquiry into the idea of the body and soul stands as one of humanity's most persistent and profound questions. At its core, this philosophy grapples with the fundamental nature of human existence: Are we merely physical beings, or is there an immaterial essence—a soul or mind—that animates our flesh? This article delves into the historical evolution of this intricate debate, tracing its origins from ancient Greek thought through the medieval period and into modern philosophy, drawing heavily from the foundational texts compiled in the Great Books of the Western World. Understanding this relationship is not merely an academic exercise; it underpins our concepts of identity, morality, consciousness, and the very meaning of life and death.

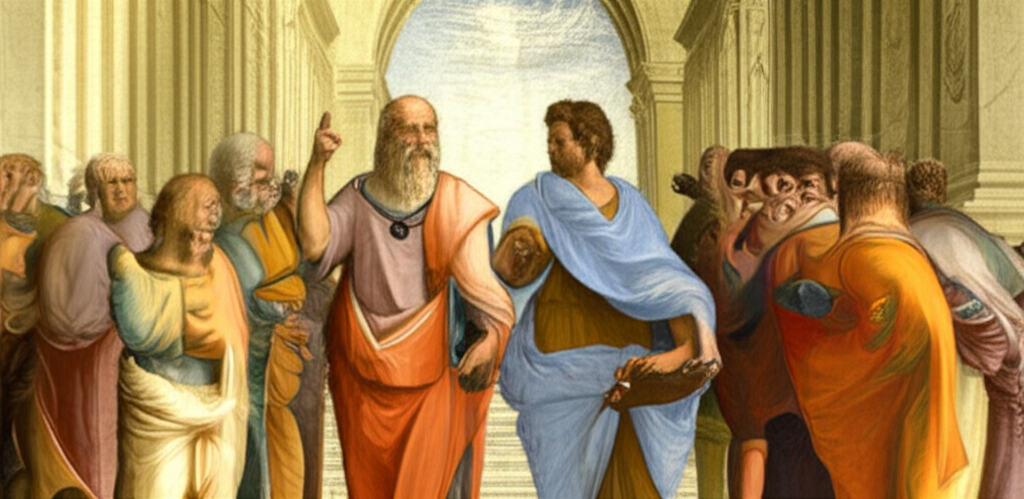

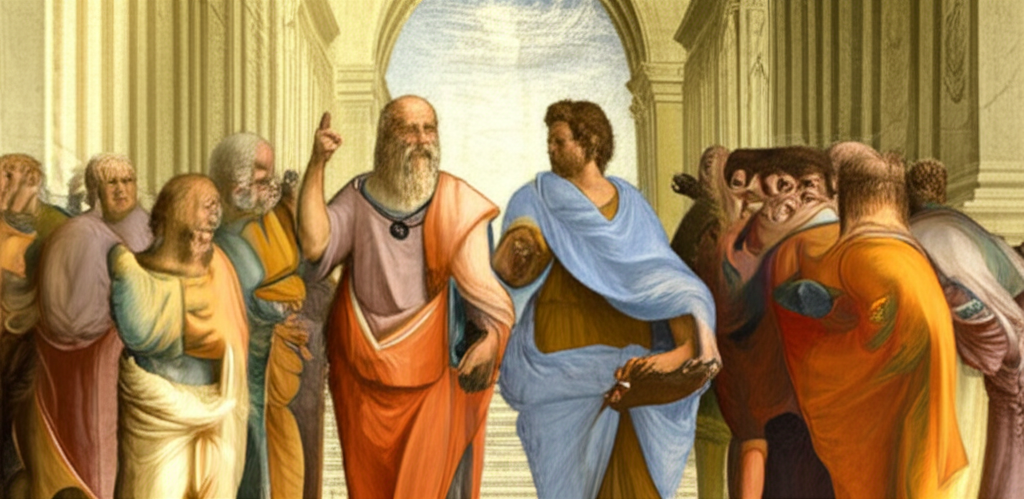

I. Ancient Roots: Dualism's Dawn

The earliest Western philosophical traditions laid the groundwork for the enduring discussion of the body and soul, introducing concepts that continue to resonate today.

Plato's Ideal Forms and the Immortal Soul

For Plato, as explored in dialogues like the Phaedo and the Republic, the soul is distinct, immaterial, and immortal, trapped within the mortal body. The body is seen as a source of desires, distractions, and limitations, while the soul (specifically its rational part) yearns for the realm of eternal, unchanging Forms—Truth, Beauty, Goodness. Plato’s idea is that true knowledge comes from the soul's recollection of these Forms, suggesting the soul's pre-existence and its capacity for a life beyond the physical. Death, for Plato, is the liberation of the soul from the body's prison.

Aristotle's Hylomorphism: Soul as Form of the Body

Aristotle, a student of Plato, offered a more integrated, yet still complex, perspective. In De Anima (On the Soul), he rejected the notion of the soul as an entirely separate entity. Instead, he proposed hylomorphism, the idea that the soul is the "form" (essence or actuality) of a natural body possessing life potentially. Just as the shape of an axe is its form and its material is the wood and metal, the soul is the organizing principle of the living body. It is what makes a living thing alive, enabling its functions like nutrition, sensation, and thought. While he saw the nutritive and sensitive parts of the soul as inseparable from the body, Aristotle left open the possibility that the intellective or rational part of the human soul might be separable and immortal, a point of much subsequent debate.

II. Medieval Synthesis: Theological Dimensions

The advent of Christianity significantly reshaped the philosophical discourse on the body and soul, integrating classical philosophy with theological doctrines.

Augustine's Christian Platonism

Saint Augustine of Hippo, profoundly influenced by Plato, articulated a powerful Christian dualism. In works like Confessions and City of God, he viewed the soul as an immaterial substance, created by God, distinct from and superior to the body. The body is the "house" or "prison" of the soul, yet Augustine also insisted on the goodness of creation, including the body, as God's handiwork. He emphasized the soul's capacity for introspection, self-knowledge, and its direct relationship with God, making it the seat of personal identity and moral agency. The ultimate destiny of both body and soul was a central theological concern.

Aquinas and Aristotelian Influence

Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, meticulously synthesized Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. He adopted Aristotle's hylomorphism, asserting that the human soul is the substantial form of the human body, making the human being a unified composite of matter and form. This meant the soul is not merely a pilot guiding a ship (Plato's analogy), but intrinsically united with the body, giving it its specific human nature. However, Aquinas diverged from Aristotle by asserting the soul's independent subsistence and immortality, particularly its intellectual faculty, which he argued could operate independently of the body's organs. This complex idea allowed for both the unity of the human person and the possibility of individual survival after death.

III. The Dawn of Modernity: Descartes and the Mind-Body Problem

The modern era ushered in a new level of scrutiny, particularly with René Descartes, whose work profoundly shaped subsequent philosophical inquiry.

Cartesian Dualism: Res Cogitans and Res Extensa

René Descartes, considered the father of modern philosophy, famously articulated a radical form of substance dualism in his Meditations on First Philosophy. He posited two fundamentally different kinds of substances:

- Res Cogitans (Thinking Substance): This is the mind or soul, characterized by thought, consciousness, and lacking spatial extension.

- Res Extensa (Extended Substance): This is the body, characterized by extension in space, motion, and lacking thought.

For Descartes, the idea of the soul (or mind) is more certainly known than the body, leading to his famous "Cogito, ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am"). The problem, which plagued Descartes and his successors, was how these two utterly distinct substances—an unextended thinking thing and an unthinking extended thing—could possibly interact. He famously suggested the pineal gland as the point of interaction, but this explanation remained unsatisfactory for many.

Challenges and Alternatives

Descartes' dualism, while influential, immediately faced challenges. Philosophers like Spinoza and Leibniz proposed alternative monistic or pluralistic views to address the interaction problem. Spinoza suggested a single substance with infinite attributes (mind and body being two of them), while Leibniz posited monads, individual unextended substances that "mirror" each other in pre-established harmony, avoiding direct interaction. The "mind-body problem" became a central concern, pushing philosophy towards exploring materialism, idealism, and various forms of monism in the centuries that followed.

IV. Contemporary Perspectives: Beyond Traditional Dualism

While traditional dualism still has proponents, contemporary philosophy has largely moved towards more nuanced or alternative explanations.

Materialism and Physicalism

Many contemporary philosophers adopt a materialist or physicalist stance, arguing that mental phenomena (the "soul" or mind) are entirely products of the body, specifically the brain. This idea suggests that there is no separate, immaterial substance; consciousness and thought are simply emergent properties of complex neural activity. Various forms exist, from identity theory (mental states are brain states) to functionalism (mental states are defined by their causal roles, which can be realized by physical systems).

Emergentism and Other Non-Reductive Approaches

Some non-reductive physicalists propose emergentism, the idea that consciousness and mental properties "emerge" from the complex organization of physical matter (the brain) but cannot be fully reduced to or explained solely by their constituent physical parts. These emergent properties are real and have causal efficacy, even if they arise from the physical. Other approaches include panpsychism (the idea that consciousness is a fundamental property of all matter) and various forms of property dualism, which suggest that while there's only one substance (physical), there are two distinct kinds of properties (physical and mental).

V. The Enduring Significance of the Debate

The philosophical inquiry into the idea of the body and soul is far from resolved, continuing to shape our understanding of ourselves and the world.

Implications for Ethics, Identity, and Afterlife

How we conceptualize the relationship between our physical form and our inner life has profound implications:

- Personal Identity: If the soul is distinct and immortal, does it carry our identity beyond the body? If identity is tied to the brain, what happens if the brain changes or deteriorates?

- Moral Responsibility: Does the soul provide the seat of free will, making us morally accountable? Or are our actions determined by our physical makeup and environment?

- The Afterlife: The existence of an immaterial soul is often a prerequisite for beliefs in an afterlife, reincarnation, or spiritual existence beyond physical death.

- Consciousness: Understanding the nature of the soul is intrinsically linked to the "hard problem of consciousness"—how physical matter gives rise to subjective experience.

The Philosophical Quest Continues

From the ancient Greeks pondering the essence of being to modern neuroscientists exploring the brain's complexities, the idea of the body and soul remains a central pillar of philosophy. It challenges us to look inward and outward, to question our assumptions, and to continue the timeless quest for self-understanding. The Great Books of the Western World serve as an invaluable guide, revealing the persistent threads of this inquiry through millennia of human thought.

Philosophical Perspectives on Body and Soul: A Brief Overview

| Philosopher/School | Core Idea of Soul | Core Idea of Body | Relationship | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Immortal, immaterial, pre-existent, yearns for Forms | Mortal, material, prison for the soul, source of distraction | Dualistic (Soul superior to Body) | Knowledge as recollection, afterlife, moral purification |

| Aristotle | Form/actuality of the body, inseparable (mostly); intellect potentially separable | Matter/potentiality, necessary for soul's expression | Hylomorphic (Soul and Body form a unity) | Soul enables life functions, human as composite being |

| Augustine | Immaterial, created by God, seat of identity, immortal | Material, created good, house for the soul, subject to sin | Dualistic (Soul superior but Body is good) | Free will, sin, salvation, direct relation to God |

| Descartes | Res Cogitans (thinking substance), unextended, immortal | Res Extensa (extended substance), unthinking, mortal | Radical Dualism (Two distinct substances, interaction problem) | "Mind-Body Problem," consciousness as primary, mechanistic view of body |

| Modern Physicalism | Mental states are brain states/processes, no separate soul | The entirety of human being, including consciousness | Monistic (Mental reduces to Physical) | Scientific explanation of consciousness, no afterlife (typically) |

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Dualism and the Soul Crash Course Philosophy #10""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Descartes and the Mind-Body Problem Explained Simply""