The Philosophical Basis of Liberty: A Journey Through Thought

Liberty, that cherished ideal, often feels like an innate desire, a natural state for Man. Yet, its understanding and actualization have been the subject of profound philosophical inquiry for millennia. This article delves into the rich intellectual tapestry woven by some of the greatest minds in the Western tradition, exploring how philosophy has sought to define, defend, and delineate liberty, examining its intricate relationship with law and the very nature of Man. From ancient city-states to the Enlightenment's grand pronouncements, we trace the evolution of this vital concept, revealing it not as a simple absence of constraint, but as a complex interplay of rights, responsibilities, and the structures that govern human society.

Unpacking Liberty: More Than Just Freedom

At its core, liberty might seem straightforward: the freedom to act, speak, and think as one chooses. However, the philosophical journey quickly reveals layers of complexity. Is liberty merely the absence of external coercion (negative liberty), or does it also encompass the capacity and opportunity to fulfill one's potential (positive liberty)? The Great Books of the Western World introduce us to thinkers who grappled with these distinctions long before modern terminology existed. They understood that true liberty for Man must consider not just what one is free from, but also what one is free to do, and how these freedoms are secured within a societal framework.

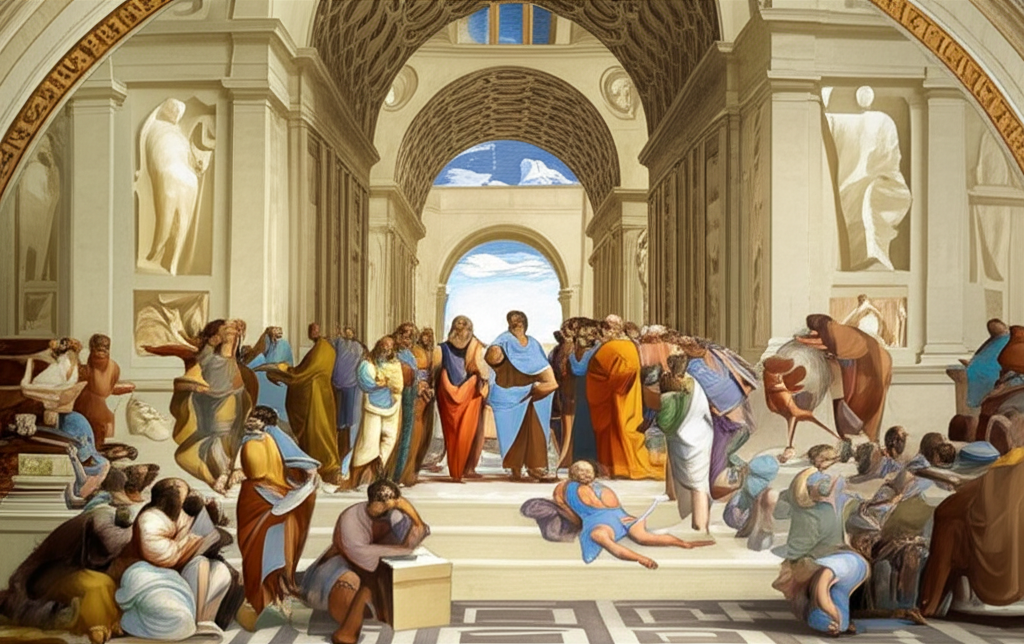

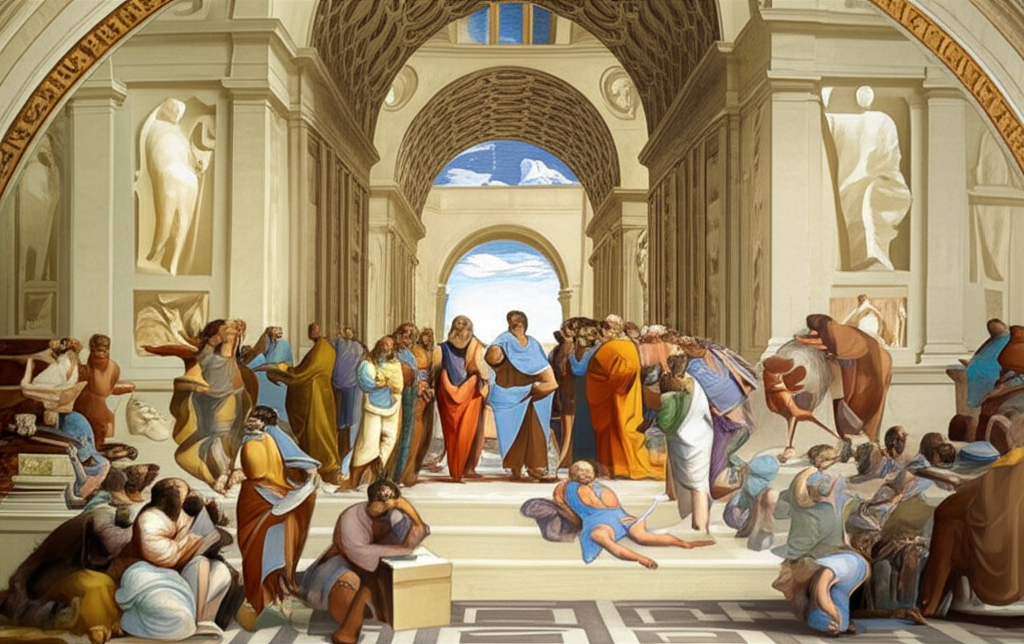

Ancient Roots: Plato, Aristotle, and the Polis

The earliest profound discussions of liberty often took place within the context of the polis, the Greek city-state. For philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, individual freedom was inextricably linked to the well-being and structure of the community.

- Plato, in works such as The Republic, explored the ideal state where justice and order reigned supreme. While not emphasizing individual liberty in the modern sense, his philosophy suggested that true freedom for Man lay in living a virtuous life guided by reason, often within the strictures of a well-ordered society. Too much unrestrained freedom, he argued, could lead to chaos and tyranny, ultimately diminishing genuine liberty.

- Aristotle, in Politics, further developed these ideas, positing that Man is by nature a "political animal." For him, flourishing, or eudaimonia, was achieved within the community, where citizens could participate in governance and live under just laws. Liberty, in this view, was not an escape from the law, but rather the freedom to live well under the law, which served to guide individuals towards their highest potential and ensure the stability of the state. The law was seen as a rational framework, not an arbitrary imposition, providing the conditions for a good life.

The Dawn of Modern Liberty: From Divine Right to Natural Rights

As Western thought progressed, particularly through the medieval period and into the Enlightenment, the concept of liberty underwent a radical transformation. The focus shifted from communal flourishing within a pre-ordained order to the inherent rights of the individual.

This era saw a profound re-evaluation of the relationship between Man, the state, and the law. Thinkers began to articulate a vision of liberty grounded in natural rights, often derived from a perceived "state of nature" and the concept of a social contract.

Key Enlightenment Contributions to Liberty:

- Thomas Hobbes (e.g., Leviathan): Though often seen as an advocate for absolute sovereignty, Hobbes's philosophy begins with a radical notion of individual liberty in the state of nature—a freedom so absolute it leads to a "war of all against all." For Man to escape this brutal existence, he argued, individuals voluntarily surrender some of their natural liberty to a sovereign power in exchange for security and order, establishing the law.

- John Locke (e.g., Two Treatises of Government): Locke presented a more optimistic view of the state of nature, where Man possesses natural rights to life, liberty, and property, governed by a natural law discoverable by reason. For Locke, government is formed by consent to protect these pre-existing rights, and its authority is limited. If the government oversteps its bounds and infringes upon Man's natural liberty, the people have a right to resist. His ideas profoundly influenced modern democratic thought and the concept of limited government.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (e.g., The Social Contract): Rousseau famously declared that "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains." He sought to reconcile individual liberty with collective authority, proposing that true freedom is found in obedience to a "general will"—a collective expression of the common good that all citizens participate in forming. For Rousseau, the law derived from this general will is not a constraint on liberty, but its very embodiment, allowing Man to be "forced to be free" by aligning individual desires with the greater good.

These philosophers, drawing heavily from reason and a burgeoning understanding of human nature, laid the groundwork for modern constitutionalism and the articulation of individual rights as fundamental to the concept of liberty.

Liberty and the Role of Law: A Necessary Tension?

The relationship between liberty and law is perhaps the most enduring philosophical puzzle. Is law a necessary evil, a bridle on our natural freedoms, or is it the very condition that makes true liberty possible?

- Immanuel Kant, a towering figure in philosophy, offered a sophisticated perspective. For Kant, true moral liberty (autonomy) is not merely the ability to do what one wants, but the capacity of Man to act according to self-imposed rational principles—the moral law. When individuals freely choose to follow universal moral principles, they are not constrained but are, in fact, realizing their highest form of freedom. Civil law, then, should ideally create the external conditions under which individuals can exercise this inner moral autonomy without infringing upon the equal liberty of others. The law becomes a guarantor of co-existence, allowing each Man to pursue his own ends within a framework of universal rights.

This perspective highlights that liberty without law often devolves into anarchy, where the strongest dominate, and the weakest have no freedom at all. Conversely, law without liberty becomes tyranny, stifling human spirit and potential. The philosophical quest has always been to find that delicate balance, that just framework where the law serves to expand, rather than diminish, genuine human liberty.

Modern Interpretations and Enduring Questions

The philosophical discussions on liberty continue to evolve, addressing new challenges posed by technology, global interconnectedness, and shifting social norms. Yet, the foundational questions articulated by the thinkers in the Great Books remain profoundly relevant:

- What constitutes true liberty for Man in a complex society?

- How much individual liberty can be reconciled with the demands of collective security and welfare?

- What is the legitimate scope of the law in regulating personal conduct versus protecting fundamental freedoms?

- Are there universal principles of liberty that transcend cultural and historical contexts?

These are not questions with easy answers, but their ongoing exploration through philosophy is crucial for any society striving to create a just and free existence for all. The journey through the philosophical basis of liberty is a testament to humanity's unending quest for self-understanding and the ideal society.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "John Locke Natural Rights Philosophy Explained"

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Kant's Categorical Imperative and Moral Law"