Introduction

In the realm of human psychology and social dynamics, a peculiar observation often emerges; individuals of lesser cognitive acuity frequently misconstrue the motivations of their more intellectually endowed counterparts. They assume that highly intelligent people are propelled by an ego-driven desire to assert dominance as the "smartest in the room." Yet, this perception could not be further from the truth. In reality, those possessing exceptional intelligence actively yearn for the experience of being the "dumbest" in the gathering, drawn by the unparalleled opportunities for intellectual growth & acute relief from the incessant demands of interacting with those of inferior cognitive capacity.

The thesis herein posits that genuine intelligence is characterized not by a quest for supremacy but by a naturally innate humility in the presence of superior minds. This orientation stems from two primary drivers: the intrinsic value of learning from those more adept & the psychological toll exacted by routine engagements with less capable individuals. To substantiate this, we will explore the cognitive biases that fuel misconceptions among the less intelligent, the empirical benefits of surrounding oneself with intellectual superiors, and the evidentiary support from scholarly studies. Through this analysis, the persuasive case will be made that embracing such a mindset is not merely preferable but essential for the personal and collective advancement of the smartest amongst us.

Misconceptions Rooted in Cognitive Biases: The Role of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

At the heart of the misunderstanding lies a well-documented cognitive bias known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, which illuminates why individuals of lower competence often harbor inflated views of their own abilities while projecting similar egocentric motivations onto others. First identified in 1999 by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, this effect describes a pattern wherein those with limited skills in a specific domain overestimate their proficiency, often dramatically, due to a lack of metacognitive awareness, the ability to accurately assess one's own competence. In their seminal experiments, participants in the bottom quartile of performance on tasks such as logical reasoning & grammar consistently rated themselves in the 62nd percentile, a gross overestimation that stems from an inability to recognize the qualitative gaps between their output & that of experts.

This bias extends beyond self-assessment to interpersonal perceptions. Less competent individuals, buoyed by their unwarranted confidence, frequently assume that others operate under the same paradigm of seeking validation through intellectual dominance. They project their own insecurities and desires onto highly intelligent people, convinced that the latter's drive is to be the unequivocal "smartest in the room." However, this is a fundamental misattribution. As Dunning and Kruger noted, the effect is domain-specific and not a blanket indictment of low intelligence leading to absolute overconfidence; rather, it highlights how incompetence breeds illusionary superiority. Popular culture often exacerbates this by simplifying the effect to "stupid people don't know they're stupid," which overlooks the nuance that even low performers do not claim equality with top experts but still overestimate relative to their actual standing.

Critics have proposed alternative explanations, such as statistical regression toward the mean and the "better-than-average" heuristic, where individuals inherently view themselves as superior to peers, creating patterns mimicking the effect without invoking metacognitive deficits. Nonetheless, these do not diminish the persuasive evidence that less intelligent individuals are prone to such biases, leading them to misinterpret the behaviors of their intellectual betters. For instance, in professional settings, this manifests as resentment toward experts who prioritize collaboration over competition, further entrenching the myth of ego-driven intelligence.

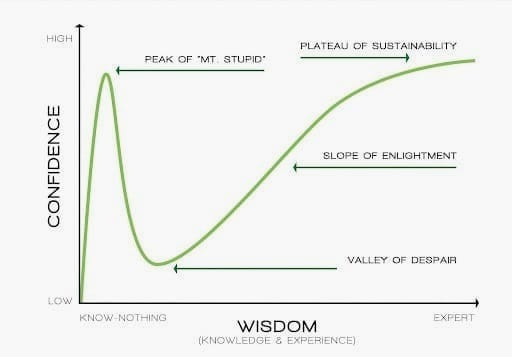

To visualize this phenomenon, consider the classic graphical representation of the Dunning-Kruger effect at the top of this article, which plots confidence against actual competence. The curve illustrates a peak of overconfidence among novices ("Mount Stupid"), followed by a valley of despair as awareness grows, and eventual ascent to sustained competence with moderated confidence.

The graph persuasively underscores why the less intelligent cling to their misconceptions, they reside at the peak, unaware of the vast landscape beyond.

The Allure of Intellectual Humility: Craving Learning Potential

Contrary to the projections of the less astute, highly intelligent individuals derive profound satisfaction from environments where they are outmatched intellectually. This craving is rooted in the exponential learning potential afforded by such settings. As the adage goes, "If you are the smartest person in the room, then you are in the wrong room," a sentiment variably attributed to Confucius & echoed by modern luminaries like Richard Feynman & Jack Welch. This principle is not mere aphorism but a strategic imperative for growth. Intelligent people recognize that stagnation ensues when one dominates discussions; instead, being the "dumbest" exposes them to novel ideas, rigorous debates, and paradigm-shifting insights.

Empirical support abounds. Longitudinal studies indicate that associating with more intelligent peers enhances one's own cognitive development. For example, research on adolescents revealed that having a best friend with higher intelligence in middle school correlates with elevated intelligence measures by high school, suggesting a contagious effect of intellectual environments. This peer influence operates through mechanisms like observational learning, constructive criticism & a motivation to bridge knowledge gaps. In professional contexts, leaders who deliberately surround themselves with superior talent foster innovation, as evidenced by case studies in business & academia where "being the dumbest in the room" catalyzes breakthroughs.

Moreover, this preference aligns with the psychological profile of high-IQ individuals, who often exhibit traits like openness to experience & a growth mindset, as per Carol Dweck's framework. They view challenges not as threats to ego but as avenues for expansion, demonstratively & persuasively arguing against the notion of dominance-seeking. Historical figures exemplify this: Albert Einstein frequently collaborated with peers like Niels Bohr, thriving in debates where his ideas were scrutinized, rather than isolating himself among admirers. Similarly, Marie Curie's partnerships in the scientific community underscore how intellectual humility accelerates discovery.

The Psychological Tolls of Intellectual Mismatch: Escaping the Burden

Equally compelling is a second facet: the desire to escape draining interactions, or the contemplation/anticipation of them, with less intelligent individuals. Highly intelligent people often find such engagements taxing, marked by repetitive explanations, misunderstandings, and the need to simplify complex concepts. This "cessation of having to cope" is not elitism but a pragmatic response to cognitive dissonance and emotional exhaustion.

Psychological literature supports this. Studies show that intelligent individuals tend to prefer solitude or selective socialization, prioritizing quality over quantity in relationships. This stems from the frustration of mismatched discourse, where the intelligent must constantly "mind" others' limitations, leading to burnout. For instance, profoundly gifted individuals report feelings of alienation in average settings, as their rapid processing & abstract thinking clash with slower-paced interactions. Research on social evaluations further reveals that while intelligence positively correlates with being liked, highly intelligent people may like others less, reflecting the asymmetry in relational dynamics.

This burden is exacerbated by the Dunning-Kruger effect, where less competent individuals, unaware of their deficits, demand equal footing in discussions, leading to unproductive conflicts. Intelligent people, cognizant of these dynamics, seek respite in superior company, where conversations flow efficiently and enrichingly. Persuasively, this choice optimizes mental resources, allowing focus on high-level pursuits rather than remedial education of others.

Evidence from Diverse Fields: A Scholarly Synthesis

To bolster this argument, consider interdisciplinary evidence. In evolutionary psychology, intelligence is linked to prosocial behaviors, but selectively so; smarter individuals gravitate toward peers who match or exceed their level to maximize adaptive advantages like knowledge acquisition. Economic models of human capital similarly predict that high-ability agents cluster together, as seen in elite institutions like MIT or Silicon Valley hubs, where being "dumbest" is the norm for entrants.

Contemporary examples abound. Tech entrepreneurs like Elon Musk surround themselves with top engineers, not to overshadow them but to leverage their expertise. Psychological surveys confirm that high-IQ societies, such as Mensa, often report dissatisfaction in mixed-ability groups, preferring forums where they can learn. These patterns persuasively demonstrate that the pursuit of being the least knowledgeable is a hallmark of true intelligence, driven by empirical benefits rather than ego.

Conclusion: Embracing the Pursuit of Intellectual Inferiority

In summation, the notion that smart people crave dominance is a fallacy perpetuated by the cognitive biases of the less intelligent, as illuminated by the Dunning-Kruger effect and related research. Instead, truly intelligent individuals seek to be the "dumbest in the room" for the dual rewards of boundless learning & liberation from intellectual drudgery. This behavior is supported by psychological studies, historical precedents, and logical imperatives, forming a compelling case for its adoption by truly gifted individuals; but those most apt to benefit are also most likely to have already adopted it naturally.