The Necessity of Labor for Wealth: A Philosophical Inquiry

Summary: From the earliest stirrings of human civilization to the complexities of modern economies, labor has been unequivocally recognized as the fundamental bedrock upon which wealth is built. This pillar page delves into the philosophical arguments, spanning centuries of thought within the Great Books of the Western World, that establish the necessity of labor not merely for individual survival, but for the creation, accumulation, and distribution of societal wealth. We will explore how philosophers have grappled with the definition of labor and wealth, the role of the State in their intersection, and the interplay between necessity and contingency in the grand tapestry of human economic endeavor.

Setting the Stage: Labor, Value, and Human Endeavor

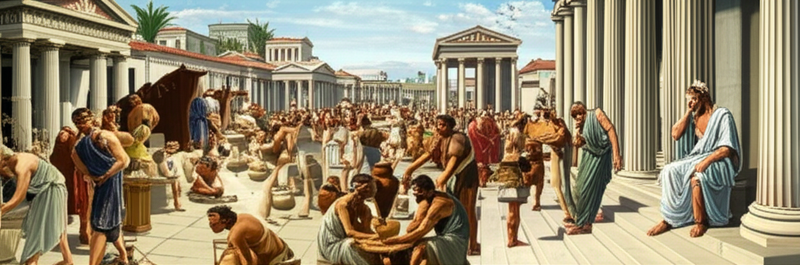

The question of how wealth is created is not merely an economic one; it is profoundly philosophical. Before coins or markets, before complex legal systems or global trade, humans labored to survive. They tilled the soil, hunted, gathered, and crafted tools. This primal act of engagement with the natural world, transforming it to meet needs, forms the genesis of wealth. Philosophers, from Plato to Marx, have meticulously examined this relationship, seeking to understand its inherent nature and its implications for justice, society, and the human condition.

Our exploration will trace the intellectual lineage that posits labor as the indispensable engine of prosperity, distinguishing between the necessity of effort and the contingent factors that shape its outcomes and distribution.

The Philosophical Roots of Labor's Necessity

The idea that labor is essential for wealth is not a modern innovation but a thread woven deeply into the fabric of Western thought.

Early Perspectives: From Survival to Civilization

Ancient Greek philosophers, while often viewing manual labor as a pursuit for the lower classes or slaves, implicitly acknowledged its necessity for the sustenance of the polis and the leisure of its citizens.

- Plato's Republic: Envisions a city where individuals specialize in tasks – farmers, artisans, soldiers, guardians – each contributing their labor to the collective good. The necessity of these various forms of work ensures the city's self-sufficiency and stability. Without the labor of the farmers, there is no food; without the artisans, no tools or shelter.

- Aristotle's Politics: Differentiates between natural and unnatural acquisition of wealth. Natural acquisition involves household management (oikonomia), focused on acquiring necessities through labor – farming, hunting, fishing. This form of wealth is limited by need. Unnatural acquisition, like pure money-making, is seen as potentially limitless and less noble, but even here, some form of labor or ingenuity is involved in its pursuit.

For the ancients, the labor of many was a necessity for the wealth (in terms of resources and stability) of the State and the flourishing of its elite.

Labor as the Source of Value: Locke's Proviso

Perhaps no philosopher articulated the link between labor and property (and thus, wealth) more powerfully than John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government.

Locke argues that while God gave the world to mankind in common, individuals acquire private property through their labor. When a person mixes their labor with something from nature, they infuse it with their own essence, thereby making it their own.

- The "Labor Theory of Property":

- "Every man has a property in his own person: this nobody has any right to but himself. The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his."

- "Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property."

This concept establishes labor as the original source of value and ownership. The necessity of labor transforms common resources into usable, valuable goods, thereby creating wealth from what was previously unowned and unvalued. Locke's proviso, that one should leave "enough, and as good" for others, attempts to balance this individual appropriation with a broader societal contingency.

Wealth Beyond Mere Accumulation

The concept of wealth itself warrants philosophical scrutiny. Is it merely material possessions, or does it encompass a broader spectrum of human flourishing?

Defining Wealth: Beyond Material Possessions

While often equated with material abundance, philosophical traditions offer richer definitions of wealth.

- Material Wealth: Tangible assets, resources, and goods produced through labor. This is the most common understanding.

- Intellectual Wealth: Knowledge, skills, and cultural heritage, often accumulated through intellectual labor and passed down through generations. This contributes to a society's overall capacity for innovation and production.

- Social Wealth: Strong institutions, robust social contracts, and cooperative networks – elements that reduce the contingency of individual survival and enhance collective prosperity, often built through the labor of governance and community building.

The State plays a crucial role in safeguarding and facilitating the creation of all these forms of wealth, ensuring the conditions under which productive labor can thrive.

The Dialectic of Labor and Capital

The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution brought new perspectives on labor and wealth.

- Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations: Argued that the division of labor is the primary driver of increased productivity and, consequently, national wealth. Specialization allows for greater efficiency, leading to a surplus that can be traded and accumulated. Smith acknowledges the necessity of labor for production but also highlights the contingency of market forces and individual self-interest in directing that labor towards maximum wealth creation.

- Karl Marx's Das Kapital: While critical of capitalism's exploitative tendencies, Marx profoundly affirmed the necessity of labor as the sole source of all value. He posited that capital itself is accumulated past labor, and profit is derived from surplus value, the unpaid labor of the worker. For Marx, the State under capitalism serves to protect the interests of capital, further entrenching the necessity of labor for capitalist wealth while alienating the laborer from the fruits of their efforts.

The State, Society, and the Organization of Labor

The relationship between labor, wealth, and the State is complex and dynamic. The State is not merely a passive observer but an active shaper of the conditions under which wealth is generated and distributed.

Regulating the Means: The Role of the State

The State provides the framework that makes large-scale, productive labor possible and sustainable.

- Property Rights: By establishing and enforcing property rights, the State incentivizes labor and investment, as individuals know their efforts will lead to secure ownership and accumulation of wealth.

- Infrastructure: Public works, education systems, and legal frameworks (courts, contracts) are all forms of collective labor and investment by the State that create an environment conducive to individual and collective wealth creation.

- Social Safety Nets: While often seen as redistributive, social safety nets can also be viewed as a necessity for maintaining a healthy, productive workforce, reducing the contingency of poverty that can hinder productive labor.

Contingency in Wealth Creation: Beyond Pure Labor

While labor is undeniably necessary, the contingency of various factors determines the extent and form of wealth generated.

- Natural Resources: The availability of fertile land, minerals, or favorable climate can amplify or constrain the fruits of labor.

- Innovation and Technology: New tools and methods can dramatically increase the productivity of labor, leading to unprecedented wealth.

- Market Dynamics: Supply and demand, competition, and global trade can influence the value assigned to specific forms of labor and the wealth derived from them.

- Social and Political Stability: Peace, rule of law, and good governance reduce uncertainty and create a predictable environment for long-term investment and productive labor.

Thus, while labor is a necessity, the magnitude and distribution of wealth are profoundly contingent upon a myriad of interacting forces, many of which are shaped by the actions and policies of the State.

The Enduring Philosophical Debate

The fundamental relationship between labor and wealth continues to be a fertile ground for philosophical inquiry, adapting to new societal challenges.

Modern Challenges and Perspectives

In an age of automation and artificial intelligence, the nature of labor is evolving, prompting new questions about its necessity for wealth creation.

- Automation and UBI: If machines perform much of the traditional labor, how will wealth be generated and distributed? Concepts like Universal Basic Income (UBI) are philosophical attempts to address the potential decoupling of labor from subsistence, yet even here, the necessity of human ingenuity (a form of intellectual labor) to create and maintain these systems remains.

- The Gig Economy: The rise of flexible, often precarious labor, challenges traditional notions of employment and the State's role in protecting workers' rights and ensuring fair compensation for their labor.

The Ethics of Wealth and Labor

Beyond how wealth is created, philosophy also asks why and for whom.

- Justice in Distribution: If labor is the source of wealth, what constitutes a just distribution of that wealth? This question has animated thinkers from Rousseau to Rawls, debating the necessity of equality versus meritocracy, and the State's ethical obligations in this regard.

- The Purpose of Wealth: Is wealth an end in itself, or a means to human flourishing, intellectual development, or societal progress? This takes us back to Aristotle's distinction between wealth for sustenance versus wealth for its own sake, and the contingency of how wealth is ultimately used.

Conclusion: The Unshakeable Link: Labor as the Foundation of Prosperity

From the rudimentary acts of survival to the sophisticated complexities of global economies, the philosophical journey through the Great Books of the Western World consistently affirms the necessity of labor for the creation of wealth. Whether seen as the source of property, the engine of productivity, or the fundamental wellspring of value, human effort – physical, intellectual, and organizational – remains indispensable. While contingent factors like natural resources, technological innovation, market forces, and the policies of the State profoundly influence the scale and distribution of wealth, the act of labor itself is the irreducible starting point. To understand wealth is to understand the enduring power and philosophical significance of human endeavor.

Further Exploration

For those wishing to delve deeper into these profound philosophical questions, consider these seminal works and resources:

-

Great Books for Deeper Dive:

- Plato, The Republic (Books II-IV on the ideal city and division of labor)

- Aristotle, Politics (Book I on household management and natural acquisition)

- John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (Chapter V on Property)

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Book I on the division of labor and the origins of wealth)

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital (Volume I, Part III on the production of absolute surplus-value)

-

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

-

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "John Locke Labor Theory of Property explained"

* ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Adam Smith The Wealth of Nations summary"