The Necessity of Labor for Wealth: A Philosophical Inquiry

Summary: Unpacking the Foundation of Prosperity

From the earliest stirrings of human civilization to the complexities of modern global economies, one constant remains: labor is the indispensable crucible in which wealth is forged. This pillar page delves into the profound philosophical arguments that affirm the necessity of human effort in generating value and prosperity. We will journey through the annals of thought, from ancient Greek philosophers who first pondered the nature of economic activity, to Enlightenment thinkers who formalized the labor theory of value, and beyond. While labor’s role is necessary, the specific forms and distributions of wealth are often contingent upon societal structures, political systems, and the interventions of the State. This exploration, drawing heavily from the Great Books of the Western World, seeks to illuminate the enduring philosophical underpinnings of why, without labor, wealth in any meaningful sense simply cannot exist.

Introduction: The Sweat of Our Brows and the Fabric of Our Lives

Imagine a world without human endeavor. Without the farmer tilling the soil, the artisan shaping raw materials, the architect designing shelter, or the philosopher shaping ideas. What remains? Untouched resources, dormant potential. It is only through the transformative power of labor – the application of human physical and intellectual effort – that these raw potentials are converted into goods, services, and knowledge that constitute wealth.

This isn't merely an economic observation; it's a profound philosophical truth, a cornerstone upon which societies are built. Yet, the precise relationship between labor and wealth has been a subject of intense debate for millennia. Is labor inherently valuable? How does it create ownership? What role does the State play in mediating this relationship? And to what extent are the outcomes of labor a matter of necessity versus contingency? At planksip, we believe that grappling with these questions is essential for understanding not just our economies, but our very humanity.

The Ancient Echoes: Labor, Value, and the Good Life

Long before the advent of industrial capitalism, ancient thinkers grappled with the nature of work and its contribution to society. Their insights, though framed within different societal contexts, lay crucial groundwork.

Aristotle and the Pursuit of Eudaimonia

In his Politics and Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle distinguishes between oikonomia (household management, focused on satisfying needs) and chrematistics (the art of money-making, which he viewed with suspicion when pursued for its own sake). For Aristotle, labor was primarily a means to an end: the provision of necessities for a virtuous and flourishing life (eudaimonia). He recognized the division of labor within the household and the polis as essential for collective well-being. While he valued the intellectual and civic life above manual labor, he implicitly acknowledged the necessity of labor for the material conditions that enable higher pursuits. The wealth generated was meant to serve the community, not merely accumulate.

Plato's Republic: Specialization as a Foundation

Plato, in his Republic, outlines a highly structured society built upon the principle of specialization. Each class – guardians, auxiliaries, and producers – performs specific functions. The producers, comprising farmers, artisans, and merchants, are responsible for generating the material wealth necessary to sustain the entire polis. This division of labor, driven by individual aptitudes, is presented as a necessary condition for a harmonious and efficient society. Without the dedicated labor of each group, the ideal state could not function, demonstrating an early understanding of how coordinated effort underpins collective prosperity.

From Medieval Justifications to Enlightenment Rights: Property and Production

The medieval period, heavily influenced by scholastic thought, focused on the moral dimensions of economic activity. With the Enlightenment, the concept of individual rights and the origins of property gained prominence, profoundly shaping our understanding of labor's role.

Thomas Aquinas: Just Price and the Labor of the Artisan

Drawing on Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, discussed the concept of a "just price." While complex, it implicitly recognized the effort and resources expended in producing goods. The labor of the artisan, the merchant, and the farmer was seen as contributing value, and their compensation should reflect that contribution, preventing exploitation. This laid a moral foundation for valuing human effort.

John Locke: Labor as the Origin of Property

Perhaps no philosopher more powerfully articulated the link between labor and property than John Locke. In his Second Treatise of Government, Locke argues that an individual acquires a right to property by "mixing his labor" with natural resources. When a person cultivates land, gathers fruit, or shapes wood, their effort transforms the common into the personal.

"Every man has a property in his own person. This nobody has any right to but himself. The labor of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labor with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property."

This idea is revolutionary. It posits that labor is not just a means to acquire things, but the very source of legitimate ownership and, by extension, private wealth. This establishes labor as a fundamental necessity for property rights beyond mere possession, though the extent and limits of this right become a matter of contingency based on societal agreements and the rule of law.

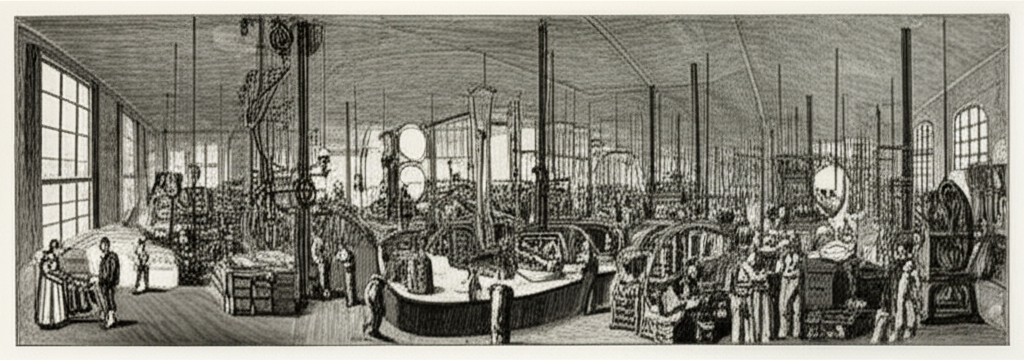

The Industrial Age: Labor as the Engine of Nations

The Enlightenment's focus on individual effort and rights paved the way for the classical economists of the 18th and 19th centuries, who placed labor squarely at the heart of economic production and value.

Adam Smith: The Wealth of Nations and the Division of Labor

Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, famously articulated the transformative power of the division of labor. His pin factory example vividly illustrates how specialization dramatically increases productivity, leading to greater output and, consequently, greater wealth for a nation.

Smith argued that labor is the "real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities." While he also considered supply and demand, the underlying cost of production, largely driven by labor, was paramount. He saw the "invisible hand" of the market coordinating individual labors for collective benefit, making labor a necessary component for a thriving commercial society.

David Ricardo and Karl Marx: The Labor Theory of Value

Building on Smith, David Ricardo further developed the labor theory of value, positing that the value of a commodity is determined by the amount of labor required for its production. This concept became a cornerstone of classical economics.

Karl Marx, deeply influenced by Ricardo, took the labor theory of value in a radical direction. In Das Kapital, Marx argued that under capitalism, labor power itself becomes a commodity. Workers sell their ability to labor, but the value they create (their surplus value) exceeds the wages they receive. This surplus value, appropriated by the capitalist, is the source of profit and capital accumulation. For Marx, labor is undeniably the source of all wealth, but its organization under capitalism leads to exploitation and alienation. This highlights how the organization and distribution of wealth, despite its necessity of origin in labor, are highly contingent upon the prevailing economic system.

The State, Society, and the Contingency of Wealth Distribution

While labor is the necessary engine of wealth, the manner in which that wealth is distributed, protected, and regulated is profoundly contingent upon the structures of the State and the prevailing social contract.

The State as Arbiter and Enabler

- Protecting Property and Contracts: The State, through its legal framework, protects the property rights established by labor (as per Locke) and enforces contracts, ensuring that the fruits of labor are secured. Without a stable legal system, the incentive to labor and accumulate wealth would diminish.

- Infrastructure and Education: State investment in infrastructure (roads, communication) and education enhances the productivity of labor, indirectly contributing to wealth creation.

- Regulation and Redistribution: The State can regulate labor conditions (wages, hours, safety) and redistribute wealth through taxation and social programs. These interventions reflect societal choices about fairness and equality, demonstrating the contingency of wealth distribution, even as its origin remains in labor. Thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in The Social Contract, explored how collective agreements shape the rights and duties of citizens, including their economic interactions.

Table: Philosophical Perspectives on Labor and Wealth

| Philosopher | Key Idea on Labor & Wealth | Necessity vs. Contingency Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| Plato/Aristotle | Labor as essential for societal needs and virtuous living. | Necessity for basic societal function; Contingency in status. |

| John Locke | Labor creates property rights and legitimate ownership. | Necessity for property; Contingency in extent/regulation. |

| Adam Smith | Division of labor increases productivity; labor as value measure. | Necessity for national wealth; Contingency in market dynamics. |

| Karl Marx | Labor is the source of all value, but exploited under capitalism. | Necessity of labor for value; Contingency of its distribution. |

Conclusion: The Enduring Truth of Human Endeavor

The journey through philosophical thought reveals an undeniable truth: labor is not merely a component of wealth; it is its very genesis. From the ancient farmer tilling the soil to the modern coder crafting software, human effort transforms raw potential into tangible and intangible value. This is the bedrock necessity of wealth.

However, the specific forms of wealth, its distribution, the rights associated with it, and the societal structures that govern its creation are profoundly contingent. They are shaped by the laws of the State, the prevailing economic theories, cultural norms, and the ongoing ethical debates about justice and equity. The Great Books of the Western World offer a rich tapestry of perspectives, reminding us that while the act of labor is fundamental, its meaning and consequences are constantly being redefined by human thought and societal evolution.

At planksip, we encourage you to continue this inquiry. To question not just how wealth is created, but why we value it, who benefits from it, and what kind of society we wish to build upon the foundation of our collective labor.

Further Exploration:

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Adam Smith Division of Labor Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "John Locke Labor Theory of Property"