The Indispensable Gears: Labor's Necessity for the State

Summary: The relationship between labor and the State is often viewed through an economic lens, focusing on productivity and growth. However, a deeper philosophical inquiry reveals that labor is not merely a contingent factor influencing the State's prosperity but an absolute necessity for its very existence, sustenance, and evolution. From the foundational acts of self-preservation to the complex division of tasks that define modern Government, the collective effort of human labor underpins the State's structure, functions, and capacity to secure the common good. Without it, the State, as we understand it, simply cannot be.

I. The Foundational Stones: Labor as the State's Genesis

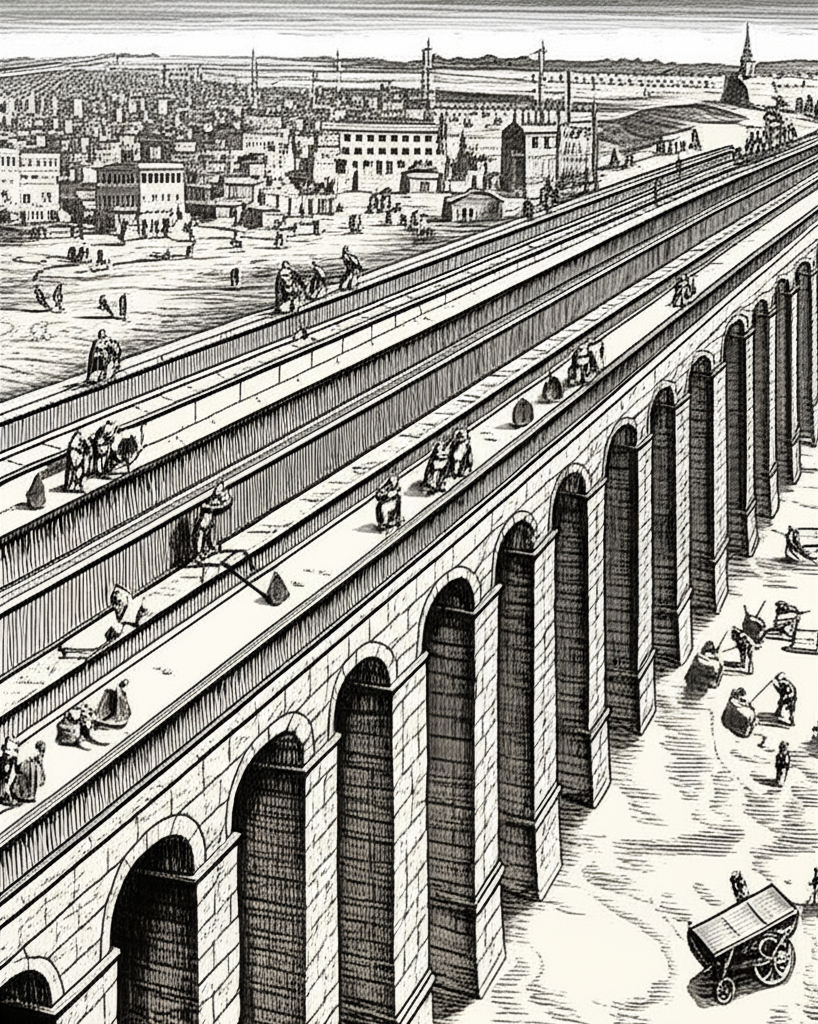

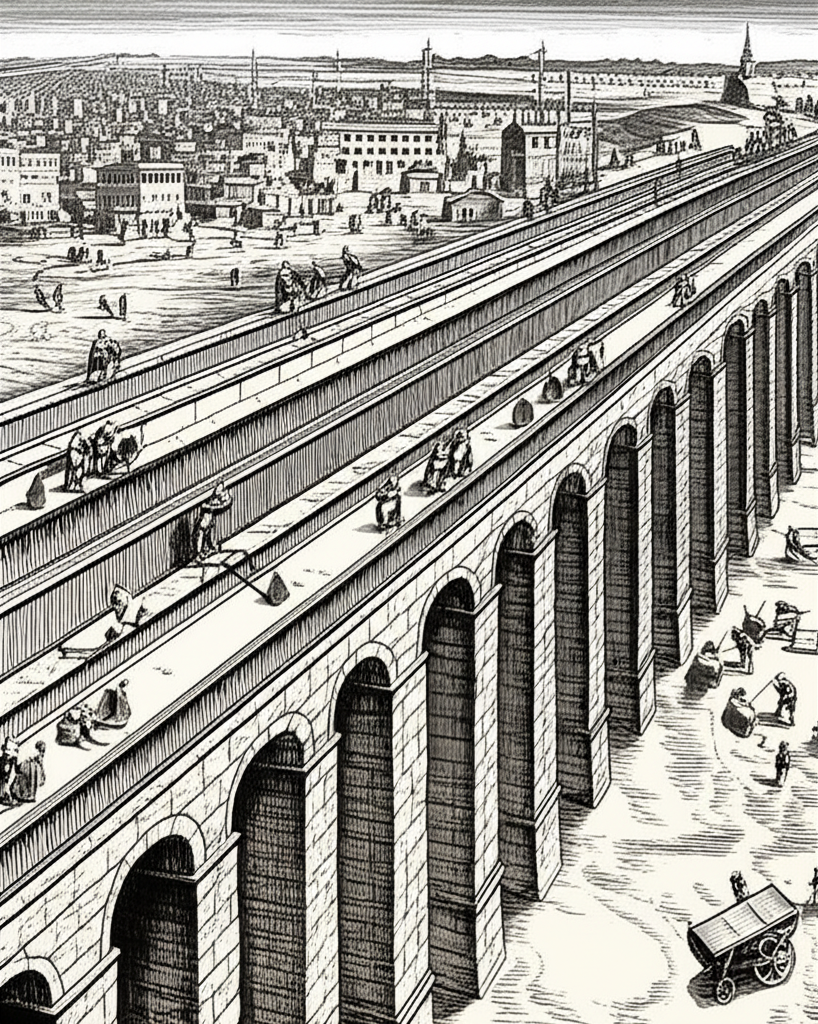

The genesis of any organized society, and by extension the State, is inextricably linked to human labor. Before the intricate frameworks of law and governance, there was the fundamental human act of working to survive, to transform nature, and to create the conditions for a stable existence.

From Primitive Needs to Organized Society

Philosophers like John Locke, in his Second Treatise of Government, posited that property, and thus the initial basis for societal organization, originates from labor. When an individual "mixes his Labour with" something from the common stock of nature, he makes it his own. This act of appropriation through labor is the first step towards establishing resources, settling, and eventually forming communities that require governance.

Similarly, Aristotle, in Politics, traces the development of the polis (State) from the household, to the village, and finally to the self-sufficient city-state. Each stage is characterized by an increasing division of labor and specialization, driven by the collective need to fulfill basic necessities more efficiently and to achieve a "good life" beyond mere survival. The necessity of cooperative labor for collective well-being is the bedrock upon which the State is built.

The Social Contract and Productive Citizens

The concept of the social contract, explored by thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and again Locke, often focuses on individuals surrendering certain rights for security and order. Yet, implicit in this contract is the understanding that this security allows for productive labor. What good is a secure State if its citizens cannot cultivate, build, or create? The Government is instituted not just to prevent chaos, but to create the stable environment where human ingenuity and labor can flourish, generating the resources and infrastructure that define a functioning society. A populace capable of labor is, therefore, a prerequisite for a viable social contract and the formation of a legitimate State.

II. Sustaining the Apparatus: Labor as Ongoing Maintenance

Once established, the State is not a static entity; it is a dynamic organism requiring constant nourishment and upkeep. This ongoing maintenance is overwhelmingly provided by the continuous labor of its citizens.

Economic Metabolism: Fueling the State's Functions

Consider the basic functions of any Government: defense, justice, infrastructure, education, healthcare. All these require resources – material, financial, and human. These resources are not conjured from thin air; they are the direct product of labor. Taxes, which fund public services, are ultimately levied on the fruits of labor and enterprise. Roads, bridges, schools, and hospitals are built and maintained by the labor of engineers, construction workers, and service providers. The very bureaucracy that administers the State is itself a form of specialized labor.

Without a continuous flow of productive labor, the State's economic metabolism grinds to a halt. Its capacity to provide for its citizens, enforce its laws, or defend its borders diminishes, leading to instability and potential collapse. The necessity of labor here is not merely for growth, but for the fundamental operational capacity of the State.

The Division of Labor and Societal Cohesion

Plato, in his Republic, famously outlined a highly specialized division of labor as essential for a just and efficient State. Farmers, artisans, soldiers, and philosopher-kings each perform specific roles, contributing their unique labor to the collective good. This division, while hierarchical, ensures that all necessary tasks are performed, and that the State can achieve self-sufficiency and internal harmony.

This concept extends beyond Plato's ideal. The complex interdependence fostered by the division of labor creates a social fabric that binds individuals to the State. Each person's labor contributes to a larger whole, making them an integral part of the collective enterprise. This fosters a sense of shared purpose and mutual reliance, reinforcing the cohesion necessary for the Government to effectively govern and for the State to endure.

III. Beyond Survival: Labor, Progress, and the Human Condition

The necessity of labor for the State transcends mere survival and maintenance; it extends to the very idea of progress, cultural development, and the flourishing of the human spirit within a societal framework.

Labor as a Formative Force for the Citizen

While often associated with drudgery, labor can also be seen as a fundamental aspect of human self-realization. Karl Marx, despite his critiques of alienated labor under capitalism, recognized labor as humanity's "species-being" – the activity through which humans transform the world and, in doing so, transform themselves. Productive, meaningful labor allows individuals to express their creativity, develop skills, and contribute tangibly to their community.

A State that facilitates conditions for meaningful labor not only benefits from the output but also cultivates more engaged, skilled, and fulfilled citizens. The necessity of providing opportunities for such labor becomes a moral imperative for a Government seeking to foster a thriving populace, which in turn contributes to a more stable and progressive State.

The Dialectic of Necessity and Contingency

It is crucial to distinguish between the absolute necessity of labor for the State and the contingency of its specific forms. The types of jobs, the economic systems (feudalism, capitalism, socialism), and the organization of labor are all contingent – they vary across time and place. However, the underlying truth remains: some form of human effort, directed towards production and maintenance, is necessary for any organized society to exist.

This interplay of necessity and contingency highlights that while the Government may choose how to organize labor, it cannot choose to eliminate it. The State is perpetually reliant on the physical and intellectual efforts of its people. Ignoring this fundamental necessity in policy-making, or treating labor as an infinite, exploitable resource, inevitably leads to societal breakdown.

IV. The Perils of Unacknowledged Labor

The historical trajectory of states is replete with examples where the neglect or exploitation of labor has led to profound instability and revolution.

When Labor's Value is Undermined

When the vital necessity of labor is ignored, or when the fruits of labor are unjustly distributed, the social contract strains. From ancient slave societies to the industrial revolutions, the struggle for fair recognition of labor has been a constant theme. A Government that fails to ensure a reasonable standard of living for its workers, or that allows for extreme exploitation, risks internal dissent, economic stagnation, and ultimately, its own legitimacy and survival.

- Social Unrest: Widespread dissatisfaction among the working populace can lead to protests, strikes, and revolutionary movements, directly challenging the authority and stability of the State.

- Economic Collapse: A demotivated, underpaid, or unhealthy workforce is unproductive. This decline in labor output cripples the economy, reducing tax revenues and the State's capacity to provide essential services.

- Brain Drain: Highly skilled labor, if undervalued, may seek opportunities elsewhere, further weakening the State's productive and innovative capacity.

The well-being of the State is thus intrinsically tied to the well-being of its laborers, making the recognition and fair treatment of labor not just an ethical concern, but a matter of political necessity.

Conclusion

The philosophical journey through the Great Books of the Western World consistently reveals labor as an undeniable and absolute necessity for the State. It is the raw material, the engine, and the very glue that binds society together. From the initial acts of transforming nature to the complex division of tasks that sustain modern Government, human effort is the indispensable force. While the contingent forms and conditions of labor may shift, its fundamental necessity for the State's genesis, survival, and progress remains an immutable truth. To understand the State is, therefore, to understand its profound and unending reliance on the collective and individual labor of its people.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "John Locke Labor Theory of Property explained"

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Republic Division of Labor and Justice"