The Shifting Sands of Belief: Unpacking the Nature of True Opinion (Doxa)

In the relentless pursuit of understanding, philosophy often compels us to scrutinize concepts we take for granted. Opinion, a seemingly mundane aspect of daily discourse, reveals a profound philosophical depth when viewed through the lens of ancient thought. This article delves into doxa, the Greek term for opinion or belief, exploring its intricate relationship with truth and knowledge. Drawing heavily from the foundational texts within the Great Books of the Western World, particularly the works of Plato, we will navigate the nuanced terrain where a belief can be correct without being fully understood, and how our sense experiences shape these often-ephemeral convictions. Understanding doxa is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for discerning the quality of our own convictions and those of the world around us.

The Everyday and the Esoteric: Defining Doxa

At its simplest, an opinion is a belief or judgment not necessarily based on fact or knowledge. We express opinions constantly – about the weather, politics, art, or the best way to brew coffee. Yet, in philosophy, particularly within the classical Greek tradition, doxa carries a weightier, more critical connotation. It represents the realm of common belief, popular judgment, or even mere appearance, often contrasted with the more rigorous and stable domain of episteme, or true knowledge. While an opinion might happen to be correct, its correctness often lacks the deep justification and understanding that elevates it to the status of knowledge.

Plato's Enduring Legacy: Doxa vs. Episteme

No philosopher elucidated the distinction between doxa and episteme more thoroughly than Plato. For Plato, as explored in dialogues such as the Republic and the Meno, doxa occupies an intermediary position between sheer ignorance and genuine knowledge. It is connected to the sensible world, the world of flux and change perceived through our senses, making it inherently less stable and reliable than episteme, which grasps the immutable Forms.

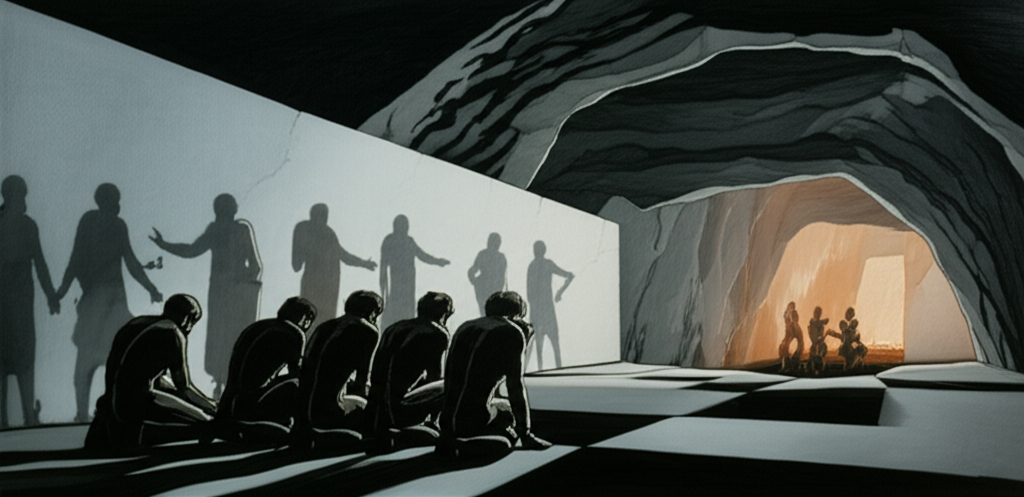

Consider the famous Allegory of the Cave from the Republic. The prisoners, chained and facing shadows, form their opinions based solely on these fleeting images. Their beliefs are real to them, but they are far from the truth of the objects casting the shadows, let alone the sun outside the cave.

However, Plato also recognized the existence of true opinion. In the Meno, Socrates famously discusses how a person can have a correct opinion about the road to Larissa without ever having traveled it or knowing the reasons why that road leads there. This true opinion is useful – it points in the right direction – but it is not knowledge because it lacks the "reasons why."

Here's a simplified distinction:

| Feature | Doxa (Opinion) | Episteme (Knowledge) |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Sense experience, popular belief, persuasion | Reason, understanding of Forms, logical deduction |

| Stability | Changeable, fleeting, persuadable | Stable, permanent, unshakeable |

| Justification | Lacks firm grounding or "reasons why" | Thoroughly justified, understood, and defended |

| Source | The sensible world, appearances | The intelligible world, Forms |

| Reliability | Can be true by chance, but unreliable | Always true, self-validating |

The Role of Sense Experience in Forming Opinion

Our senses are the primary gateways through which we interact with the world, and thus, they are fundamental to the formation of doxa. What we see, hear, touch, taste, and smell informs our perceptions, which in turn give rise to our beliefs and judgments. However, as empiricist philosophers later emphasized, and as Plato implicitly understood, sense experience is inherently subjective and often misleading.

The same object can appear differently under varying conditions or to different observers. A stick submerged in water appears bent, though it is straight. A distant mountain looks small. These sensory inputs, while real, can lead to opinions that are not aligned with the objective truth of the matter. Therefore, opinions derived solely from sense experience, without critical reflection or rational justification, remain vulnerable to error and change.

The Precarious Link: True Opinion and Truth

The concept of true opinion is perhaps the most fascinating aspect of doxa. It represents a belief that happens to align with reality, a correct answer arrived at without full comprehension of why it is correct. It's like guessing the right answer on a test without understanding the underlying principles. The truth is present in the opinion, but the knowledge of that truth is absent.

Plato's analogy in the Meno of the path to Larissa is illustrative: one can give correct directions to Larissa simply by having been told, or by a lucky guess. The directions are true, and holding them is a true opinion. However, someone who knows the way understands the geography, the landmarks, and the reasons why that particular route is correct. Their knowledge is stable and can be defended, whereas the person with mere true opinion might be easily persuaded otherwise or unable to guide others if conditions change.

From True Opinion to Knowledge: The Chains of Reason

The philosophical quest, then, is often to transform true opinion into knowledge. For Plato, this transformation occurs when one "ties down" the correct belief with reasoned argument and understanding of its causes. It is through dialectic, questioning, and the rigorous application of reason that an opinion gains stability and becomes episteme.

This process involves:

- Justification: Providing logical reasons and evidence for the belief.

- Understanding: Grasping the underlying principles and connections that make the belief true.

- Coherence: Integrating the belief within a broader system of consistent truths.

- Immutability: Recognizing that the belief is not subject to change based on subjective sense perception or persuasion.

This elevation from doxa to episteme is not a passive reception of information but an active, intellectual endeavor, moving beyond the superficiality of appearances to the bedrock of rational insight.

The Value of Cultivating True Opinion

While doxa is often presented as inferior to episteme, it is far from useless. In practical life, having true opinions is immensely valuable. A physician with true opinions about a diagnosis, even if they can't fully articulate the biochemical mechanisms, can still save a life. A leader with true opinions about policy can guide a nation effectively.

The danger lies not in having opinions, but in mistaking them for knowledge, or in being swayed by false opinions that lead to detrimental outcomes. Cultivating the ability to discern opinions that are likely to be true, and critically examining the foundations of all our beliefs, is a crucial step towards wisdom. It encourages intellectual humility and the ongoing pursuit of deeper understanding.

Conclusion: Doxa as a Stepping Stone

The nature of true opinion, or doxa, stands as a testament to the complexities of human cognition and our perennial quest for truth. Far from being a mere dismissal of popular belief, Plato's exploration of doxa highlights a critical stage in our intellectual journey. It underscores the distinction between merely being right and truly knowing why one is right. Our senses provide the raw material, and our initial opinions form the first interpretations. The challenge, and the enduring philosophical task, is to move beyond these often-unjustified beliefs, to tether our true opinions with the chains of reason, and ascend towards the more stable, defensible realm of knowledge. Doxa, therefore, is not an endpoint, but a crucial, often illuminating, stepping stone on the path to genuine understanding.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Meno True Opinion Knowledge Explained"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Allegory of the Cave Explained Philosophy"