The Nature of True Opinion (Doxa): Navigating the Labyrinth of Belief

Summary: In the grand tapestry of human thought, opinion (doxa) occupies a peculiar and often misunderstood position. While distinct from knowledge (episteme) and truth (aletheia), a "true opinion" presents a fascinating philosophical paradox: it is a belief that happens to align with reality, yet lacks the secure grounding or justification that elevates it to the status of knowledge. This exploration delves into the classical understanding of doxa, particularly through the lens of the Great Books of the Western World, dissecting its relationship with truth and knowledge, and examining how our sense experiences shape these often-fragile convictions.

Unpacking Doxa: More Than Just a Hunch

From the bustling agora of ancient Athens to the digital echo chambers of today, opinion has always been a fundamental currency of human interaction. But what exactly constitutes an opinion, especially one deemed "true"?

In classical Greek philosophy, particularly with Plato, doxa (δοξα) referred to common belief, popular opinion, or mere appearance. It stood in stark contrast to episteme, which signified genuine, justified, and infallible knowledge. The challenge, however, arises when an opinion, formed perhaps by intuition or simple observation through our senses, happens to be correct. It's like guessing the exact number of marbles in a jar without actually counting them – you might be right, but you don't know you're right in the same way someone who counted does.

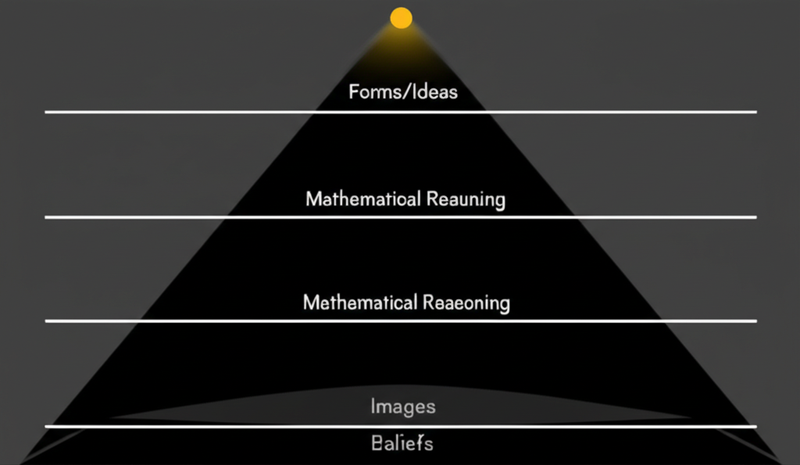

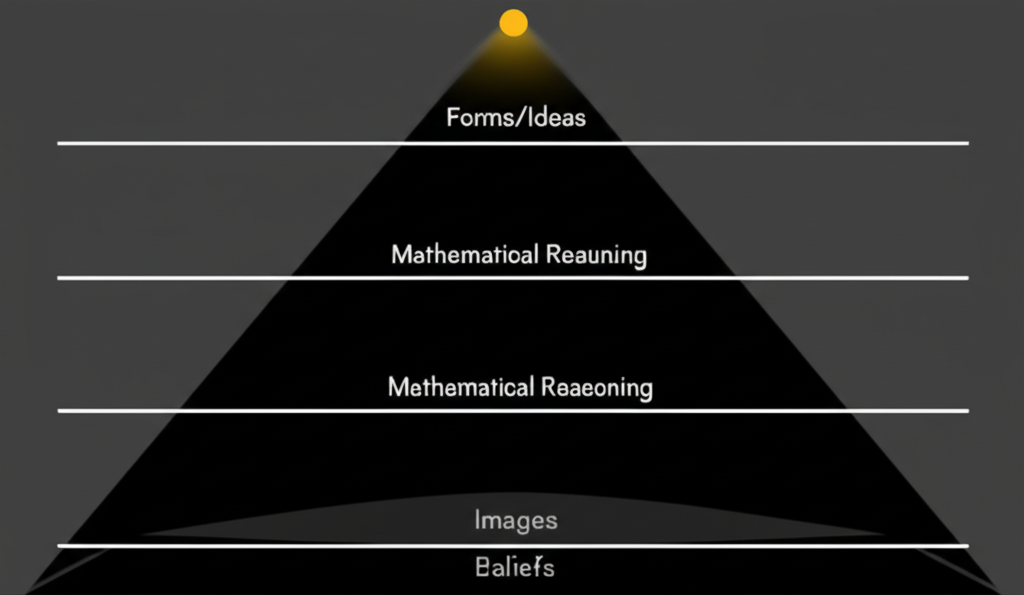

Plato, in his Republic, famously illustrates this distinction with the Allegory of the Cave and the Divided Line. The shadows on the cave wall represent the realm of doxa – fleeting perceptions and unsubstantiated beliefs. The journey out of the cave, towards the sun, symbolizes the ascent to knowledge and ultimately, the apprehension of Truth. For Plato, true opinion, while hitting the mark, is still tethered to the sensible world and lacks the firm, rational grounding of episteme. It's a stepping stone, perhaps, but not the destination.

The Elusive Quest for Truth in Opinion

The question that perpetually nags at the philosophical mind is: How can an opinion be true without being knowledge? This isn't just an academic quibble; it cuts to the heart of how we understand our beliefs and make decisions.

Consider a doctor who, based on a gut feeling (an opinion formed through years of sense experience but lacking a specific diagnostic test), correctly diagnoses a rare condition. The diagnosis is true, but without the objective evidence or repeatable methodology, it remains, strictly speaking, a true opinion rather than verifiable knowledge. The doctor got it right, but perhaps couldn't articulate why with absolute certainty beyond "it just felt like it."

Our senses play a crucial role in forming these opinions. We see, hear, touch, taste, and smell, and from these raw data points, we construct our understanding of the world. These perceptions, however, are subjective and often incomplete. An opinion born of sense experience can be accurate without being deeply understood or universally justifiable. It's the difference between seeing that it's raining (a true opinion based on sense) and understanding the meteorological principles behind precipitation (knowledge).

Opinion, True Opinion, and Knowledge: A Philosophical Triangulation

To further clarify these distinctions, let's delineate the key characteristics:

| Category | Description

This table highlights a crucial point: truth alone is not sufficient to constitute knowledge. A true opinion is accurate, but its truthfulness is often a happy accident, lacking a clear, articulable, and verifiable justification.

The Problem of Justification

The difficulty lies in the justification of the belief. If you truly know something, you can generally explain why it's true, provide evidence, or demonstrate its validity. With a true opinion, the "why" is often absent or insufficient. This is why Plato, through Socrates, emphasized the relentless questioning of assumptions and beliefs – to test if they truly stood on the bedrock of reason or the shifting sands of mere opinion.

The Perils and Potentials of Doxa

The nature of true opinion, while intellectually intriguing, also carries significant practical implications for individuals and society.

Perils of Unexamined Opinion

- Dogmatism: When individuals mistake a true opinion for knowledge, they can become rigid in their beliefs, unwilling to consider alternative perspectives or evidence. This stifles intellectual growth and critical discourse.

- Vulnerability to Manipulation: Opinions, especially those without strong justification, can be easily swayed by rhetoric, propaganda, or charismatic figures. History is replete with examples of societies led astray by compelling, yet ultimately unfounded, opinions.

- Lack of Actionable Insight: While a true opinion might identify a problem, it often fails to provide the deeper understanding needed to formulate effective solutions. Knowing that a bridge is weak is different from knowing why it is weak and how to repair it.

Potentials of Informed Opinion

- Catalyst for Inquiry: A true opinion can be the starting point for a deeper investigation. "I believe this is true, but why?" – this question drives scientific discovery and philosophical exploration.

- Practical Decision-Making: In everyday life, we often don't have the luxury of absolute knowledge. True opinions, even if not fully justified, are essential for navigating daily choices and making good enough decisions.

- Social Cohesion: Shared opinions, even if not rigorously proven, can form the basis of collective action, cultural norms, and community identity. The challenge is to ensure these shared opinions are open to critical examination.

Daniel Sanderson's Take: The Perennial Human Predicament

Here at planksip, we're constantly grappling with these distinctions. The perennial human predicament is precisely this: we are creatures of opinion, yet we yearn for truth and knowledge. The digital age, with its explosion of information and opinion, only amplifies this challenge. Everyone has a platform, and every belief, justified or not, can find an audience.

The crucial lesson from the Great Books is not to dismiss opinion entirely, but to understand its nature. To recognize that a belief can be true without being knowledge is an act of intellectual humility. It demands that we constantly question our own assumptions, seek justification for our convictions, and remain open to the possibility that what we hold as fact might merely be a fortunate guess. The pursuit of truth is not about accumulating opinions, but about rigorously testing them, refining them, and, where possible, elevating them to the robust certainty of knowledge. This journey, powered by critical thought and an unwavering commitment to reason, is what planksip is all about.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Doxa

The nature of true opinion remains a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry, challenging us to reflect on the very foundations of our beliefs. While we may never fully escape the realm of doxa, understanding its limitations and its potential is vital. By striving for justification, embracing critical self-reflection, and constantly seeking deeper understanding beyond mere sense perception, we move closer to the elusive ideal of genuine knowledge and a more profound grasp of truth.

Further Exploration

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Allegory of the Cave Explained"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "What is Epistemology? Knowledge vs. Opinion"