The Elusive Nature of True Opinion (Doxa)

In the grand tapestry of philosophical inquiry, few concepts are as foundational, yet as persistently perplexing, as doxa – opinion. Specifically, we're drawn to the question of true opinion. What does it mean for an opinion to be true, and how does such a state relate to the more exalted realm of knowledge? This article delves into the philosophical exploration of true opinion, primarily through the lens of classical thought, examining its characteristics, its origins in sense perception, and its critical distinction from genuine knowledge. We seek to understand why, even when an opinion happens to align with truth, it often falls short of the rigorous demands of philosophical certainty.

Unpacking Doxa: Opinion in the Ancient World

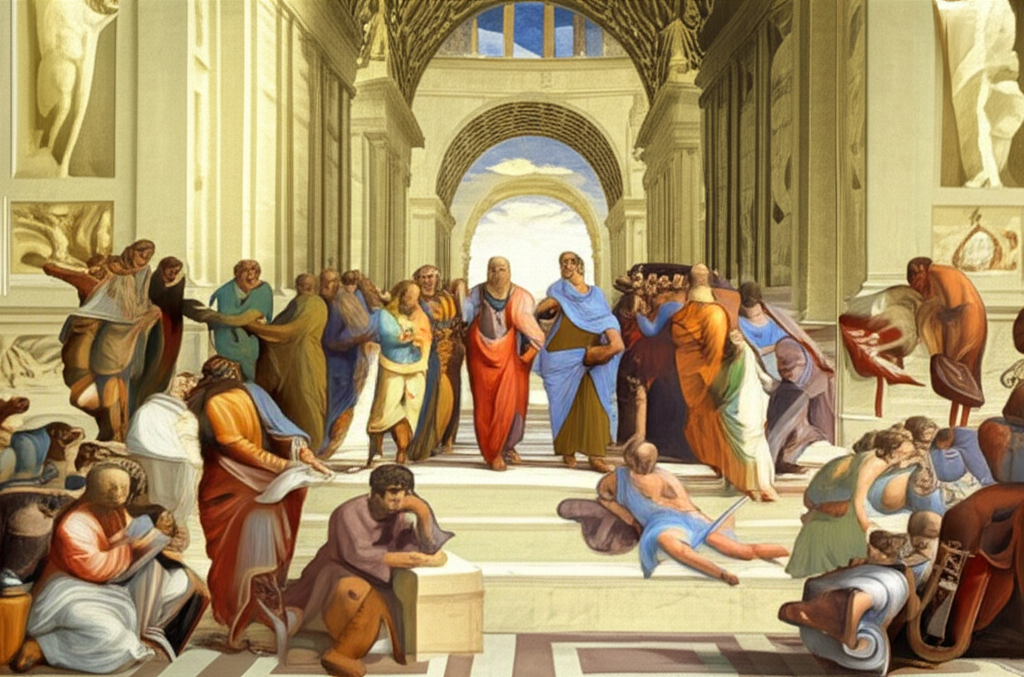

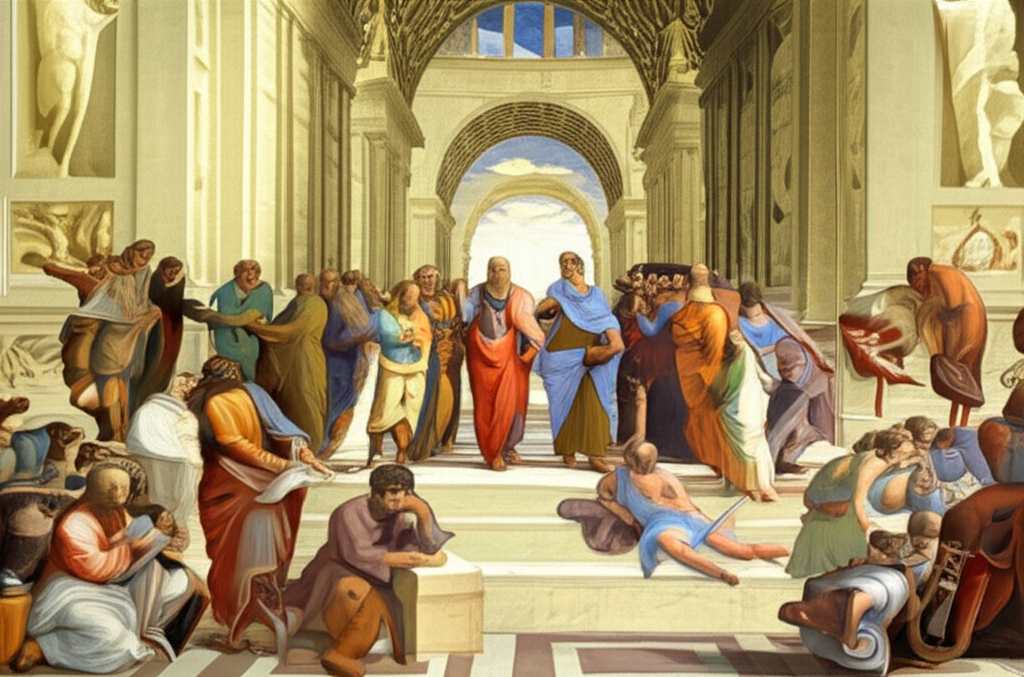

The term doxa originates from ancient Greek and broadly translates to "opinion," "belief," or "common report." It stands in stark contrast to episteme, which signifies "knowledge" or "understanding." For thinkers like Plato, whose dialogues form a cornerstone of the Great Books of the Western World, this distinction was paramount. Doxa was often associated with the fleeting, the changeable, and the world perceived through our senses – a world of appearances. Episteme, on the other hand, pertained to the immutable, the eternal Forms, accessible only through intellect and rigorous dialectic.

Consider Plato's Meno, where Socrates famously grapples with the concept. He illustrates that even a slave boy, through careful questioning, can arrive at a true geometric proposition. Yet, Socrates distinguishes this "true opinion" from knowledge, arguing that true opinions are "not inclined to stay long, but run away out of the human soul." They are like the statues of Daedalus, beautiful and lifelike, but prone to wandering off unless "tied down" by an account of the reason why.

The Role of Sense Perception in Forming Opinion

Our immediate experience of the world is overwhelmingly mediated by our senses. We see, hear, touch, taste, and smell, forming countless impressions that coalesce into our opinions. If the sky is blue, we form the opinion that "the sky is blue." If a fruit tastes sweet, we opine that "this fruit is sweet." These are often true opinions, directly reflective of our sense data.

However, the reliability of sense perception is a perennial philosophical problem. Our senses can deceive us. A stick half-submerged in water appears bent, though it is straight. A distant object may look small, though it is large. Thus, opinions formed solely on the basis of sense data, while sometimes true, lack the robustness and universality required for knowledge. They are contingent on the observer's position, the conditions of observation, and the inherent limitations of our biological apparatus.

True Opinion vs. Knowledge: A Critical Distinction

The crucial difference between true opinion and knowledge lies not in their factual accuracy, but in their justification and stability.

| Feature | True Opinion (Doxa Orthē) | Knowledge (Episteme) |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | May be true; aligns with reality. | Is true; necessarily aligns with reality. |

| Justification | Lacks a full, reasoned account of why it is true; often based on intuition, experience, or hearsay. | Possesses a coherent, logical, and demonstrable account of why it is true. |

| Stability | Unstable; prone to change, forgetfulness, or being swayed by argument. | Stable; firmly "tied down" by understanding, resistant to superficial challenge. |

| Origin | Often derived from sense perception, convention, or accidental discovery. | Derived from rational insight, rigorous inquiry, and understanding of underlying causes. |

| Reliability | Fortuitous; correct by chance or good fortune. | Systematic; correct through reasoned necessity. |

Plato, in the Republic, famously likens true opinion to being guided by someone who knows the way but cannot explain how they know it. They get you to the destination, but without understanding the route, you might get lost on the return journey or be unable to guide others. Knowledge, conversely, involves not just reaching the destination, but understanding the entire map, the terrain, and the principles of navigation.

The Value and Limitations of True Opinion

Despite its shortcomings when compared to knowledge, true opinion is not without value. Indeed, much of our daily lives, and even significant historical progress, relies on it. A skilled artisan, a seasoned politician, or a brilliant general may operate effectively on the basis of true opinions derived from vast experience, intuition, and acute sense perception, even if they cannot articulate the underlying principles with philosophical rigor. Their actions are true in their efficacy.

However, the limitation is evident: without knowledge, without understanding why an opinion is true, it remains vulnerable. It cannot be reliably taught, consistently replicated, or definitively defended against sophisticated counter-arguments. It lacks the deep explanatory power that defines true knowledge.

Conclusion: The Pursuit Beyond Mere Truth

The exploration of "The Nature of True Opinion (Doxa)" reveals a fundamental philosophical challenge: the distinction between merely being right and understanding why one is right. While true opinions, often rooted in our sense experience, can guide us effectively in many circumstances, they ultimately point towards a higher aspiration. The journey from doxa to episteme is the very heart of philosophy – a relentless pursuit not just of truth, but of reasoned justification, stable understanding, and genuine knowledge. It's a journey that demands we tie down our fleeting truths with the chains of logos, transforming fortunate guesses into enduring insights.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Meno True Opinion Knowledge"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Epistemology Doxa Episteme Distinction"