The Enduring Enigma: Deconstructing the Nature of Art and Form

The philosophical inquiry into Art and Form is as ancient as philosophy itself, tracing its origins through the foundational texts of Western thought. This article delves into how philosophers, from Plato to Kant and beyond, have grappled with these concepts, exploring their intricate relationship to Beauty and Quality, and revealing art not merely as decoration, but as a profound lens through which we understand reality, ourselves, and the very structure of existence. We will see that the form of an artwork is not just its external shape, but its essential organizing principle, inextricably linked to its aesthetic impact and enduring value.

I. The Ancient Foundations: Form as Ideal and Structure

The journey into the nature of art and form begins with the towering figures of ancient Greece, whose insights laid the groundwork for millennia of aesthetic discourse.

A. Plato's Realm of Forms: Art as Imitation

For Plato, as articulated in works like The Republic, Form exists in a transcendent, perfect realm – the World of Forms. Everything we perceive in the material world is merely a shadow or an imperfect imitation of these eternal Forms. Art, then, becomes an imitation of an imitation. A painter depicting a bed is imitating a specific bed, which itself is an imperfect copy of the ideal, eternal Form of "Bed."

- Art's Dilemma: This perspective casts art in a somewhat suspicious light. It is twice removed from truth, potentially misleading, and appealing to emotions rather than reason.

- The Form of Beauty: Yet, Plato also posited the Form of Beauty itself – an ultimate, pure, and unchanging essence that all beautiful things imperfectly partake in. True Beauty is not found in a specific object, but in the apprehension of this ideal Form.

B. Aristotle's Empirical Approach: Form as Inner Principle

Aristotle, Plato's student, offered a more immanent view of Form, particularly in his Poetics. While still recognizing art as mimesis (imitation), he saw it not as a mere copying of superficial appearances, but as an imitation of actions and human nature, revealing universal truths.

For Aristotle, Form is not separate from matter but is inherent within it, giving a thing its structure, purpose, and identity. In art, the artist imposes form upon raw material, shaping it towards a specific end.

- The Four Causes: Aristotle's framework of causality is illuminating:

- Material Cause: What something is made of (e.g., marble for a statue).

- Formal Cause: The essence or design (the idea of the statue in the sculptor's mind).

- Efficient Cause: The agent that brings it about (the sculptor).

- Final Cause: The purpose or end (the statue's intended effect or meaning).

This understanding elevates the artist's role, seeing them as revealing the potential form within the material, making the invisible visible, and creating coherent, purposeful structures.

II. The Evolution of Beauty and Aesthetic Judgment

As Western thought progressed, the understanding of Beauty shifted from an objective, Platonic ideal to a more complex, often subjective, experience.

A. From Objective Ideal to Subjective Experience

| Philosophical Era | View of Beauty | Key Thinkers (Great Books) |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greece | Objective, inherent in the Form, proportion, harmony. | Plato, Aristotle |

| Medieval Period | Reflects divine order, spiritual truth, God's perfection. | Augustine, Aquinas |

| Enlightenment/Modern | Subjective, a judgment of taste, universalizable feeling. | Kant, Hume |

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment, profoundly reshaped aesthetic theory. He argued that judgments of Beauty are subjective, arising from a disinterested pleasure, yet they carry a peculiar demand for universal assent. When we call something beautiful, we expect others to agree, not based on a concept, but on a shared human capacity for aesthetic feeling. For Kant, the apprehension of form (purposiveness without purpose) is central to this experience.

III. Form as the Crucible of Quality

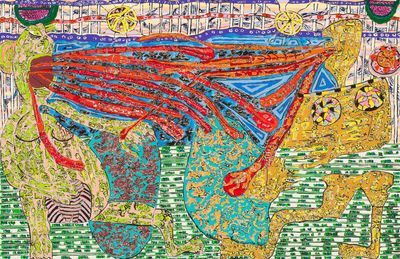

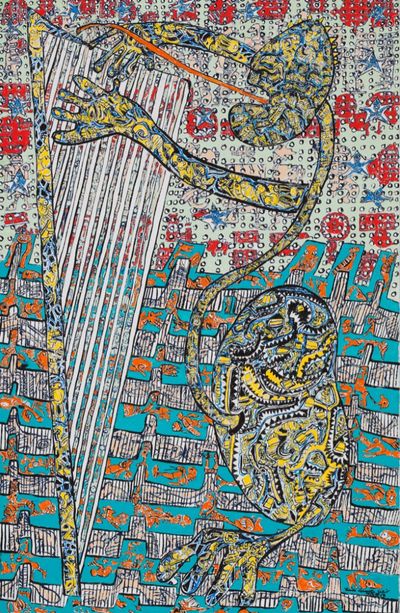

The concept of Form is not merely about external shape; it delves into the internal organization, structure, and coherence that gives an artwork its integrity and distinct identity. It is the framework that allows for meaning to emerge and for Quality to be judged.

- Internal Coherence: A well-formed artwork exhibits internal consistency, where all its parts contribute to the whole. Whether it's the narrative structure of a tragedy, the compositional balance of a painting, or the rhythmic patterns of music, Form dictates this coherence.

- Expression and Meaning: The artist uses Form to express ideas, emotions, or narratives. A sculptor shapes clay to convey movement or despair; a poet arranges words into meter and rhyme to evoke a specific feeling. The mastery of this shaping process directly impacts the artwork's communicative power.

- Quality as Realized Form: The Quality of an artwork is often assessed by how effectively its form serves its purpose or theme. Is the composition balanced? Is the narrative compelling? Is the execution skillful? A high-Quality artwork is one where the chosen Form is impeccably realized, allowing its inherent Beauty or truth to shine through. This realization requires not just technical skill but also profound insight into the material and the message.

(Image: A detailed drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, emphasizing the geometric and proportional harmony of the human body inscribed within a circle and a square, symbolizing the ideal form and beauty derived from mathematical principles.)

IV. The Interplay: Art, Form, Beauty, and Quality

The relationship between Art, Form, Beauty, and Quality is cyclical and interdependent.

- Art as the Act of Forming: The creation of Art is fundamentally an act of giving Form to something – an idea, an emotion, a material. The artist selects, arranges, and structures elements to create a distinct entity.

- Form as the Vehicle for Beauty: It is through the form that Beauty is made manifest. Whether it's the elegant symmetry of a classical sculpture or the unsettling asymmetry of a modern piece, the arrangement of elements evokes an aesthetic response. The form itself can be beautiful, or it can serve to illuminate a deeper Beauty.

- Quality as the Success of Form: The Quality of the artwork is determined by the success of its form – how well it achieves its intended effect, how skillfully it is executed, and how profoundly it resonates with the viewer or listener. A poorly executed form, no matter how noble the intention, diminishes Quality.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, in his Aesthetics, viewed Art as the sensuous manifestation of the Absolute Idea. For Hegel, Art is one of the ways the Spirit comes to know itself, and this self-knowledge is embodied in concrete forms. The Beauty of art arises when the spiritual content is perfectly fused with its sensuous form, achieving a harmonious unity that transcends mere imitation. The Quality of art, then, lies in the clarity and depth with which this spiritual content is made manifest through its form.

V. Concluding Reflections: An Ongoing Dialogue

The nature of Art and Form remains a vibrant and contested field, continuously re-examined as new artistic movements emerge. Yet, the foundational questions posed by the philosophers of the Great Books of the Western World endure: What constitutes Form? How does it relate to Beauty? And what makes one artwork possess greater Quality than another?

Ultimately, to engage with Art is to engage with form – to perceive its structure, appreciate its design, and understand how it shapes our experience of Beauty and Quality. It is through this engagement that Art continues to challenge, inspire, and illuminate the human condition.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms Explained""

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kant's Aesthetics: The Critique of Judgment Summary""