The Enduring Nexus: Exploring the Nature of Art and Form

Art, in its myriad manifestations, has long served as a profound mirror to the human soul, reflecting our aspirations, fears, and the very structure of our perception. At its core, any meaningful discussion of art inevitably leads us to the concept of Form. This article delves into the intricate relationship between art and form, exploring how philosophical traditions, particularly those illuminated by the Great Books of the Western World, have sought to define, understand, and appreciate the intrinsic Beauty and Quality that emerges when these two elements coalesce. We shall see that form is not merely a container for content, but an active participant in shaping meaning, eliciting emotion, and ultimately, defining the essence of art itself.

The Inseparable Dance: Art and the Essence of Form

From the earliest cave paintings to the most avant-garde digital installations, art has always been an endeavor to give shape, structure, and definition to experience. This act of definition is precisely where Form becomes indispensable. Form, in a philosophical sense, refers to the underlying structure, organization, and essential character of a thing—that which makes it what it is. In art, form is the arrangement of elements, the composition, the rhythm, the balance, the very blueprint that guides the artist's hand and the viewer's eye.

Without form, art risks dissolving into chaos, an undifferentiated mass of expression lacking coherence or communicative power. Conversely, form without content can be sterile, a mere exercise in technical skill devoid of soul. The true magic lies in their inseparable dance, where form elevates content, and content imbues form with significance.

Echoes of Antiquity: Plato, Aristotle, and the Pursuit of Beauty

The philosophical foundations for understanding art and form are deeply rooted in classical thought, particularly in the works of Plato and Aristotle, central figures in the Great Books.

-

Plato's Ideal Forms and the Mimetic Art: For Plato, as articulated in dialogues like The Republic, true Form resides in a transcendent realm of perfect, unchanging Ideals. Earthly objects, including works of art, are mere shadows or imitations (mimesis) of these perfect Forms. A beautiful statue, for instance, is beautiful because it partakes, however imperfectly, in the Form of Beauty itself. This perspective suggests that the Quality of art is measured by its ability to reflect, or at least point towards, these higher, more perfect Forms. The artist, in striving for Beauty, is in a sense trying to capture a glimpse of this ultimate reality.

-

Aristotle's Immanent Forms and the Purpose of Art: Aristotle, while acknowledging the importance of form, brought it down from the Platonic heavens. For Aristotle, as explored in his Poetics, the form of a thing is inherent within the thing itself, not separate from it. The form of a tragedy, for example, lies in its specific structure: its plot, character, thought, diction, song, and spectacle, all working together to achieve its purpose (catharsis). Here, Form is intrinsically linked to function and purpose. The Quality of a work of Art is judged by how well its constituent parts are organized to achieve its intended effect and how truly it represents universal truths, not just particular instances.

| Philosopher | View on Form in Art | Emphasis on Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Plato | Transcendent, ideal; art imitates perfect Forms. | Fidelity to ideal Beauty; spiritual resonance. |

| Aristotle | Immanent, inherent; form defines structure and purpose. | Coherence, effective execution of purpose; universal truth in particular. |

The Indispensable Role of Quality: Beyond Mere Appearance

The discussion of art and form is incomplete without a profound appreciation for Quality. What distinguishes a masterpiece from a mere craft? It is not simply the presence of form, but the Quality of that form—how thoughtfully it is conceived, how masterfully it is executed, and how profoundly it resonates.

- Form as a Vehicle for Quality: In great art, form is not a superficial veneer but the very medium through which Quality is expressed. Consider a symphony: its form (sonata form, fugue, etc.) is the skeleton, but the Quality comes from the composer's genius in weaving melody, harmony, and rhythm within that structure, creating moments of breathtaking Beauty and emotional depth.

- The Subjectivity and Objectivity of Quality: While Beauty can be subjective, the Quality of form often possesses an objective dimension. A well-constructed narrative, a balanced composition, or a harmonious color palette often adhere to principles that transcend individual taste, principles often explored by philosophers like Kant, who sought universal principles of aesthetic judgment, even while acknowledging subjective experience. The Great Books consistently return to the idea that some works possess an enduring Quality that speaks across generations and cultures, suggesting a deeper, more universal appeal rooted in their intrinsic formal excellence.

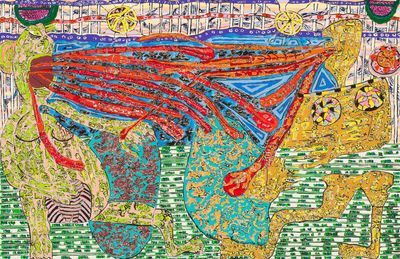

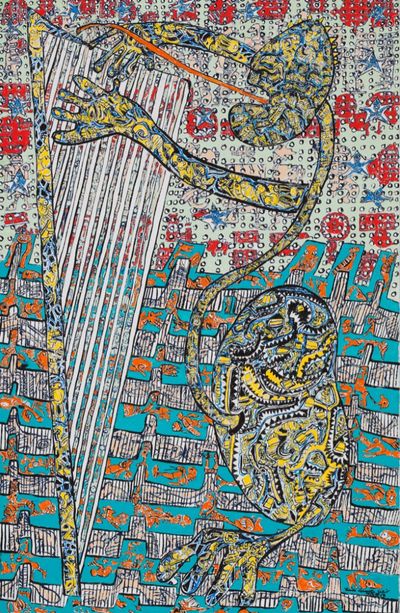

Evolution of Form: From Representation to Abstraction

The understanding and application of form in art have evolved dramatically throughout history. While classical art often emphasized representational forms that mimicked the observable world, later movements challenged these conventions:

- Renaissance and Classical Forms: Revival of classical ideals, emphasizing harmony, proportion, and perspective to create realistic and idealized forms.

- Baroque and Dynamic Forms: Emphasis on movement, drama, and emotional intensity, often employing complex, swirling forms and chiaroscuro.

- Romanticism and Expressive Forms: Prioritizing individual emotion and subjective experience, often leading to more fluid, less rigid forms.

- Modernism and Abstract Forms: A radical departure, where Form itself becomes the subject. Artists like Kandinsky or Mondrian explored the expressive power of pure lines, shapes, and colors, divorcing form from direct representation, yet still seeking Beauty and Quality in their abstract compositions. Here, the internal logic and structure of the artwork's form become paramount.

This evolution underscores a continuous philosophical inquiry into what constitutes Form and how it serves the ever-expanding definition of Art.

(Image: A detailed drawing of Plato and Aristotle standing together in a classical setting, perhaps within Raphael's "The School of Athens." Plato points upwards, symbolizing his theory of Forms, while Aristotle gestures horizontally, indicating his focus on the immanent world. Both figures are depicted with thoughtful expressions, engaged in deep philosophical discourse, surrounded by architectural elements that evoke ancient Greek wisdom.)

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Meaning Through Form

The nature of art and form is a philosophical labyrinth that continues to fascinate and challenge us. From the ancient Greek pursuit of ideal Beauty to the modernist exploration of abstract Quality, the dialogue between art and form remains central to our understanding of human creativity and perception. The Great Books of the Western World provide an indispensable foundation for this inquiry, offering timeless insights into how artists, through the mastery of Form, strive not merely to create objects, but to manifest meaning, evoke emotion, and ultimately, reveal deeper truths about existence itself. In every line, every brushstroke, every note, and every word, the artist grapples with form, seeking to imbue it with a Quality that transcends the ephemeral and touches upon the eternal.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms Explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Poetics Summary - What makes a good tragedy?""