The Enduring Inquiry: Unpacking the Nature of Art and Form

The essence of art, its underlying form, and our perception of its beauty and quality have captivated philosophers for millennia. From the ancient Greeks to contemporary thinkers, the debate persists: Is art merely imitation, a window to higher truths, or a subjective expression? This article delves into these fundamental questions, drawing on the rich tapestry of thought found within the Great Books of the Western World, to explore how form gives art its structure, enabling it to evoke beauty and possess discernible quality.

What is Art? A Philosophical Lens

The very definition of art is a contested terrain. For many classical thinkers, particularly Aristotle, art was understood as mimesis, or imitation. In his Poetics, Aristotle posits that art imitates nature, not merely in a superficial sense, but by representing universal truths and possibilities. A tragedy, for instance, imitates actions that evoke pity and fear, thereby achieving a catharsis.

Plato, in contrast, viewed art with suspicion. For him, as explored in The Republic, the material world itself is an imperfect copy of the true, eternal Forms. Art, being an imitation of this already imperfect world, is therefore twice removed from ultimate reality. It can mislead, appealing to emotion rather than reason, and potentially corrupting the soul. Yet, even Plato acknowledged a certain beauty in harmony and order, reflecting a divine structure.

The tension between art as imitation and art as a vehicle for truth, emotion, or pure aesthetic experience forms the bedrock of our inquiry into its nature.

The Primacy of Form: Structure and Essence

At the heart of any discussion about art lies the concept of form. Form refers to the structure, organization, and essence that gives a work of art its particular identity. It’s not just the external shape but the internal arrangement of parts that makes the whole coherent and meaningful.

Plato's Ideal Forms:

For Plato, the concept of Form was central to his metaphysics. The Form of Beauty, for example, exists independently in an ideal realm, immutable and perfect. Any beautiful object in our world is beautiful only insofar as it participates in, or imperfectly reflects, this ideal Form. Thus, a sculptor striving for beauty is, consciously or unconsciously, aiming to capture a glimpse of this transcendent ideal.

Aristotle's Formal Cause:

Aristotle offered a more immanent understanding. In his theory of the four causes, the formal cause is the blueprint or essence of a thing – what it is. For a statue, its form is the idea or design in the sculptor's mind; for a play, it’s the plot, the arrangement of incidents that gives the story its shape and meaning. The form is what makes a thing intelligible and determines its quality. Without a coherent form, a collection of elements remains just that – a collection, not a unified work of art.

Consider the following distinction:

| Aspect of Art | Platonic View of Form | Aristotelian View of Form |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Transcendent, ideal realm | Immanent, inherent in the object |

| Relation to Art | Art imperfectly imitates | Art embodies and reveals |

| Purpose | Guiding principle for beauty | Structural essence, defining identity |

| Impact on Quality | Art's quality tied to closeness to ideal | Art's quality tied to skillful embodiment of its structure |

Beauty: The Aesthetic Experience and its Foundations

The pursuit of beauty is often seen as one of art's highest aims. But what exactly is beauty? Is it an objective property residing in the artwork, or a subjective experience of the beholder?

Classical aesthetics, heavily influenced by Pythagorean thought and Plato's Timaeus, often linked beauty to proportion, harmony, and order. A beautiful object possessed balanced ratios and an inherent symmetry that was believed to reflect cosmic order. This perspective suggests beauty is an objective attribute, discernible through reason and mathematical principles. For something to possess quality, it must first exhibit this harmonious form.

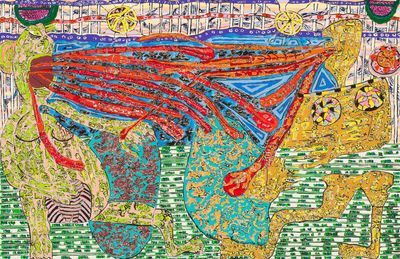

(Image: A detailed depiction of Plato and Aristotle engaged in discussion, standing before a classical Greek temple facade, with a geometric diagram representing ideal proportions subtly overlaid in the background.)

However, later philosophers, notably Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgment, explored the subjective dimension of beauty. While acknowledging a universal agreement on certain aesthetic judgments, Kant argued that the experience of beauty arises from the free play of our cognitive faculties, a feeling of pleasure that is disinterested and universalizable, yet ultimately subjective in its origin.

The interplay between objective form and subjective experience creates the complex tapestry of aesthetic judgment. A work of art with impeccable form might be universally acknowledged for its beauty, yet individual responses can vary widely.

Quality: The Measure of Artistic Excellence

How do we assess the quality of art? This question is intrinsically linked to form and beauty. A work of art's quality is often judged by its mastery of form, its capacity to evoke beauty, and its effectiveness in achieving its artistic purpose.

For Aristotle, the quality of a tragedy was measured by its plot (its form), its character development, thought, diction, song, and spectacle, all contributing to the desired effect of catharsis. A well-constructed plot, with a clear beginning, middle, and end, and logical causality, indicates high quality.

Factors contributing to artistic quality include:

- Mastery of Technique: The artist's skill in handling their medium and executing their vision.

- Coherence of Form: The internal consistency and structural integrity of the artwork.

- Originality and Innovation: The artist's ability to present new perspectives or push the boundaries of their craft.

- Emotional and Intellectual Impact: The artwork's capacity to move, challenge, or enlighten the audience.

- Truthfulness (Mimesis): How effectively the art reveals universal truths or aspects of human experience.

- Enduring Relevance: The work's ability to speak to different generations and cultures.

Ultimately, the quality of a work of art is a complex judgment, blending objective criteria related to its form and execution with subjective appreciation of its beauty and impact. Philosophers continue to grapple with whether universal standards of quality truly exist, or if all judgments are ultimately culturally and individually relative.

The Interwoven Fabric of Art, Form, Beauty, and Quality

In conclusion, the nature of art is an intricate philosophical puzzle, where form serves as the fundamental scaffolding. It is through coherent and masterful form that a piece of art can aspire to beauty and achieve lasting quality. Whether art is seen as an imitation of nature, an expression of the divine, or a subjective experience, these four concepts remain inextricably linked, offering a framework for understanding and appreciating the profound impact of creative endeavor on the human spirit. The ongoing dialogue, initiated by the giants of Western thought, continues to enrich our understanding of what it means to create, perceive, and value art.

Further Exploration

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato's Theory of Forms Explained"

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Poetics Summary and Analysis"