A Philosophical Inquiry into the Nature of Art and Form

The essence of Art often feels elusive, a whisper of the divine or a profound human expression. Yet, upon closer examination, we find that this essence is inextricably bound to Form. This article delves into the symbiotic relationship between Art and Form, exploring how the structured organization of elements gives rise to aesthetic experience, how Beauty emerges from this intricate dance, and the inherent Quality that elevates mere material into something transcendent. From the ancient Greeks to modern aesthetics, philosophers have grappled with how Form is not merely a container for Art, but rather its very constitution, shaping our perception and understanding of what is truly beautiful and well-crafted.

The Inseparable Dance of Art and Form

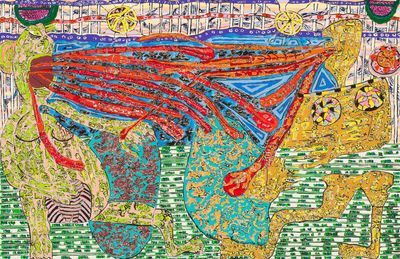

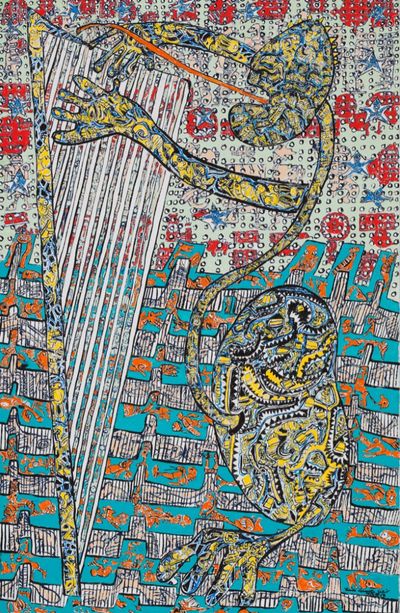

To speak of Art without acknowledging Form is akin to discussing thought without language. Form is the structure, the arrangement, the blueprint that gives Art its tangible existence. Whether it's the rhythmic cadence of a poem, the harmonious proportions of a sculpture, or the compositional balance of a painting, Form provides the framework through which artistic intent is conveyed. Aristotle, pondering the nature of being, posited that every physical object is a composite of matter and Form. In the realm of Art, this takes on a profound significance: the artist imposes Form upon raw matter—be it paint, stone, sound, or words—to create something new, something that embodies an idea or evokes an emotion.

Consider the meticulous Form of a sonnet, with its strict rhyme scheme and meter, or the architectural Form of a Gothic cathedral, where every arch and buttress contributes to a unified, soaring Quality. These are not arbitrary choices but deliberate applications of Form to achieve a particular effect, to express a specific vision. The Quality of the Form directly impacts the Quality of the Art.

Form as the Blueprint of Being

Beyond its role in Art, Form holds a fundamental place in philosophical inquiry into reality itself. For Plato, Form (or Idea) was the eternal, perfect archetype existing independently of the physical world, of which all earthly manifestations are but imperfect copies. While an artist might not literally copy a Platonic Form, the aspiration for perfection, for an ideal Quality in their work, echoes this ancient concept. The pursuit of Beauty in Art is often a striving towards an ideal Form.

Form is not just about physical shape; it encompasses organization, pattern, and structure. It is the Quality that defines a thing, distinguishing it from mere undifferentiated matter. A tree has the Form of a tree, a human being the Form of a human being. In Art, this means that a piece is not just a collection of colors or sounds, but a structured whole, where each element contributes to the overall Form and thereby to its intrinsic Quality and meaning.

The Pursuit of Beauty Through Form

The connection between Form and Beauty is perhaps the most compelling aspect of this philosophical exploration. Why do certain arrangements of lines, colors, sounds, or words strike us as beautiful? Philosophers throughout history have offered various answers, but many converge on the idea that Beauty is often perceived when Form exhibits certain characteristics.

Medieval thinkers like Thomas Aquinas identified three conditions for Beauty: integritas (integrity or perfection), consonantia (proportion or harmony), and claritas (radiance or clarity). All three are attributes of Form. A work of Art possesses Beauty when its Form is complete and whole, when its parts are harmoniously arranged, and when its essence shines through with clarity. The Quality of these formal elements directly contributes to our experience of Beauty.

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Judgment, explored aesthetic judgment, suggesting that Beauty is found in the "purposiveness without purpose" of an object's Form. We perceive a Form as beautiful when it appears designed or perfectly suited for an unknown purpose, evoking a feeling of pleasure without serving any practical end. This highlights the intrinsic Quality of the Form itself, independent of its utility.

Let's consider how different philosophical traditions have viewed this intricate relationship:

- Platonic Idealism: Art is an imitation (mimesis) of the ideal, eternal Forms. The Beauty of Art lies in its ability to reflect these perfect archetypes.

- Aristotelian Realism: Form is inherent in matter; Art reveals or perfects the Form within the material, bringing potential into actuality. Beauty arises from the skillful actualization of Form.

- Medieval Scholasticism: Beauty is a transcendental property of being, characterized by the Quality of Form through integrity, proportion, and clarity.

- Kantian Aesthetics: Beauty is a subjective but universal judgment arising from the contemplation of a Form's "purposiveness without purpose," where the Quality of the Form stimulates our faculties.

(Image: A detailed classical drawing, perhaps a Vitruvian Man or a Renaissance architectural sketch, illustrating principles of proportion, symmetry, and geometric harmony. The lines are precise, demonstrating the artist's understanding of ideal Form and its relation to Beauty.)

The Artist's Quality and the Viewer's Experience

The role of the artist is paramount in imbuing Quality into the Form. Their skill, vision, and dedication determine the level of perfection achieved in the Art. It is the artist who makes choices about composition, color, texture, rhythm, and narrative structure—all elements of Form—to communicate their unique perspective and to evoke a particular response. The Quality of the Form is not accidental; it is the result of deliberate craft and profound insight.

When we, as viewers, engage with Art, our experience is profoundly shaped by its Form. A poorly executed Form can obscure the most profound message, while a masterful Form can elevate even a simple subject. The emotional resonance, the intellectual stimulation, the sheer delight we derive from Art are all, in essence, responses to the Quality of its Form. It is through the structured presentation of elements that Art transcends the mundane and touches upon the sublime.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Form in Art

The relationship between Art and Form is not merely academic; it is the very pulse of creative endeavor. Form provides the discipline, the structure, and the framework necessary for Art to manifest and to achieve its highest Quality. It is the vehicle through which Beauty is made perceptible, transforming raw material into meaningful expression. Understanding Form is not just understanding how Art is made, but how it communicates, how it moves us, and how it reflects our deepest philosophical inquiries into Beauty, order, and the nature of existence itself. The enduring legacy of Form in Art is a testament to its fundamental Quality as both a philosophical concept and an aesthetic imperative.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms explained" and "Aristotle on Art and Mimesis""