Probing the Depths: The Nature of Animal Consciousness

The question of animal consciousness is not merely a scientific inquiry; it is a profound philosophical journey that challenges our anthropocentric views and compels us to reconsider our place within the vast tapestry of life. This pillar page delves into the multifaceted nature of animal consciousness, exploring historical perspectives, contemporary evidence, and the profound ethical implications of recognizing minds beyond our own. Far from being a niche topic, understanding the mind of other species is central to how we define consciousness itself and our moral responsibilities within the natural world.

Defining the Indefinable: What is Consciousness?

Before we can ask if animals are conscious, we must grapple with the elusive concept of consciousness itself. Philosophers have debated its definition for millennia, often struggling to pin down a phenomenon that is inherently subjective.

At its core, consciousness refers to the state of being aware of one's own existence and surroundings. However, this umbrella term encompasses several distinct facets:

- Sentience: The capacity to feel, perceive, or experience subjectively. This includes the ability to feel pain, pleasure, fear, or comfort.

- Awareness: The state of knowing or perceiving something. This can range from basic sensory awareness to complex cognitive understanding.

- Self-Awareness: The capacity for introspection and the recognition of oneself as a distinct individual entity, separate from others and the environment.

- Phenomenal Consciousness (Qualia): The subjective, qualitative aspects of experience – what it feels like to see red, hear a melody, or taste chocolate. This is often referred to as the "hard problem" of consciousness.

Historically, the Great Books have offered various frameworks. Aristotle, in works like De Anima, distinguished between different types of souls: the vegetative (for growth and reproduction), the sensitive (for sensation and movement, present in animals), and the rational (unique to humans, for thought and reason). This early classification acknowledged animal sensation but placed human reason on a distinct, higher plane.

A Historical Voyage Through Animal Minds

The philosophical understanding of animal mind has undergone dramatic shifts, reflecting prevailing scientific and cultural paradigms.

Ancient Insights and Hierarchies

Ancient Greek philosophers often placed humans at the apex of a natural order, yet acknowledged animals' capabilities. As mentioned, Aristotle's scala naturae (ladder of nature) positioned animals with "sensitive souls," capable of perception, desire, and movement, but lacking the rational soul of humans. This view, found in De Anima, granted animals a form of consciousness tied to their senses and immediate needs, distinguishing them sharply from plants but also from human intellect.

The Cartesian Divide: Animals as Automata

Perhaps the most influential and controversial view emerged with René Descartes in the 17th century. In his Discourse on Method and Meditations, Descartes argued for a radical dualism: the mind (res cogitans) was a non-physical, thinking substance, while the body (res extensa) was purely mechanistic. Crucially, he asserted that animals, lacking a rational soul, were mere machines, complex automata devoid of genuine consciousness, feeling, or thought. Their cries of pain, he contended, were no different from a clock chiming. This perspective, deeply embedded in Western thought, profoundly influenced scientific and ethical approaches to animals for centuries.

Enlightenment and Beyond: Glimmers of Continuity

The Enlightenment began to challenge the strict Cartesian divide. Thinkers like John Locke, in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, explored how ideas originate from sensation and reflection, a process that could potentially apply, in varying degrees, to animals. David Hume, in An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, observed that animals learn from experience and make inferences, suggesting a continuity of mental faculties, albeit simpler ones, between humans and other species.

The most significant shift, however, came with Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. By establishing the evolutionary continuity of all life, Darwin provided a biological framework for the continuity of mental faculties. If humans evolved from other species, it became plausible, even likely, that our cognitive and emotional capacities have evolutionary precursors in the animal mind.

Key Historical Perspectives on Animal Consciousness

| Era | Key Philosophers/Ideas | View on Animal Consciousness | Source (GBWW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient | Aristotle (Scala Naturae, Sensitive Soul) | Animals possess sensitive souls, capable of sensation, perception, and desire, but lack rational thought. They experience the world through their senses. | De Anima (Aristotle) |

| 17th Century | René Descartes (Mechanistic View, Res Extensa) | Animals are complex machines, mere automata without souls, mind, or consciousness. Their behaviors, including reactions to pain, are purely mechanical reflexes. | Discourse on Method, Meditations on First Philosophy (Descartes) |

| 18th-19th Century | David Hume (Continuity of Experience), Charles Darwin (Evolutionary Continuity) | Animals learn from experience and make inferences, suggesting shared, albeit simpler, cognitive processes. Evolutionary theory posits a continuity of mental faculties across species, challenging human exceptionalism in consciousness. | An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (Hume), On the Origin of Species, The Descent of Man (Darwin - while not strictly GBWW, his influence is foundational) |

Peeking Behind the Veil: Evidence for Animal Consciousness

Modern science, combined with rigorous philosophical inquiry, offers compelling evidence that many animals possess forms of consciousness. This evidence comes from various fields:

Behavioral Observations

Detailed ethological studies reveal complex behaviors that are difficult to explain without invoking some level of conscious awareness:

- Tool Use and Problem-Solving: Chimpanzees using sticks to fish for termites, crows bending wire to retrieve food, otters using rocks to crack shells. These suggest foresight, planning, and understanding of cause and effect.

- Complex Social Structures: Elephants exhibiting grief, primates demonstrating empathy, wolves engaging in intricate cooperative hunting. These behaviors point to emotional depth and social cognition.

- Self-Recognition: The "mirror test" (recognizing oneself in a reflection) has been passed by great apes, dolphins, elephants, and some birds, suggesting a form of self-awareness.

- Deception and Strategic Behavior: Animals like vervet monkeys using alarm calls to scare off rivals from food, or birds feigning injury to protect their young, indicate an understanding of others' beliefs and intentions.

Neurological Correlates

Advances in neuroscience provide physiological evidence for animal consciousness:

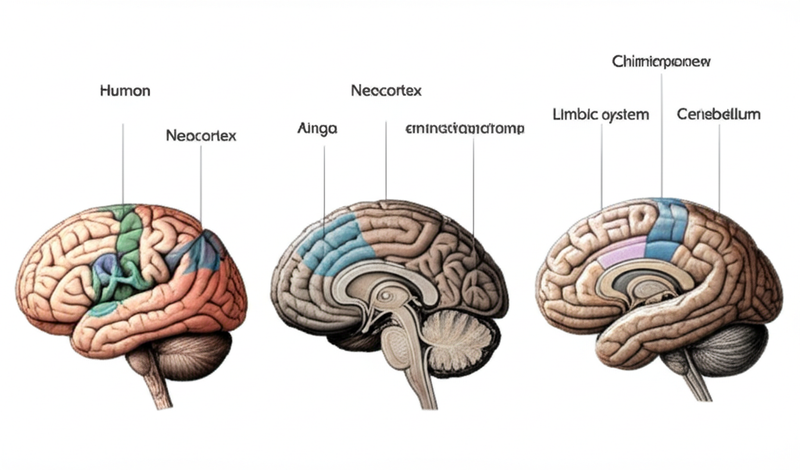

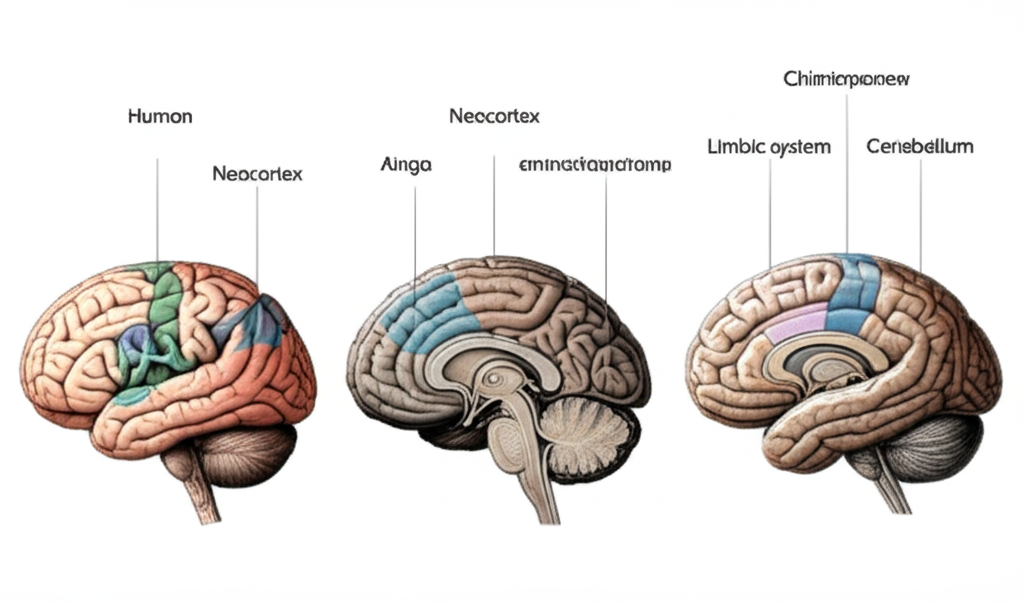

- Similar Brain Structures: Many animals, particularly mammals and birds, possess brain structures (e.g., limbic system, neocortex equivalents) analogous to those involved in human emotions, memory, and cognitive processing.

- Neurochemical Similarities: The presence of similar neurotransmitters (like dopamine, serotonin) and hormones associated with pain, pleasure, fear, and attachment in humans suggests similar subjective experiences in animals.

- Neural Activity Patterns: Studies using fMRI and EEG show patterns of brain activity in animals that resemble those observed in conscious humans when experiencing emotions or engaging in cognitive tasks.

- The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness (2012): A landmark statement by a group of prominent neuroscientists, stating that "non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess the neurological substrates of consciousness."

The Weight of Awareness: Ethical Implications

If animals possess consciousness, the ethical implications are profound and far-reaching. The recognition of animal mind challenges us to re-evaluate our moral responsibilities towards other species.

- Animal Welfare: If animals can experience pain, suffering, pleasure, and fear, then we have a moral obligation to minimize their suffering and promote their well-being. This underpins movements for humane treatment in agriculture, research, and entertainment.

- Animal Rights: Some philosophers argue that if animals possess certain cognitive and emotional capacities, they may be entitled to fundamental rights, such as the right to life, freedom from cruelty, and the right to live according to their nature. This view often draws inspiration from utilitarian thought (e.g., Jeremy Bentham's famous dictum: "The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?") or deontological arguments adapted from figures like Immanuel Kant, though Kant himself focused primarily on rational beings.

- Dietary Choices: The acknowledgment of animal sentience is a central pillar of vegetarian and vegan philosophies, arguing that consuming animal products is unethical if viable alternatives exist and cause less suffering.

- Conservation: Understanding the complex inner lives of animals can deepen our appreciation for biodiversity and strengthen arguments for protecting species and their habitats, recognizing their inherent value beyond their utility to humans.

The philosophical debate here often revolves around the criteria for moral consideration. Is it sentience alone? Or does it require higher cognitive functions like self-awareness or rationality? The more we learn about animal consciousness, the more complex and urgent these ethical questions become.

Uncharted Territories: Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, understanding the nature of animal consciousness remains a formidable challenge.

- The Problem of Subjectivity: We can observe behavior and brain activity, but we can never truly experience the world from an animal's perspective. The "what it's like" question (qualia) remains difficult to access directly.

- Avoiding Anthropomorphism: A key challenge is to interpret animal behavior without projecting human emotions and cognitive processes onto them inappropriately. While continuity is plausible, differences must also be acknowledged.

- The Spectrum of Consciousness: Is consciousness an all-or-nothing phenomenon, or does it exist on a spectrum, with varying degrees of complexity across different species? Where do insects, fish, or even plants fit into this discussion?

- Methodological Limitations: Studying non-verbal, non-human minds requires innovative and interdisciplinary approaches, combining ethology, neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy.

Future directions in this field will likely involve refining our definitions of consciousness, developing more sophisticated observational and neuroscientific tools, and continuing to engage in rigorous philosophical debate to interpret the growing body of empirical evidence. The journey to truly understand the animal mind is far from over, promising profound insights not only into other species but into the very essence of our own nature.

Exploring Further: The Animal Mind

The journey into the nature of animal consciousness is one of the most exciting and ethically charged frontiers in philosophy and science. It demands humility, open-mindedness, and a willingness to question long-held assumptions about our unique place in the world. As we continue to uncover the rich inner lives of other species, we are compelled to redefine what it means to be a conscious being and, in doing so, to re-evaluate our responsibilities to the incredible diversity of life that shares our planet.

YouTube Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness Explained""

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""What is it like to be a bat Thomas Nagel explained""