The Enduring Puzzle of Universal Ideas: Do They Truly Exist?

The metaphysical status of universal ideas is one of philosophy's most profound and persistent questions. At its heart, it asks: Do abstract concepts like "redness," "justice," or "humanness" exist independently of our minds and the particular instances we observe, or are they merely mental constructs or names we apply? This isn't just an academic exercise; our answer profoundly shapes our understanding of reality, knowledge, and even language itself. From the towering intellects of ancient Greece to the intricate debates of the Middle Ages, the nature of universals – those qualities or relations that can be predicated of many particulars – has been a cornerstone of metaphysics, challenging us to define the very fabric of existence beyond the tangible.

Unpacking the Distinction: Universal and Particular

Before we delve into the various answers, it's crucial to grasp the fundamental distinction between the universal and the particular.

- A particular is a specific, individual instance of something. Think of this red apple, that specific human being named Sarah, or that unique triangular sign. Particulars exist in space and time, are tangible, and are unique.

- A universal, conversely, is a quality, property, or relation that can be shared by many particulars. "Redness" is a universal that applies to many red apples, red cars, and red sunsets. "Humanness" is a universal shared by Sarah, John, and every other individual human. "Triangularity" is a universal property of all triangles.

The core metaphysical question then becomes: What is the nature of "redness" itself? Does it have an existence apart from all red things? If so, where and how does it exist?

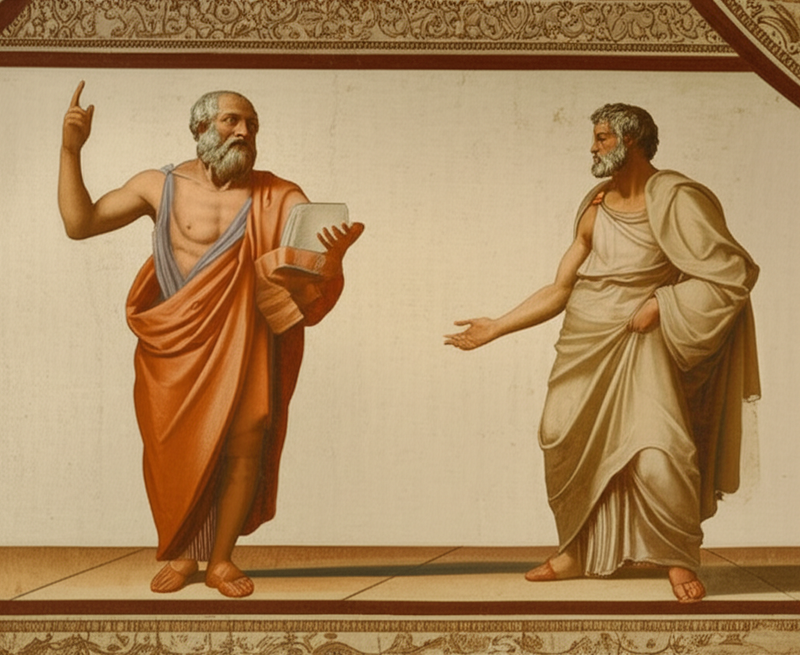

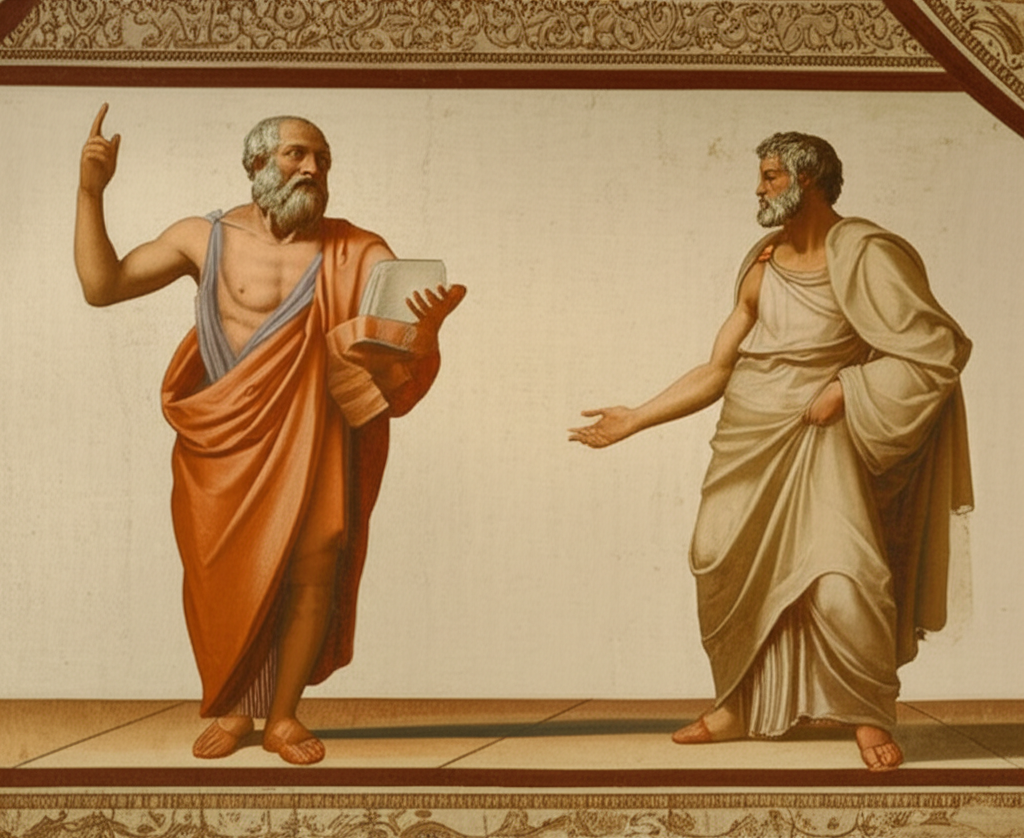

Plato's Realm of Forms: Ideas as Independent Realities

One of the most influential and enduring answers to the problem of universals comes from Plato, as explored extensively in the Great Books of the Western World, particularly in works like the Republic, Phaedo, and Parmenides. Plato proposed that universals, which he called Forms or Ideas, possess an independent, eternal, and non-physical existence.

For Plato:

- Existence Beyond Particulars: The Form of "Beauty" exists independently of any beautiful person, painting, or sunset. These particulars merely participate in or imitate the perfect, unchanging Form.

- Perfection and Immutability: The Forms are perfect, eternal, and unchanging. While particular beautiful things fade or decay, the Form of Beauty itself remains pristine.

- The True Reality: Plato argued that the Forms constitute the ultimate reality, a realm accessible only through intellect and reason, not through the senses. The physical world we perceive is merely a shadow or imperfect copy of this higher reality.

This view, often termed Platonic Realism, asserts that universals have a robust metaphysical status as truly existent entities, more real, in a sense, than the fleeting particulars we encounter daily. They provide the very blueprint for everything that exists in our sensory world.

Aristotle's Immanent Universals: Forms Within Particulars

Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, presented a powerful alternative, also extensively detailed in the Great Books, notably in his Categories and Metaphysics. While he agreed that universals are real and essential for knowledge, Aristotle fundamentally disagreed with Plato's notion of a separate realm of Forms.

For Aristotle:

- Forms in Particulars: Universals (or "Forms," though used differently than Plato) do not exist independently of particular things. Instead, they exist within the particulars themselves as their essences. The "humanness" of Sarah exists in Sarah; it is not in a separate realm.

- Empirical Foundation: We come to understand universals by observing many particulars and abstracting the common features. Our knowledge of "redness" comes from seeing many red objects.

- No Separate Realm: There is no separate, transcendent world of Forms. Reality is primarily the world of individual substances (particulars), and universals are inherent properties or structures of these substances.

Aristotle's position, often called Aristotelian Realism or Immanent Realism, still grants universals a significant metaphysical status, but grounds their existence firmly within the concrete world. The universal is inseparable from the particular, existing in re (in the thing) rather than ante rem (before the thing).

The Medieval Debate: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The problem of universals continued to be a central concern in medieval philosophy, particularly within scholasticism. Philosophers grappled with reconciling Platonic and Aristotelian ideas with Christian theology. This era saw the development of three main positions:

| Position | Metaphysical Status of Universals | Key Idea | Proponents (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Realism | Universals exist independently (Platonic) or within particulars (Aristotelian). They are real entities. | Universals are substantial and precede or are inherent in particulars. | Plato, Aristotle, Anselm of Canterbury, Thomas Aquinas (modified) |

| Nominalism | Universals are merely names or labels we apply to groups of similar particulars. They have no objective existence. | Universals are post rem (after the thing) – products of language. | William of Ockham, Roscelin of Compiègne |

| Conceptualism | Universals are mental concepts or ideas formed by the mind, but they do not exist independently outside the mind. | Universals are in mente (in the mind) – mental constructs. | Peter Abelard, John Locke |

This table illustrates the spectrum of answers, ranging from the robust objective existence of universals in Realism to their complete subjective or linguistic nature in Nominalism. Conceptualism offers a middle ground, acknowledging mental concepts while denying external, independent existence.

Why Does This Metaphysical Debate Matter?

One might wonder why such an abstract debate about the metaphysical status of ideas holds any relevance. However, the implications are far-reaching:

- Epistemology (Theory of Knowledge): If universals are real, how do we know them? If they are just names, what does that say about the objectivity of our knowledge?

- Science: Do scientific laws describe truly existing universals (e.g., the universal properties of gravity), or are they convenient human constructs?

- Ethics: Is there a universal "Good" or "Justice" that transcends cultural differences, or are these merely culturally relative concepts?

- Language: How do words gain meaning if there's no shared universal concept they refer to? Does language create universals, or merely reflect them?

YouTube: "Plato's Theory of Forms Explained"

YouTube: "Aristotle on Universals and Particulars"

An Unresolved Yet Fundamental Question

The metaphysical status of universal ideas remains a vibrant and unresolved question in philosophy. Whether we lean towards the transcendent Forms of Plato, the immanent essences of Aristotle, the linguistic convenience of Nominalism, or the mental constructions of Conceptualism, our stance profoundly shapes our entire philosophical outlook. It forces us to confront the very nature of reality, the limits of human knowledge, and the intricate relationship between our minds, our language, and the world we inhabit. It is a testament to the enduring power of metaphysics that such an abstract inquiry continues to illuminate the deepest questions about existence itself.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas philosophy"