The Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas: Unpacking the Reality of Our Concepts

At the heart of metaphysics lies a profound question: What is the true nature and existence of universal ideas? Are concepts like 'redness,' 'justice,' or 'humanness' independent realities, mere names, or mental constructs? This article delves into the historical and philosophical journey to understand the metaphysical status of these universals, exploring how thinkers from Plato to the present have grappled with whether such ideas exist beyond the individual particulars we encounter. This enduring debate, often called the "Problem of Universals," challenges us to reconsider the very fabric of our reality and how we come to know it.

The Enduring Question: What is a Universal?

Hello, fellow travelers on the philosophical path! Have you ever paused to consider the very fabric of your thoughts? We speak of 'trees' and 'justice,' 'beauty' and 'numbers,' as if these ideas are readily understood. But what is a 'tree' beyond the specific oak outside your window, or the elm in the park? What is 'justice' apart from a particular legal ruling or a specific act of fairness? This, my friends, is the venerable 'Problem of Universals,' a cornerstone of metaphysics that has vexed and fascinated philosophers for millennia. It asks us to confront the deepest questions about reality, knowledge, and the very structure of our conceptual world.

The problem hinges on the distinction between the universal and the particular. A particular is an individual, concrete entity – this specific cat, that red apple, the act of kindness you witnessed yesterday. A universal, on the other hand, is a quality or relation that can be instantiated by many particulars – 'cat-ness,' 'redness,' 'kindness.' The core question then becomes: Do these universals exist, and if so, where and how? Are they real entities, or merely convenient linguistic tools?

Plato's Transcendent Forms: Ideas Beyond Our World

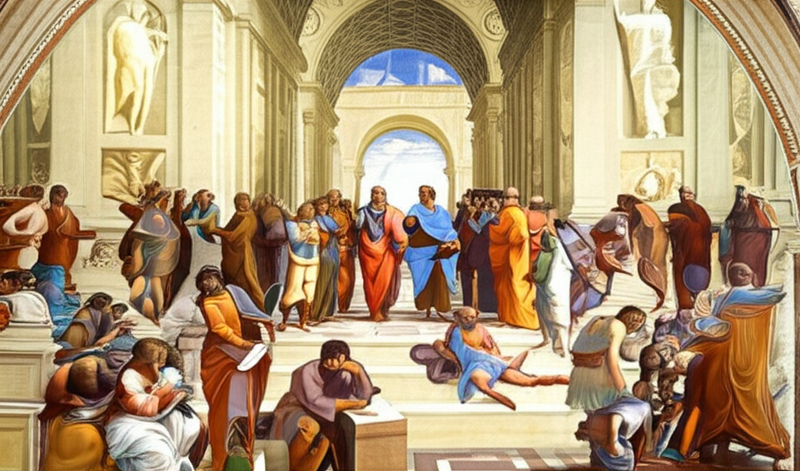

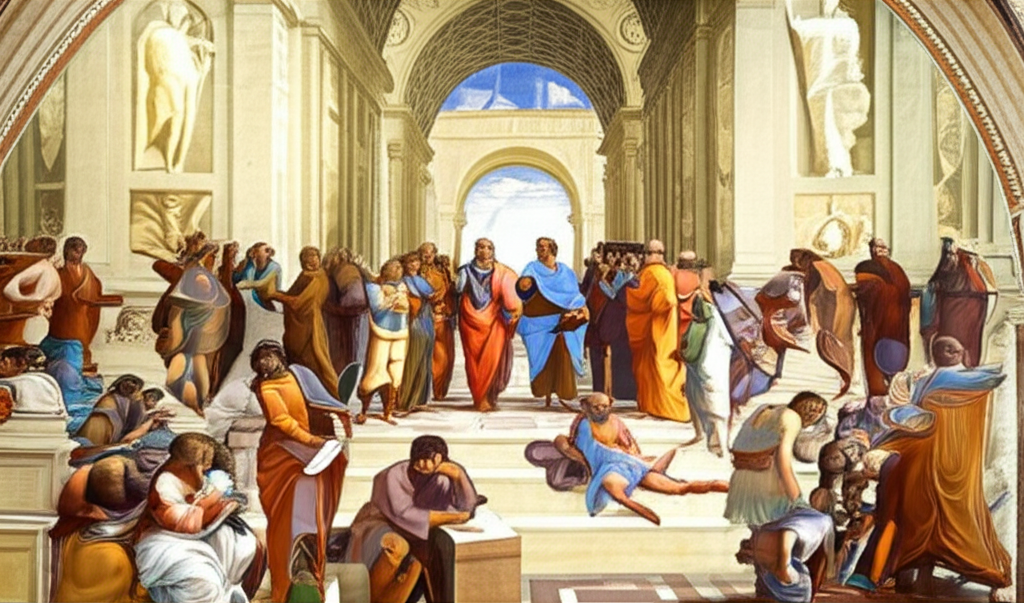

Our journey into the metaphysical status of universal ideas begins, as so many philosophical paths do, with Plato. For Plato, universals were not just mental abstractions; they were the most real things in existence. He posited a realm of perfect, eternal, and unchanging Forms (often translated as Ideas), existing independently of the physical world.

- The Realm of Forms: According to Plato, the 'Form of Beauty,' 'Form of Justice,' or 'Form of the Good' exists in a non-physical, intelligible realm. The beautiful objects or just actions we encounter in our sensory world are merely imperfect copies or reflections of these perfect Forms.

- Participation: Particulars in our world participate in these Forms. A red apple is red because it participates in the 'Form of Redness.' A just society is just because it strives to embody the 'Form of Justice.'

- Epistemological Significance: For Plato, true knowledge (episteme) could only be of these immutable Forms, not of the fleeting and changing particulars of the sensory world. Our minds, he believed, have some innate access or recollection of these Forms.

Plato's theory provides a robust answer to the metaphysical status of universals: they are real, objective, and exist in a superior, transcendent reality. This perspective is known as Platonic Realism.

Aristotle's Immanent Universals: Forms in the World

Stepping away from his teacher, Aristotle offered a different, yet still realist, account of universals. While he agreed that universals (which he also called Forms, though with a very different meaning than Plato's) were real, he firmly rejected the idea of a separate, transcendent realm.

- Forms within Particulars: For Aristotle, the Form of 'cat-ness' does not exist in a separate realm but is immanent within every individual cat. It is the essential nature or structure that makes a cat a cat.

- No Separation: You cannot have a 'Form of Cat' without a particular cat, nor can you have a particular cat without the 'Form of Cat.' They are inseparable.

- Abstraction: We come to know universals through abstraction. By observing many particulars (many cats), our minds can abstract the common Form or essence that they share.

Aristotle's view, often called Aristotelian Realism or Moderate Realism, grounds universals firmly within the sensible world, making them knowable through empirical observation and rational thought.

The Medieval Crossroads: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The debate over the metaphysical status of universal ideas intensified during the Middle Ages, becoming one of the most significant philosophical controversies. Scholars grappled with the implications of Plato's and Aristotle's views, leading to a spectrum of positions.

Here's a simplified overview of the main camps:

| Philosophical Position | View on Universal Ideas | Key Proponents |

|---|---|---|

| Realism | Universals are real entities, existing independently of our minds. | Platonic Realism: Universals (Forms) exist transcendentally (Plato, Anselm of Canterbury). |

| Moderate Realism: Universals exist within particulars and are abstracted by the mind (Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas). | ||

| Nominalism | Universals are merely names (nomina) or words we use to group similar particulars. They have no independent existence. | William of Ockham, Roscelin of Compiègne. |

| Conceptualism | Universals exist as mental concepts in the mind, formed by abstracting common features from particulars, but have no external reality. | Peter Abelard, John Locke (often seen as a conceptualist, though his views are nuanced). |

Nominalism, championed by thinkers like William of Ockham, radically challenged the realist positions. For nominalists, there is only the particular; 'cat-ness' is just the word 'cat' applied to many individual creatures. This position, often associated with Ockham's Razor (the principle that one should not multiply entities beyond necessity), argued against the existence of abstract entities.

Conceptualism offered a middle ground, suggesting that while universals are not independent, mind-external realities, they are more than just arbitrary names. They are valid mental constructs, formed by our intellects to organize and understand the world of particulars.

The Modern Mind: Ideas as Mental Constructs

The Enlightenment era brought new perspectives, particularly from British Empiricism. Philosophers like John Locke and David Hume shifted the focus from the external reality of universals to their psychological origin.

- Locke's Abstract Ideas: Locke believed that our minds form "abstract ideas" by observing many particulars and then stripping away their individual differences to retain only their common features. These abstract ideas are mental constructs, not independent entities.

- Berkeley's Critique: Bishop George Berkeley, a radical empiricist, challenged Locke, arguing that "abstract general ideas" are impossible. We can only imagine particular instances (e.g., a specific red apple), not a 'redness' that is neither light nor dark, large nor small. For Berkeley, what we call universals are simply particular ideas that are used to represent other similar particular ideas.

- Hume's Skepticism: David Hume pushed this further, suggesting that our tendency to group particulars under universal terms is a habit of mind, a psychological association rather than a reflection of an objective universal reality.

These modern perspectives leaned heavily towards a conceptualist or even nominalist understanding, emphasizing the role of the mind in creating or organizing our categories, rather than discovering pre-existing universal entities.

Why Does It Matter? The Enduring Legacy of Universals

The debate over the metaphysical status of universal ideas is far from a mere academic exercise. It underpins fundamental questions in various fields:

- Epistemology: How do we acquire knowledge? If universals are real, objective Forms, then knowledge might involve grasping these Forms. If they are just names, then knowledge is primarily about particulars and their relations.

- Ethics: Is there a universal 'Good' or 'Justice,' or are these concepts culturally relative and subjective? The answer profoundly impacts our understanding of moral truths.

- Science: Do scientific laws describe universal patterns inherent in nature, or are they human constructs for predicting particular events?

- Language: How does language refer to the world? If universals exist, then general terms refer to them. If not, how do general terms function meaningfully?

From the transcendent Forms of Plato to the mental constructs of the empiricists, the journey to understand universals is a testament to philosophy's enduring quest to map the contours of reality. While no single answer has satisfied all, the ongoing conversation continues to illuminate the profound connections between our thoughts, our language, and the world we inhabit. What, dear reader, do you believe is the true metaphysical status of these profound ideas?

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""The Problem of Universals Explained - Crash Course Philosophy""

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms: A Beginner's Guide""