Unveiling the Universal: What's Really Out There?

When we talk about "The Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas," we're diving into one of philosophy's most enduring and fascinating debates: Do general concepts like "redness," "justice," or "humanity" exist independently of the individual things that embody them, or are they merely mental constructs, or even just names we've assigned? This question, central to Metaphysics, explores the fundamental nature of reality, probing whether Universal qualities have an existence beyond the Particular instances we encounter every day. From Plato's transcendent Forms to the medieval nominalists' radical skepticism, philosophers have grappled with the profound implications of how we understand these abstract Ideas, shaping our views on knowledge, language, and the very fabric of existence.

The Enduring Puzzle: Universal and Particular

To unpack the Metaphysical status of Universal Ideas, we first need to clarify our terms. This isn't just semantics; it's about the fundamental categories through which we perceive and understand the world.

-

What Exactly is a Universal?

A Universal is a quality or characteristic that can be predicated of many Particular things. Think of "redness." We see a red apple, a red car, a red sunset. "Redness" itself isn't a physical object, yet it's a property shared by countless individual items. Other examples include "humanity" (shared by all humans), "justice" (an ideal applicable to many actions or systems), or "triangularity" (shared by all triangles). The question is: Where does "redness" exist, if not in any single red thing? -

The Elusive Particular

A Particular is an individual, concrete entity that exists in a specific place and time. My coffee mug, the cat currently sleeping on my lap, or the specific thought I'm having right now – these are all particulars. They instantiate universals (e.g., the mug instantiates "mugness" and "whiteness"), but they are distinct, unique existences. -

Why Metaphysics Cares

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality, including the relationship between mind and matter, between substance and attribute, and between potentiality and actuality. The debate over universals strikes at the heart of this. If universals exist independently, then reality is structured in a certain way, perhaps with an ideal realm. If they are merely mental, then our minds play a much more active role in constituting reality. And if they are just names, then our language might be more arbitrary than we think.

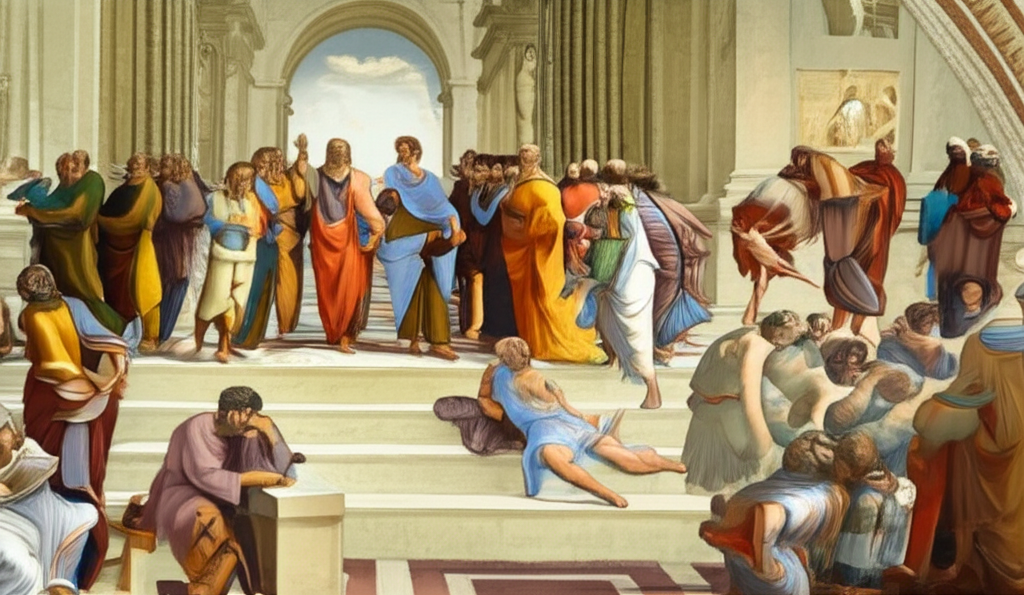

From Ancient Greece to Medieval Debates: Tracing the Idea of Form

The discussion about Universal Ideas is not new; it's a cornerstone of Western philosophy, deeply explored in the Great Books of the Western World.

Plato's Realm of Forms: Ideas as Archetypes

For Plato, as articulated in works like The Republic and Phaedo, Universal Ideas — which he called Forms — possess the highest degree of reality. These Forms are:

- Transcendent: They exist independently of the physical world, in a separate, non-spatial, non-temporal realm.

- Perfect and Unchanging: Unlike the imperfect, fleeting particulars we perceive, the Form of Beauty or Justice is eternally perfect.

- Archetypal: Particulars in our world are mere imperfect copies or participants in these perfect Forms. A beautiful flower is beautiful because it "participates" in the Form of Beauty.

- Knowable through Reason: We cannot grasp the Forms through our senses, but only through intellect and philosophical contemplation.

For Plato, the Metaphysical status of a Universal Idea like "equality" is that it is a real, independently existing entity, more real than any two equal sticks we might ever encounter.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Universals Within Particulars

Aristotle, Plato's student, offered a different perspective, challenging the separation of Form from matter. For Aristotle, as seen in Metaphysics and Categories:

- Immanent: Forms (universals) do not exist in a separate realm but are in the Particular things themselves. The "humanity" of a human being is inseparable from that human being.

- Essence: The Form of a thing is its essence, that which makes it what it is. It's the structure or organization of matter.

- Abstracted by the Mind: While universals exist in particulars, our minds can abstract them, allowing us to form general concepts. We see many individual humans and then form the Idea of "humanity."

Aristotle's view grants Universal Ideas a Metaphysical status as real, but not independently existing entities. They are real as characteristics or essences instantiated in the world of particulars.

The Medieval Conundrum: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The medieval period inherited this debate, leading to a rich and complex discussion about the Metaphysical status of Universal Ideas. This period saw the rise of three main positions:

-

Realism:

- Description: Echoing Plato (though often in Christianized forms), realists argued that Universals are real, independently existing entities, either as transcendent Forms (Platonic Realism) or as properties inherent in particulars (Aristotelian Realism).

- Proponents: Anselm of Canterbury, Thomas Aquinas (moderated realist).

- Implication: Our concepts correspond to something objectively real in the world.

-

Nominalism:

- Description: This radical view argued that Universals are nothing more than names (nomina in Latin) or labels we apply to groups of similar Particulars. There is no "humanity" existing separately from individual humans; there are only individual humans, and we call them all "human."

- Proponents: William of Ockham, Roscelin.

- Implication: Only particulars exist. Universal concepts are mere linguistic conveniences, a product of human thought and language, lacking any independent Metaphysical status.

-

Conceptualism:

- Description: A middle ground, conceptualists argued that Universals exist, but only as concepts in the mind. They are not independent entities in the world (against realism) nor are they mere names (against nominalism). Our minds have the capacity to form general Ideas based on similarities observed in Particulars.

- Proponents: Peter Abelard, John Locke.

- Implication: Universals have a Metaphysical status as real mental constructs, derived from and applicable to the external world, but not existing outside the mind.

Why Does It Matter? The Ramifications of Universal Ideas

The debate over the Metaphysical status of Universal Ideas isn't just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for how we understand reality, knowledge, and even our moral lives.

- Science and Classification: How do we categorize the natural world? If "species" are merely names, does biological classification lose its objective basis? If universals are real, then our scientific categories might reflect genuine divisions in nature.

- Ethics and Moral Principles: Are concepts like "justice," "goodness," or "human rights" merely cultural constructs or subjective opinions? Or do they point to objective, Universal Ideas that hold true regardless of individual belief? The answer profoundly impacts the foundation of our ethical systems.

- Language and Thought: How do we communicate? When I say "tree," how do you understand me if there's no shared Universal Idea of a tree? The existence and nature of universals impact our understanding of how language refers to the world and how we form coherent thoughts.

The Unfolding Dialogue

The question of "The Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas" remains a vibrant area of philosophical inquiry. While the specific terms and arguments have evolved since the time of Plato and Aristotle, the core tension persists: how do we reconcile the singular, unique experiences of Particulars with the general, abstract concepts that seem indispensable to our thought and language? Whether we lean towards the robust reality of Forms, the immanence of essences, or the mental constructs of conceptualism, our answer shapes the very foundation of our philosophical worldview, reminding us that sometimes the most abstract Ideas have the most concrete consequences.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms Explained""

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Nominalism vs Realism Philosophy""