The Enduring Enigma: Unpacking the Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas

The question of "universals" stands as one of philosophy's most persistent and profound metaphysical puzzles. At its heart, it asks: what is the nature of shared properties, concepts, and categories that apply to multiple individual things? Do "redness," "humanity," or "triangularity" exist independently of the particular red objects, individual humans, or specific triangles we encounter? This article delves into the historical and ongoing debate, exploring various philosophical answers to the question of whether these universal Ideas possess a genuine metaphysical reality, examining their relationship to the particular objects of our experience and the concept of Form.

Setting the Stage: What Exactly Are We Talking About? Universal and Particular

Before we dive into the grand philosophical debates, let's clarify our terms.

- Particulars: These are the individual, concrete, unique things we perceive in the world. My specific coffee cup, that particular oak tree, your unique laugh. They exist in a specific time and place.

- Universals: These are the properties, qualities, relations, or types that can be instantiated by multiple particulars. "Coffee cup-ness," "oak tree-ness," "laugh-ness." They are general concepts that apply to many individual instances.

The core metaphysical challenge is to explain the relationship between these two. How can many distinct particulars share the same universal property? Does this shared property exist somewhere? And if so, where and how?

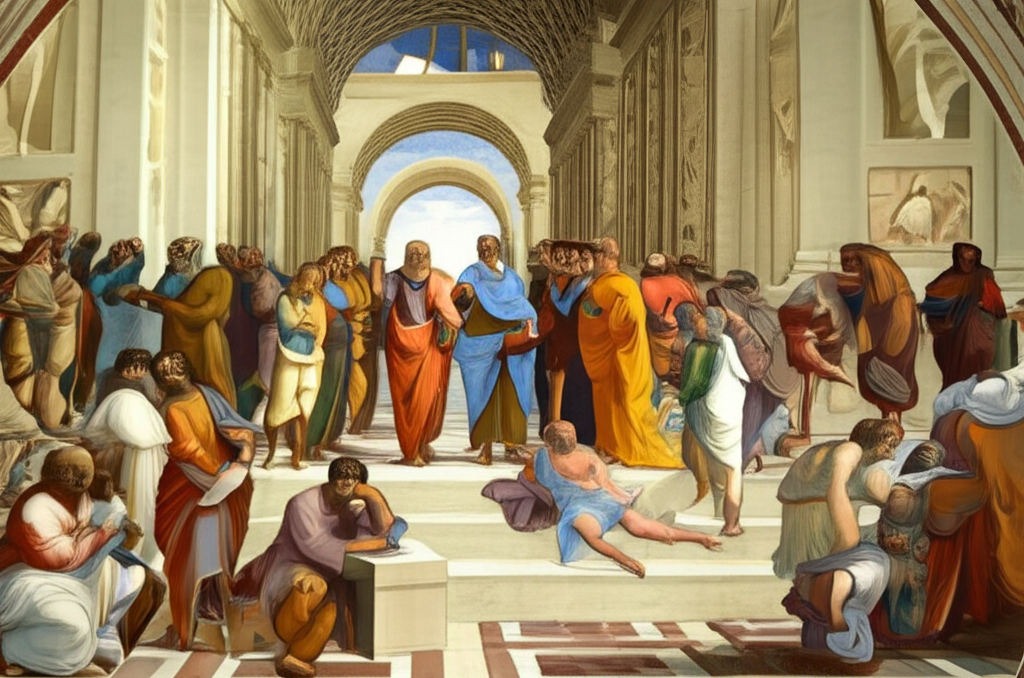

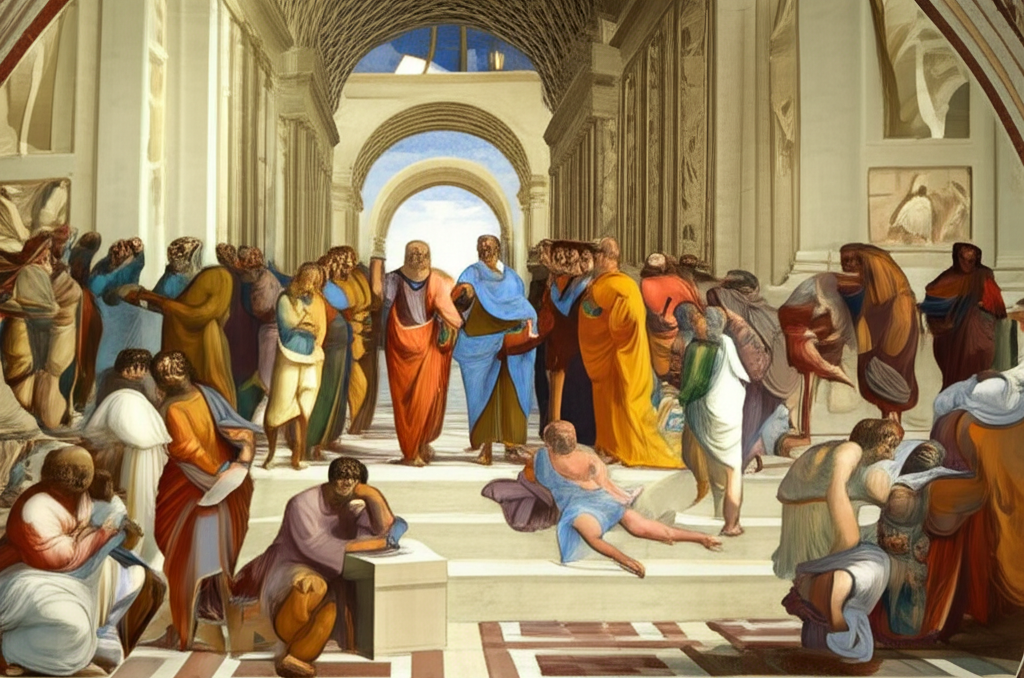

Plato's Enduring Forms: Ideas Beyond Our World

Perhaps the most famous and influential answer comes from Plato, heavily featured in the Great Books of the Western World. For Plato, universal Ideas, which he called Forms, possess the highest degree of reality. These Forms are:

- Transcendent: They exist independently of the physical world, in a separate, non-physical realm.

- Perfect and Immutable: Unlike the imperfect and changing particulars we perceive, Forms are eternal and unchanging.

- Archetypes: Particular objects are merely imperfect copies or participations in these perfect Forms. A beautiful flower is beautiful because it participates in the Form of Beauty.

For Plato, the Form of "Humanity" is more real than any individual human, providing the very blueprint for what it means to be human. Our minds, through reason, can access these Forms, which are the true objects of knowledge. This view is a classic example of Platonic Realism.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Universals in the Particular

Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, offered a significant counterpoint, shifting the metaphysical locus of Forms. While Aristotle agreed that universals are real and necessary for knowledge, he rejected the notion of a separate realm of Forms. For Aristotle, the Form of a thing is not transcendent but immanent – it exists within the particular object itself.

Consider a table. For Aristotle:

- The Form of "table-ness" is the structure, function, and essence that makes a table a table.

- This Form is inseparable from the matter of the table (wood, metal, etc.).

- It is through abstracting from many particular tables that our minds grasp the universal Form of "table-ness."

Aristotle's view suggests that universals are not prior to particulars in existence, but rather co-exist with them. We understand universals by observing and categorizing particulars. This perspective is often termed Aristotelian Realism or Immanent Realism.

The Medieval Divide: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The debate over universals raged throughout the Middle Ages, with scholastic philosophers building upon and challenging the foundations laid by Plato and Aristotle. This era saw the emergence of distinct schools of thought:

| Philosophical Stance | Description | Key Idea Regarding Universals |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Realism | Aligned with Plato, universals exist independently of and prior to particulars. They are real entities in their own right, even if unperceived. | Universalia ante rem (Universals before things) |

| Moderate Realism | Aligned with Aristotle, universals exist within particulars. They are real, but only as instantiated in individual things, not separately. Our minds abstract them from particulars. | Universalia in re (Universals in things) |

| Nominalism | Universals are not real entities at all. They are merely names, labels, or linguistic conventions that we apply to groups of similar particulars. There is no shared "humanity" beyond the word "human." | Universalia post rem (Universals after things) – only as mental constructs or words. |

| Conceptualism | A middle ground between moderate realism and nominalism. Universals exist, but only as concepts in the mind. They are not independent realities (like Plato's Forms) nor mere words (like nominalism), but mental constructs formed by observing similarities. | Universalia post rem (Universals after things) – as concepts formed by the mind, but with a basis in observed similarities among particulars. |

This rich tapestry of thought highlights the persistent difficulty in assigning a definitive metaphysical status to these shared Ideas.

The Modern Perspective: Ideas in the Mind

With the rise of empiricism and rationalism in the modern era, the focus often shifted from the external existence of universals to their status in the human mind. Thinkers like John Locke and David Hume, while acknowledging our ability to form general Ideas, often questioned their independent reality. For empiricists, our general concepts are derived from sense experience, built up from repeated observations of similar particulars. They are mental constructs, not external entities.

Immanuel Kant, in his transcendental idealism, offered a different synthesis. He argued that while our knowledge begins with experience, the mind itself imposes universal categories and structures (like causality, substance, and unity) upon that experience. These are not external Forms, nor are they merely arbitrary names; they are necessary conditions for our understanding of the world.

Why Does This Matter? The Enduring Metaphysical Puzzle

The debate over the metaphysical status of universal Ideas is not just an arcane philosophical exercise. It has profound implications for:

- Epistemology (Theory of Knowledge): If universals are real, how do we know them? If they are merely mental constructs, what does that say about the objectivity of our knowledge?

- Ethics: Is there a universal "Good" or "Justice," or are these merely cultural conventions?

- Science: Do scientific laws describe universal truths about reality, or are they convenient models for predicting phenomena?

- Language: How does language, which relies heavily on general terms, relate to reality?

The search for the true nature of the universal continues to animate philosophical inquiry, reminding us that even the most common Ideas can conceal deep and fascinating metaphysical mysteries. Whether they are transcendent Forms, immanent essences, or mere names, their role in shaping our understanding of the world is undeniable.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Problem of Universals Explained""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms vs Aristotle's Metaphysics""