The Enduring Enigma: Unpacking the Metaphysical Status of Universal Ideas

Have you ever stopped to ponder the nature of "redness" itself, or "humanity," or "justice"? Not a specific red apple, or a particular human being, or a single act of justice, but the idea that binds them all together? This seemingly abstract question lies at the heart of one of philosophy's most profound and enduring debates: the metaphysical status of universal ideas. This article dives into the core of this discussion, exploring whether these shared qualities exist independently, as mental constructs, or merely as linguistic conveniences. It's a journey into Metaphysics, challenging our assumptions about the very fabric of reality and the relationship between our minds and the world.

What are Universals and Particulars?

Before we can unravel their metaphysical status, we must first distinguish between the universal and the particular.

- Particulars are the individual, concrete things we encounter in our everyday lives: this specific chair, that unique dog, the distinct thought you are having right now. They are singular, existing in a specific time and place.

- Universals, on the other hand, are the qualities, properties, or relations that can be instantiated by multiple particulars. Think of "chair-ness," "dog-ness," or "thought-ness." They are general concepts that apply across many individual instances.

The core philosophical problem arises when we ask: What is the nature of these universals? Do they exist in the same way particulars do, or in a different way altogether? This question is not just semantic; it touches upon the fundamental nature of reality, knowledge, and language itself.

The Great Debate: Tracing the Metaphysical Lineage of Ideas

The history of philosophy is rife with attempts to grapple with the status of universals. From ancient Greece to the present day, thinkers have proposed vastly different answers, each with profound implications for our understanding of reality.

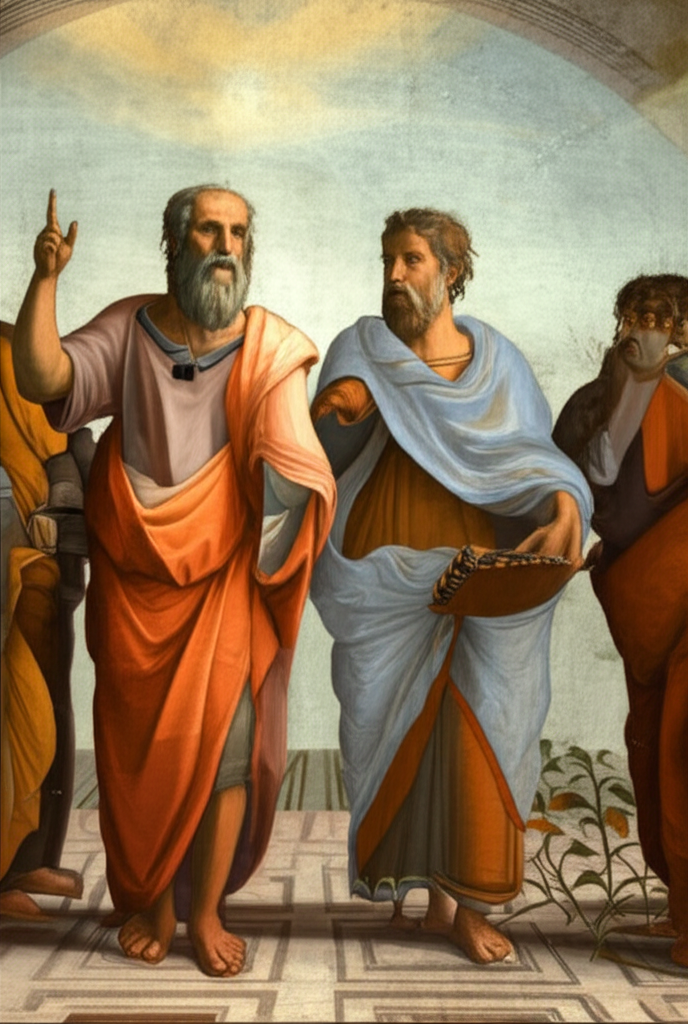

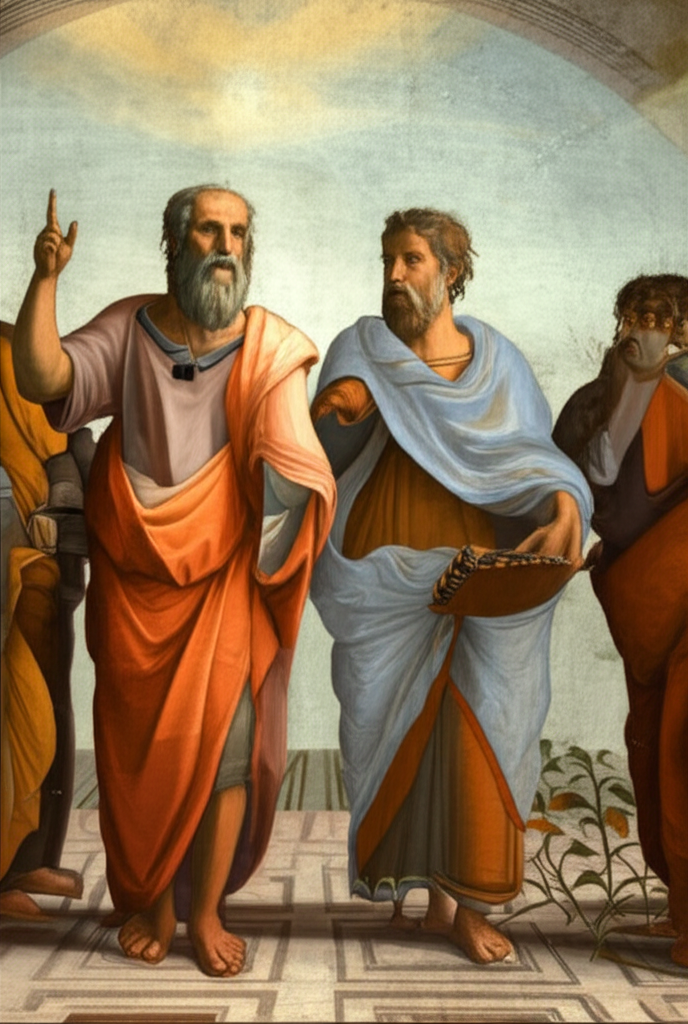

Plato's Realm of Forms: Universals as Independent Realities

Perhaps the most famous and influential answer comes from Plato, as articulated in his works like The Republic and Parmenides, foundational texts in the Great Books of the Western World. For Plato, universals are not mere concepts or names; they are eternal, unchanging, and perfect Forms (or Ideas) that exist independently of the physical world.

- Key Tenets of Platonic Realism:

- Transcendent Existence: The Form of Beauty, for instance, exists in a separate, non-physical realm, distinct from any beautiful object we perceive.

- Perfection and Immutability: These Forms are perfect archetypes, and all particular beautiful things are merely imperfect copies or participants in the Form of Beauty.

- Epistemological Significance: True knowledge (episteme) is knowledge of these Forms, accessed not through the senses, but through reason and intellect. Our sensory world is merely a shadow of this ultimate reality.

For Plato, the Idea of a circle is more real than any circle drawn on a blackboard, because the blackboard circle is imperfect and temporary, while the Form of a circle is perfect and eternal. This perspective firmly places universals as having a robust, independent metaphysical status.

Aristotle's Immanent Universals: Forms Within Particulars

Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, offered a significant counter-argument. While acknowledging the reality of universals, Aristotle (whose works like Metaphysics and Categories are also cornerstones of the Great Books) rejected the notion of a separate realm of Forms.

- Key Tenets of Aristotelian Realism:

- Immanent Existence: Universals, or Forms, do not exist apart from particular things. Instead, they are immanent within them. The "redness" of an apple exists in that specific apple, not in some abstract "Redness" realm.

- No Separate Realm: There is no separate world of Forms; reality is found in the concrete, individual substances we experience.

- Abstracted by the Mind: Our minds abstract universals from observing many particulars. By seeing many red things, we form the idea of redness. However, this mental idea reflects a real commonality existing in the world.

For Aristotle, the Form of "humanity" is truly present in every human being. It is through studying particular humans that we come to understand what "humanity" truly is. This view still grants universals a real metaphysical status, but one that is intrinsically tied to the particulars themselves.

Medieval Philosophy: Nominalism and Conceptualism

The debate continued fiercely through the Middle Ages, with philosophers like William of Ockham challenging the realist positions of Plato and Aristotle.

- Nominalism: This view asserts that universals are merely names or labels (nomina) that we apply to groups of similar particulars. There is no underlying commonality in reality that corresponds to the universal term. "Redness" is just the word we use for all things that happen to look red; there is no shared "redness" existing either transcendentally or immanently. For nominalists, only particulars exist. The idea of a universal is simply a linguistic tool.

- Conceptualism: A middle ground, conceptualism argues that universals exist as concepts or mental ideas within the human mind. They are not independent realities in the world (as realists would argue), nor are they mere names (as nominalists would claim). Instead, they are mental constructs formed by abstracting common features from particulars. The idea of "humanity" exists in our minds as a concept, allowing us to categorize and understand the world, but it doesn't have an external, independent existence.

Here's a simplified comparison of these major positions:

| Philosophical Position | Metaphysical Status of Universals (Ideas/Forms) | Primary Mode of Existence | Key Proponents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platonic Realism | Real, independent, and transcendent | Separate realm of Forms | Plato |

| Aristotelian Realism | Real, inherent in particulars (immanent) | Within individual things | Aristotle |

| Conceptualism | Real, but only as mental concepts | In the human mind | Peter Abelard |

| Nominalism | Not real; merely names or linguistic labels | As words or conventions | William of Ockham |

Why Does It Matter? The Enduring Relevance of Universals

The debate over the metaphysical status of universal ideas isn't just an academic exercise. Its implications ripple through various fields:

- Science: How do scientific laws, which describe universal regularities, relate to the particulars they govern? Do "laws of nature" exist independently, or are they human constructs?

- Ethics: If "justice" or "goodness" are merely names or subjective concepts, what objective basis do we have for moral claims? If they are real Forms, then objective morality seems more plausible.

- Logic and Mathematics: The universal truths of mathematics (e.g., 2+2=4) seem to hold independently of any particular instances. What is their ultimate nature?

- Language: How do words, which are universals, refer to particulars? What gives them their meaning?

The question of how our minds grasp and categorize the world, and whether these categories correspond to something truly existing beyond our minds, remains a central philosophical challenge.

Further Exploration

The journey into the metaphysical status of universal ideas is a deep dive into the very nature of reality. It compels us to question what we perceive, what we know, and how language shapes our understanding. Whether you lean towards the eternal Forms of Plato, the immanent Forms of Aristotle, or the more pragmatic views of nominalism or conceptualism, engaging with this debate enriches your philosophical perspective.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Problem of Universals Explained Philosophy""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms vs Aristotle's Metaphysics""