The Unseen Threads of Reality: Unpacking the Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms

What makes a red apple red? What do all circles have in common, regardless of their size or whether they're drawn in sand or on a screen? This seemingly simple question plunges us headfirst into one of philosophy's most profound and persistent debates: the metaphysical status of universal forms. At its heart, we're asking whether concepts like "redness," "humanness," or "circularity" exist independently of the individual things that embody them, and if so, what kind of existence that is. This isn't just an abstract intellectual exercise; how we answer shapes our understanding of reality, knowledge, and even language itself.

What's a "Universal" Anyway? Differentiating the Abstract from the Concrete

Before we dive into the philosophical fray, let's clarify our terms. In metaphysics, we often distinguish between universals and particulars.

- Particulars: These are the individual, concrete things we encounter in the world. This specific red apple, that particular human being named Socrates, the circle I just drew on a napkin. They are unique, located in space and time, and subject to change.

- Universals: These are the qualities, properties, or relations that multiple particulars can share. "Redness" is a universal because many different apples, cars, and sunsets can be red. "Humanness" is a universal shared by all human beings. "Circular" describes countless individual shapes.

The core metaphysical question isn't whether we think about universals – clearly, we do. It's whether these universals exist objectively in some sense, independently of our minds and the particulars that instantiate them, or if they are merely mental constructs or convenient labels. Do they have a "being" of their own?

Plato's Enduring Forms: A Realm Beyond Our Senses

For many, the journey into the metaphysical status of universal forms begins with Plato. For him, universals – which he called Forms (or Ideas, often used interchangeably in this context) – possessed a far more robust and fundamental reality than the fleeting particulars we perceive with our senses.

Plato posited a World of Forms, a transcendent realm existing independently of the physical world. In this realm reside the perfect, eternal, and unchanging archetypes of everything we encounter.

- The Form of Beauty is perfect beauty itself, not merely a beautiful person or painting.

- The Form of Justice is absolute justice, unblemished by political compromise or individual bias.

- The Form of the Good is the ultimate source of all truth and being.

Platonic Forms: Key Metaphysical Characteristics

- Separate Existence: They exist independently of the physical world and our minds.

- Eternal and Unchanging: Unlike particulars, Forms are not born and do not perish; they are timeless.

- Perfect and Archetypal: They are the ideal blueprints, the ultimate standards against which particulars are measured.

- Intelligible, Not Sensible: We grasp Forms through reason and intellect, not through sensory experience.

- Causative: Particulars "participate" in or "imitate" the Forms, deriving their nature and existence from them. A beautiful flower is beautiful because it participates in the Form of Beauty.

For Plato, the metaphysical status of these Forms is paramount. They are more real than the particulars. The individual red apple is merely a pale reflection of the perfect Form of Redness. This view, often called Platonic Realism, asserts that universals are truly real, objective entities.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Reality Within the Particular

Aristotle, Plato's most brilliant student, famously broke with his teacher on the separation of Forms. While he agreed that universals were real and that there was an underlying structure to reality, he rejected the notion of a separate World of Forms. For Aristotle, the Form of a thing is not transcendent but immanent; it exists within the particular object itself.

Consider a statue. For Plato, the Form of the Human exists separately, and the sculptor tries to imitate it. For Aristotle, the Form (or essence) of "human" is what makes an individual human being human. It's not in another realm; it's intrinsically tied to the particular matter that constitutes the human.

Aristotelian Forms: Key Metaphysical Characteristics

- Immanent Existence: Forms exist in particulars, not separate from them. They are the essential nature of things.

- Inseparable from Matter: A Form cannot exist without being instantiated in some matter, just as matter cannot exist without some Form (except for prime matter, which is pure potentiality). This is his hylomorphic theory (matter + form).

- Known Through Experience: We come to understand universals by abstracting them from our sensory experience of many particulars. By observing many individual humans, we grasp the universal Form of "humanity."

- Organizing Principle: The Form provides the structure and purpose of a particular thing.

For Aristotle, the metaphysical status of universals is that they are real, but their reality is tied to the existence of particulars. There is no "redness" floating around independently; there are only red things, and from these, our intellect abstracts the concept of redness. This is a form of Immanent Realism or Moderate Realism.

The Medieval Echoes: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The debate over the metaphysical status of universal forms continued to rage throughout the Middle Ages, with theologians and philosophers grappling with its implications for theology, logic, and the nature of knowledge. Three main positions emerged:

| Position | Description Form and is very much a part of the particular thing.

## The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms: An Enduring Inquiry

The question of how "things of the same kind" can be alike has fascinated thinkers for millennia. From the redness of an apple to the courage of a hero, we intuitively group and categorize. But what is the nature of that shared "kindness" or property? Does "redness" exist independently of all red things, or is it merely an abstract concept in our minds? This is the core of the metaphysical debate surrounding universal forms, a philosophical puzzle that probes the very fabric of reality, challenging our understanding of what is fundamentally real and how we come to know it. This article will explore the historical roots of this inquiry, focusing on the contrasting views of Plato and Aristotle, and touch upon its enduring relevance.

What is a Universal? Distinguishing Kinds from Individuals

To grasp the metaphysical challenge, we must first understand the distinction between universals and particulars.

- Particulars: These are the individual, concrete objects we experience in the world. This specific tree outside my window, that unique human named Socrates, the particular sensation of warmth I feel right now. Particulars exist at a specific point in space and time, are unique, and are subject to change.

- Universals: These are the properties, qualities, relations, or kinds that can be instantiated by multiple particulars. "Treeness" is a universal shared by all trees. "Humanness" is a universal shared by all humans. "Warmth" is a universal that can be felt by many. "Being taller than" is a universal relation.

The central metaphysical question is: Do these universals exist objectively, independently of the particular things that exemplify them, or are they merely mental constructs, names, or abstractions? What is their mode of being?

Plato's Realm of Forms: The Archetypes of Reality

For Plato, the answer was unequivocally that universals – which he famously called Forms (or Ideas) – possess a robust, independent, and ultimately more real existence than the fleeting particulars we perceive with our senses. He posited a transcendent, non-physical realm: the World of Forms.

In this realm, reside the perfect, eternal, and unchanging blueprints or archetypes of everything we encounter in the physical world.

- The Form of Beauty is not merely a beautiful face or sunset; it is Beauty Itself, perfect and absolute.

- The Form of Justice is the essence of justice, untainted by human error or societal variation.

- The Form of the Good is the ultimate source of all truth, being, and value.

Key Metaphysical Characteristics of Platonic Forms:

- Separate and Transcendent: They exist independently of the physical world and our minds, in a realm accessible only through intellect.

- Eternal and Unchanging: Unlike particulars which are born and perish, Forms are timeless, immutable, and imperishable.

- Perfect and Archetypal: They are the ideal standards, the ultimate models that particulars imperfectly copy or "participate" in.

- Intelligible, Not Sensible: We grasp Forms through reason and philosophical contemplation, not through sensory experience. Our senses only show us imperfect copies.

- Causative: Particulars derive their nature, identity, and intelligibility from their participation in the Forms. A chair is a chair because it partakes in the Form of Chairness.

For Plato, the metaphysical status of these Forms is supreme. They are the ultimate reality, providing the underlying structure and intelligibility of the cosmos. Our physical world is merely a shadow play, a collection of imperfect copies of these perfect Ideas. This view is a classic example of Platonic Realism or Extreme Realism.

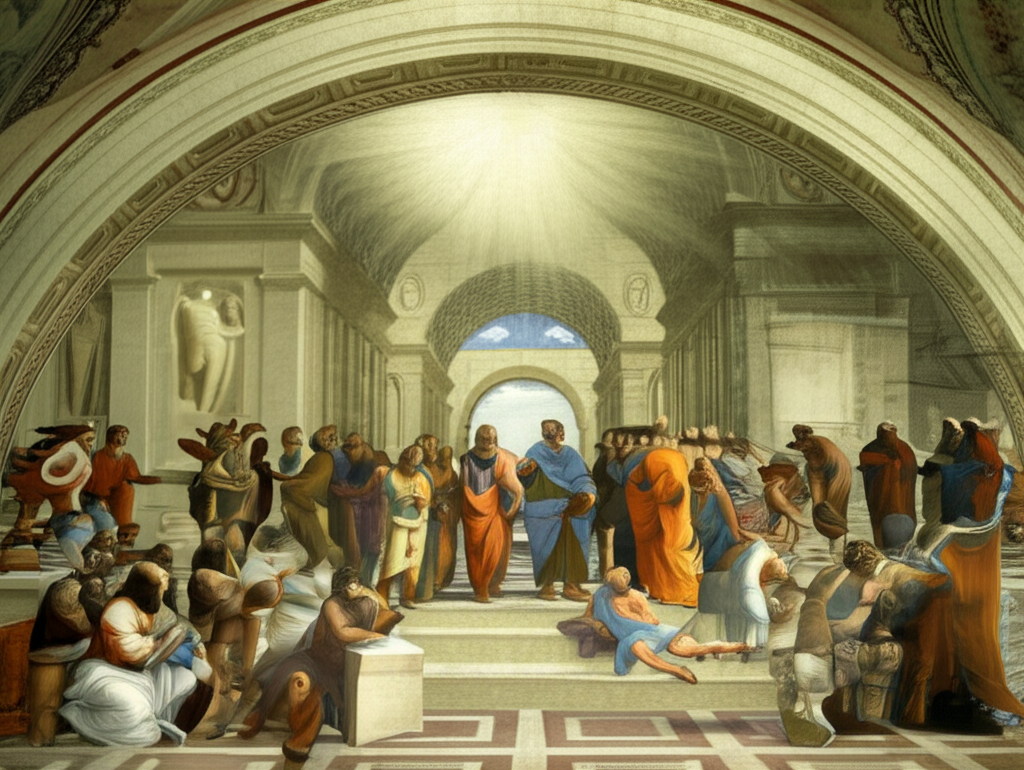

(Image: A classical Greek fresco depicting Plato and Aristotle engaged in debate. Plato, with an older, bearded appearance, points a finger decisively upwards towards the heavens, symbolizing his theory of transcendent Forms. Aristotle, younger and with a more grounded posture, extends his hand horizontally towards the earth, representing his focus on empirical observation and the immanent reality within the physical world. The background suggests an ancient Athenian academy, with architectural elements and other figures observing.)

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: The Essence Within Particulars

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a profound critique of his teacher's theory of separated Forms. While agreeing that universals are real and essential for knowledge, he rejected the notion that they exist in a separate, transcendent realm. For Aristotle, the Form (or essence) of a thing is not outside the particular but within it, intrinsically bound to its matter.

Consider a bronze statue. For Plato, the Form of the Human exists separately, and the bronze is merely matter shaped to imitate it. For Aristotle, the Form of "human" is what makes this specific statue human-shaped; it's the organizing principle that gives the matter its specific identity and function. The Form is what makes a thing what it is.

Key Metaphysical Characteristics of Aristotelian Forms:

- Immanent Existence: Forms exist in particulars, as their essential nature. They are not separate from the physical world.

- Inseparable from Matter: A Form cannot exist without being instantiated in some matter, just as matter cannot exist without some Form (except for prime matter, which is pure potentiality). This is his famous hylomorphic theory, where every substance is a composite of matter and form.

- Known Through Abstraction: We come to understand universals by observing many particulars and abstracting the common features or essences through our intellect. We don't recall them from a prior existence, as Plato suggested.

- Organizing Principle: The Form provides the structure, function, and purpose (telos) of a particular thing. It

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms philosophy"