The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms: An Enduring Philosophical Inquiry

Summary: The metaphysical status of Universal Forms stands as one of philosophy's most profound and enduring questions, fundamentally shaping our understanding of reality, knowledge, and language. At its core, the debate asks: Do universals exist? And if so, what kind of existence do they have? Are they transcendent, perfect blueprints (Plato's Ideas) existing independently of the physical world, or are they immanent essences found within particular objects (Aristotle's Forms)? This article delves into the historical lineage of this essential Metaphysics problem, exploring the arguments for and against the independent existence of these abstract entities that allow us to categorize, understand, and communicate about the world around us. From ancient Greek thought to modern philosophy, the Universal and Particular distinction remains a crucible for philosophical inquiry.

Unveiling the Problem: What Are Universals?

Before we can discuss their metaphysical status, we must first clarify what we mean by "universals." Consider the concept of "redness" or "justice." We encounter many red objects—a ripe apple, a stop sign, a sunset—and many just acts. What makes them all "red" or "just"? Is there a shared quality, an underlying Form or Idea, that all these particulars participate in or instantiate? This shared quality, which can be predicated of many individual things, is what philosophers refer to as a universal.

The problem then unfolds:

- Existence: Do these universals truly exist, or are they merely convenient labels we impose on collections of similar things?

- Nature: If they exist, what is their nature? Are they concrete or abstract? Mind-dependent or mind-independent?

- Location: Where do they exist? In a separate realm, within particulars, or only in our minds?

- Relationship to Particulars: How do universals relate to the individual, concrete objects we experience?

This foundational inquiry into Metaphysics dictates much of our epistemology and even our ethics.

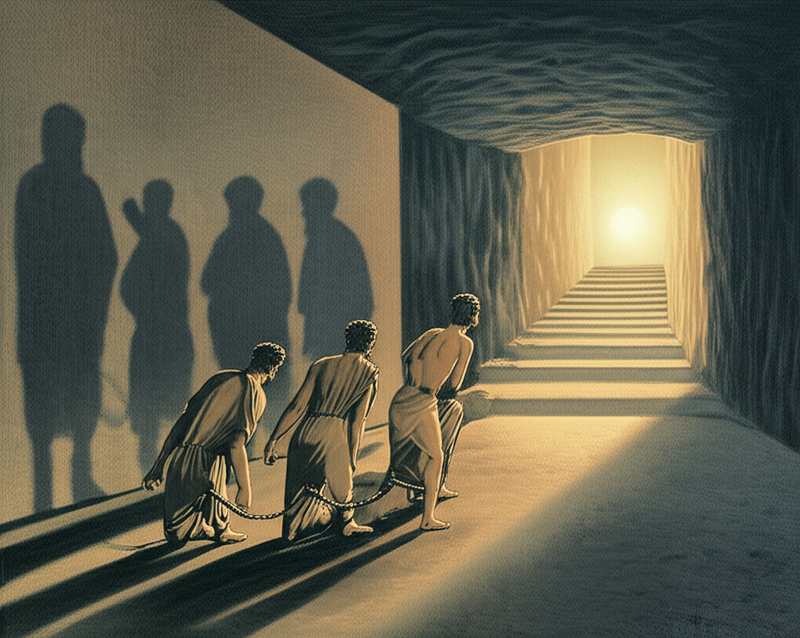

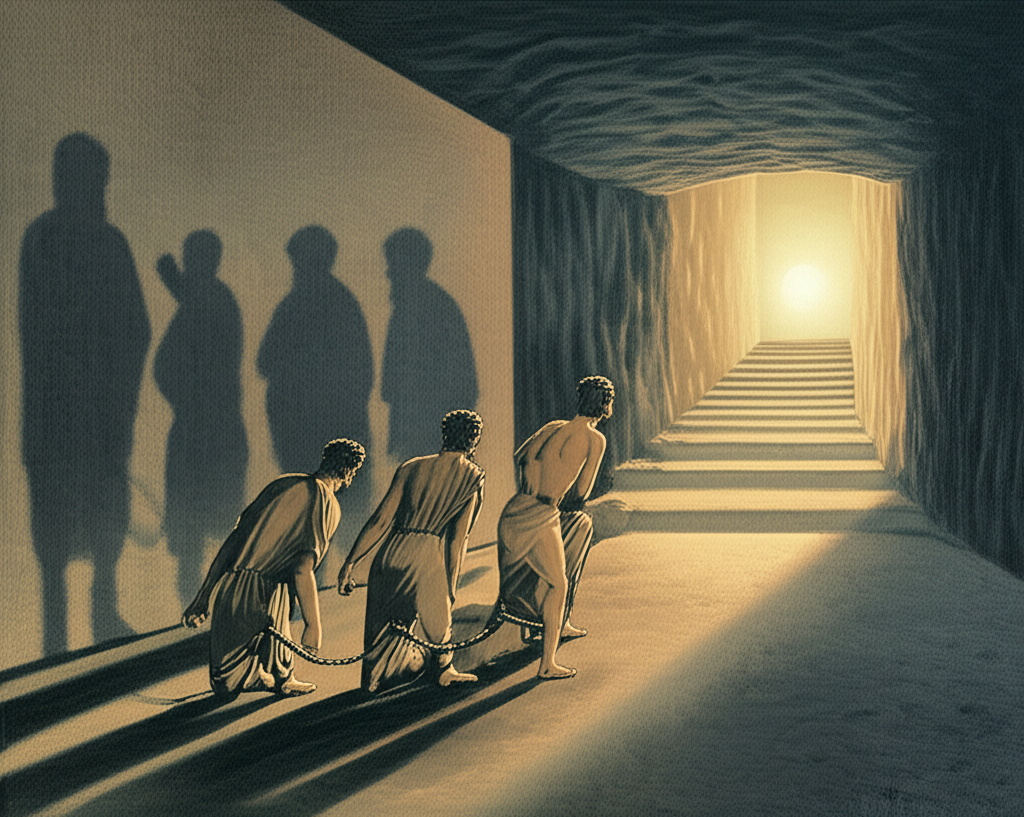

Plato's Transcendent Forms: The Realm of Pure Ideas

Perhaps the most iconic answer to the problem of universals comes from Plato, extensively explored in the Great Books of the Western World such as The Republic, Phaedo, and Parmenides. For Plato, universals, which he called Forms (or Ideas), possess the highest degree of reality. They are:

- Transcendent: Existing independently of the physical world, in a non-spatial, non-temporal realm accessible only through intellect, not the senses.

- Perfect and Immutable: Unchanging, eternal, and flawless. The Form of Beauty is perfect beauty itself, unlike any beautiful object in the sensory world, which is always imperfect and fleeting.

- Paradigmatic: They serve as the perfect blueprints or archetypes for all the particular things we perceive. A particular chair is a chair because it "participates" in or "imitates" the Form of Chair.

- Objects of Knowledge: True knowledge (episteme) can only be of the Forms, as they are stable and eternal. Sensory experience provides only opinion (doxa).

Plato's Forms provide a powerful explanation for how we can have objective knowledge, how language works (we use general terms like "dog" or "justice" that refer to something beyond any single instance), and why there's order and intelligibility in the world. The Form of "Good" even serves as the ultimate source of all being and knowledge.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Universals in Particulars

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a significant departure from his teacher's transcendent realm. While acknowledging the existence of Forms as the essences of things, Aristotle argued vehemently against their separate existence. For Aristotle, as detailed in Metaphysics and Categories from the Great Books, the Form of a thing is inseparable from its matter; it exists within the particular object itself.

Consider the following comparison:

| Feature | Plato's Forms (Transcendent Realism) | Aristotle's Forms (Immanent Realism) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Separate, non-physical realm | Inherent in the particular object |

| Existence | Independent of particulars | Dependent on particulars for their existence |

| Reality | More real than particulars (archetypes) | Constitutive of particulars (essence) |

| Acquisition | Recollection (anamnesis) / Intellectual grasp | Abstraction from sensory experience |

| Example | The Form of Horse exists apart from all horses | The Form of Horse exists in every horse |

For Aristotle, the Form is the "what-it-is" of a thing, its essence or nature. It is what makes a particular oak tree an oak tree, and not a pine. These Forms are discovered through empirical observation and abstraction, not through access to a separate realm. The universal "humanity" exists in individual humans, not in some celestial sphere. This view grounds universals firmly within the natural world, making Metaphysics an inquiry into the fundamental structures of observable reality.

The Medieval Debates: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The debate over the metaphysical status of universals continued with fervor throughout the medieval period, becoming known as "the problem of universals." This period, too, drew heavily from the Great Books, particularly the rediscovered works of Aristotle and the ongoing engagement with Platonic thought (often via Neoplatonism).

- Realism (Platonic/Moderate):

- Extreme Realism (Platonic): Universals exist independently of particulars and the human mind (e.g., Anselm).

- Moderate Realism (Aristotelian): Universals exist in particulars as their essences, but can be abstracted by the mind (e.g., Thomas Aquinas).

- Nominalism: Universals are merely names or labels we apply to collections of similar things. They have no independent existence outside the mind. There is no Form of "redness" existing anywhere; there are just many red things, and we call them all "red" (e.g., William of Ockham).

- Conceptualism: Universals exist as concepts in the human mind. They are not independent entities in the world, nor are they mere names; they are mental constructs that allow us to organize and understand our experiences (e.g., Peter Abelard).

These debates had profound implications, particularly for theology (e.g., the nature of God, the Trinity, original sin) and epistemology (how we acquire knowledge). Nominalism, for instance, often led to a focus on empirical observation and a skepticism towards abstract metaphysical entities, paving the way for later scientific thought.

The Enduring Question in Modern Thought

While the specific terminology and frameworks have evolved, the core problem of the metaphysical status of universals continues to resonate in contemporary philosophy.

- Philosophy of Language: How do general terms ("cat," "justice") acquire meaning? Do they refer to universals, or are they mere linguistic conventions?

- Philosophy of Mind: Are concepts in our minds universals? How do we form general ideas from particular experiences?

- Metaphysics of Properties: Are properties (like "being red" or "being heavy") universals? If so, what is their nature and how do they relate to the objects that possess them?

- Mathematics and Logic: Do mathematical entities (numbers, sets) exist as universals?

The debate over Form and Idea, Universal and Particular, remains a vibrant and essential area of philosophical inquiry. Our position on this fundamental question profoundly shapes our entire philosophical worldview, influencing everything from our theory of knowledge to our understanding of the very fabric of reality. The Metaphysics of universals is not just an ancient curiosity; it is a living, breathing challenge to our deepest assumptions about existence itself.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Forms Theory Explained"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Metaphysics Universals"