Unveiling the Enduring Reality: The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms

Summary: The question of the metaphysical status of universal forms stands as one of philosophy's most profound and enduring inquiries, directly impacting our understanding of reality, knowledge, and language. At its heart lies the distinction between the universal—concepts, properties, or types (e.g., "humanity," "redness," "justice")—and the particular—individual instances of those concepts (e.g., this person, that red apple, this specific act of justice). This article delves into the historical philosophical debate concerning whether these universals exist independently, as transcendent archetypes, or merely as immanent properties, mental constructs, or even just names. We explore the seminal contributions of Plato, Aristotle, and later medieval thinkers, examining how their differing views on Form and Idea have shaped the very landscape of metaphysics.

The Enduring Riddle: Universal and Particular

From the earliest philosophical stirrings, humanity has grappled with the perplexing relationship between the general and the specific. We observe countless individual instances of "red," yet we speak of "redness" as if it were a singular, unified concept. We encounter myriad individual "trees," but our minds grasp the universal concept of "tree-ness." The core metaphysical challenge, then, is to determine the nature of these universals. Do they possess an existence independent of the individual particulars that exemplify them? Or are they merely convenient labels, mental abstractions, or properties inextricably bound to the physical world?

This fundamental distinction between the universal and particular underpins much of Western philosophy. It's not merely an academic exercise; our answer to this question profoundly influences our theories of knowledge, ethics, and even the nature of scientific classification. The search for the true metaphysical status of these overarching concepts has driven thinkers for millennia, from the ancient Greeks to contemporary analytic philosophers.

Plato's Realm of Forms: The Archetypal Ideas

Perhaps the most iconic and influential answer to the problem of universals comes from Plato, whose theory of Forms (often also referred to as Ideas) postulates their independent and transcendent existence. For Plato, the sensory world we perceive is a mere shadow, an imperfect reflection of a higher, unchanging reality. In this higher realm—the World of Forms—reside the perfect, eternal, and immutable archetypes of everything we experience.

- What are Platonic Forms?

- Perfect Models: They are the ideal blueprints or paradigms of which all particular things are imperfect copies. For instance, there is the perfect Form of Beauty, which particular beautiful objects merely participate in.

- Eternal and Unchanging: Unlike particulars, which are born, decay, and die, Forms exist outside of space and time, never altering.

- Non-Physical: They are apprehended not through the senses, but through intellect and reason.

- Objects of True Knowledge: While particulars offer only opinion, the Forms are the true objects of episteme (certain knowledge).

Plato's metaphysics posits that a particular red apple is red because it participates in, or imitates, the Form of Redness. A just act is just because it reflects the Idea of Justice. This theory provides a robust framework for understanding how we can have knowledge of universal truths despite the ever-changing nature of the empirical world. It suggests that our capacity to recognize "dog-ness" in different dogs stems from an innate recollection of the Form of Dog.

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Substance and Essence

Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, offered a powerful counter-argument to his mentor's transcendent Forms. While Aristotle agreed that universals exist and are crucial for knowledge, he firmly rejected the notion of a separate, non-physical realm. For Aristotle, the Form of a thing is not separate from it but is immanent within the particular itself.

Aristotle's metaphysics centers on the concept of substance, which is a composite of form and matter. The form is the essence, the "what it is" of a thing, while matter is the "out of which it is made."

- Form as Essence: The Form of a human being (rational animality) is not in some separate realm, but is the very essence of this individual human being, Socrates.

- Inseparable from Matter: For Aristotle, you cannot have a Form without matter, nor matter without some form. They are intrinsically linked in actual existing things.

- Known Through Abstraction: We come to know universals by abstracting them from our experience of many particulars. By observing many individual dogs, we discern the Form or essence of "dog-ness" that is present in each.

Aristotle's approach grounds universals in the empirical world, making them knowable through sensory experience and rational analysis of particulars. The Idea of "tree" is not a perfect tree existing elsewhere, but the common structure, function, and definition that resides within every individual tree. This moderate realism stands in stark contrast to Plato's extreme realism.

The Medieval Debate: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The problem of universals continued to be a central preoccupation throughout the medieval period, with Christian theologians and philosophers adapting and debating the legacies of Plato and Aristotle. The discussion fractured into several distinct positions, each with profound theological and epistemological implications.

| Position | Key Argument | Relationship to Universal and Particular

The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms is a critical inquiry into the very fabric of reality. It asks whether abstract concepts like "humanity" or "redness" exist independently of individual humans or red objects, or if they are merely mental constructs or convenient linguistic labels. This debate, profoundly shaped by philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, has defined the landscape of metaphysics for millennia, influencing our understanding of knowledge, truth, and the fundamental constituents of existence.

The Enduring Riddle: Universal and Particular

The world around us is an intricate tapestry of individual entities: this specific tree, that particular shade of blue, this unique act of courage. These are what philosophers term particulars. Yet, our minds effortlessly group them, recognizing underlying commonalities. We speak of "trees" in general, the concept of "blue," or the virtue of "courage." These overarching concepts, properties, or types are known as universals.

The central philosophical challenge lies in determining the metaphysical status of these universals. Do they possess an existence independent of the individual instances that exemplify them? Or are they merely convenient labels, mental abstractions, or properties inextricably bound to the physical world? This isn't just an academic quibble; the answer to this question profoundly influences our theories of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and even the nature of scientific classification. The search for the true nature of these overarching concepts has driven thinkers from the ancient Greek agora to the modern lecture hall.

Plato's Realm of Forms: The Archetypal Ideas

Perhaps the most iconic and influential answer to the problem of universals comes from Plato, whose theory of Forms (often also referred to as Ideas) postulates their independent and transcendent existence. For Plato, the sensory world we perceive—the realm of particulars—is a mere shadow, an imperfect reflection of a higher, unchanging reality. In this higher realm—the World of Forms—reside the perfect, eternal, and immutable archetypes of everything we experience.

Plato's metaphysics posits a radical dualism, suggesting that true reality is not found in the fleeting, perishable objects of our senses, but in these perfect, non-physical entities.

- Key Characteristics of Platonic Forms:

- Perfect Models: Forms are the ideal blueprints or paradigms of which all particular things are imperfect copies. For instance, there is the perfect Form of Beauty, which particular beautiful objects merely "participate in" or "imitate."

- Eternal and Unchanging: Unlike particulars, which are born, decay, and die, Forms exist outside of space and time, never altering. They are impervious to change.

- Non-Physical and Intelligible: They are apprehended not through the senses, but through pure intellect and reason. One cannot see the Form of Justice, but one can grasp its essence intellectually.

- Objects of True Knowledge: While particulars offer only opinion or belief, the Forms are the true objects of episteme (certain, infallible knowledge). Understanding the Forms is the path to wisdom.

For Plato, a particular red apple is red because it participates in, or imperfectly imitates, the Form of Redness. A just act is just because it reflects the Idea of Justice. This theory provides a robust framework for understanding how we can have knowledge of universal truths despite the ever-changing nature of the empirical world. It suggests that our capacity to recognize "dog-ness" in different dogs stems from an innate recollection of the Form of Dog, perhaps implanted in our souls before birth.

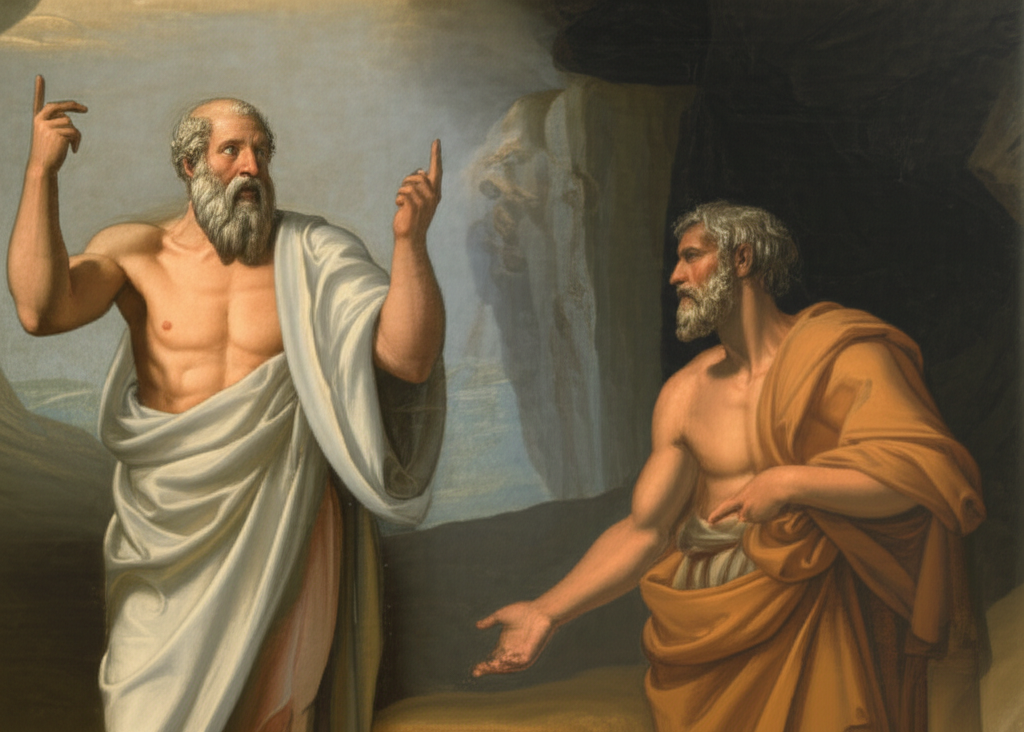

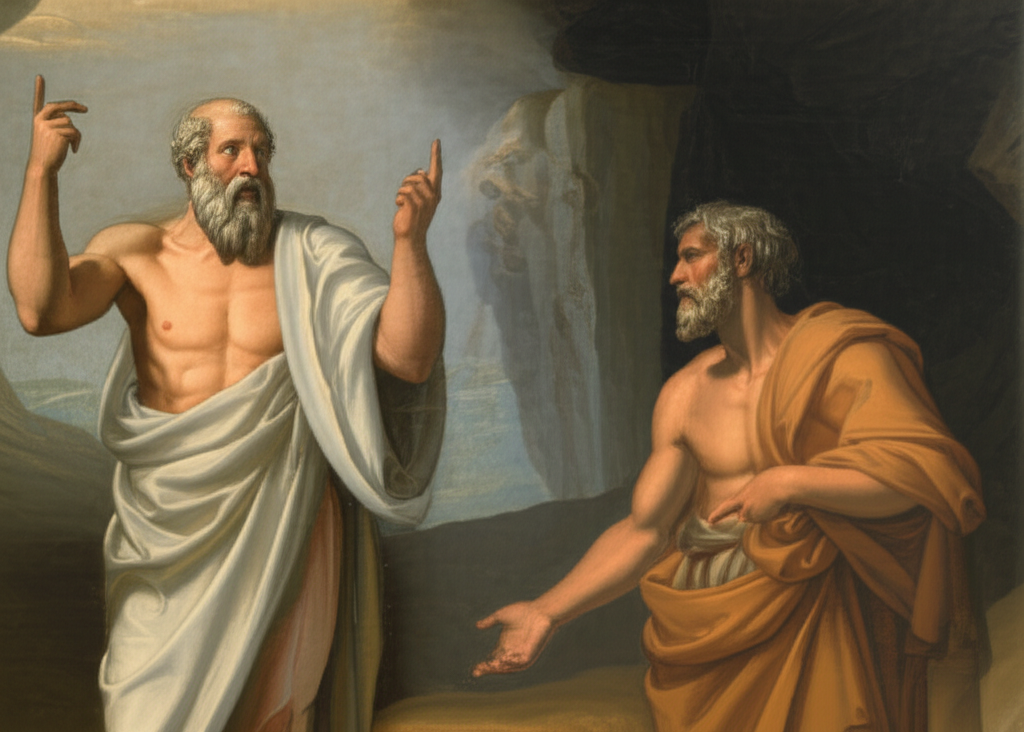

(Image: A classical Greek fresco depicting Plato pointing upwards towards the heavens, symbolizing his theory of transcendent Forms, while Aristotle gestures downwards towards the earth, representing his focus on immanent reality. Behind them, a subtle depiction of a cave opening, referencing Plato's Allegory of the Cave, with shadows on one wall and a faint light representing the true Forms. The scene is bathed in the warm, diffused light typical of ancient art, highlighting the intellectual intensity of the two figures.)

Aristotle's Immanent Forms: Substance and Essence

Plato's most famous student, Aristotle, offered a powerful counter-argument to his mentor's transcendent Forms. While Aristotle agreed that universals exist and are crucial for knowledge, he firmly rejected the notion of a separate, non-physical realm. For Aristotle, the Form of a thing is not separate from it but is immanent within the particular itself.

Aristotle's metaphysics centers on the concept of substance, which he understood as a composite of form and matter. The form is the essence, the "what it is" of a thing, while matter is the "out of which it is made." They are two inseparable aspects of any existing particular.

- Form as Essence: The Form of a human being (its rational animality) is not in some separate realm, but is the very essence of this individual human being, Socrates. It defines what Socrates is.

- Inseparable from Matter: For Aristotle, you cannot have a Form without matter, nor matter without some form. They are intrinsically linked in actual existing things. A bronze statue (matter) only becomes a statue (form) when the bronze is given a specific shape.

- Known Through Abstraction: We come to know universals by abstracting them from our experience of many particulars. By observing many individual dogs, we discern the Form or essence of "dog-ness" that is present in each. This process of abstraction allows the mind to grasp the universal in the particular.

Aristotle's approach grounds universals in the empirical world, making them knowable through sensory experience and rational analysis of particulars. The Idea of "tree" is not a perfect tree existing elsewhere, but the common structure, function, and definition that resides within every individual tree. This "moderate realism" stands in stark contrast to Plato's "extreme realism," bringing the universals down to earth, so to speak.

The Medieval Debate: Realism, Nominalism, and Conceptualism

The problem of universals continued to be a central preoccupation throughout the medieval period, with Christian theologians and philosophers adapting and debating the legacies of Plato and Aristotle. The discussion fractured into several distinct positions, each with profound theological, epistemological, and even linguistic implications for understanding the metaphysical status of universals.

This period saw the development of various "isms" to categorize different answers to the question: Do universals exist, and if so, where and how?

| Philosophical Position | Core Tenet Regarding Universals

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Metaphysical Status of Universal Forms philosophy"