The Enduring Riddle: Unpacking the Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many

The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many stands as one of philosophy's most profound and persistent inquiries, grappling with the fundamental nature of reality itself. At its core, it asks: How can the universe, which appears as a vast multitude of distinct, changing things, also possess an underlying unity or coherence? Is reality ultimately a single, unified Being, or is it composed of countless discrete elements? This article delves into the historical development of this crucial metaphysical question, exploring how thinkers from the ancient world to the modern era have grappled with the tension between unity and multiplicity, and the role of relation in bridging this divide.

Introduction: The Fundamental Paradox of Existence

As Daniel Sanderson, I've spent countless hours poring over the Great Books of the Western World, and few questions resonate with such persistent power as the problem of the One and Many. It's not merely an academic puzzle; it's the very bedrock upon which our understanding of existence rests. Metaphysics, the branch of philosophy concerned with the fundamental nature of reality, asks us to look beyond the superficial appearance of things and probe their ultimate essence. And when we do, we invariably confront a paradox: the world presents itself as an overwhelming Many – individual objects, events, people, ideas – yet our minds constantly seek to understand it as a coherent One, to find patterns, laws, and underlying principles that bind it all together.

This isn't just about counting. It's about Being itself. Is reality fundamentally singular, or plural? And if it's both, how do the 'One' and the 'Many' relate to each other? How can a single tree be composed of countless leaves, branches, and cells, yet still be one tree? How can society be a collection of individuals, yet also a singular entity with its own laws and identity? These questions force us to confront the very structure of reality and our perception of it.

Tracing the Roots: Ancient Greece and the Birth of the Problem

The problem of the One and Many is as old as philosophy itself, finding its earliest and most potent expressions among the Pre-Socratic philosophers.

Parmenides' Unchanging One: The Radical Monism of Being

One of the most radical answers came from Parmenides of Elea. For Parmenides, true Being is a single, indivisible, unchanging, eternal, and perfect One. Multiplicity, change, motion, and difference are mere illusions of the senses. To speak of "nothing" or "non-being" is illogical, for if something exists, it is. Therefore, there can be no empty space for things to move into, no division, no coming into being or passing away. Reality, in its essence, is a solid, spherical, undifferentiated One. This stark monism presented a profound challenge: how do we reconcile this unified Being with the chaotic Many we experience daily?

Heraclitus' Flux and the Many: Constant Change and Multiplicity

In stark contrast, Heraclitus of Ephesus emphasized the primacy of change and multiplicity. His famous dictum, "You cannot step into the same river twice," captures his belief that everything is in a constant state of flux. Being is not static, but dynamic, a perpetual becoming. While Heraclitus acknowledged an underlying logos or rational principle governing this change, his focus was firmly on the ever-shifting Many. The tension between Parmenides' static One and Heraclitus' dynamic Many laid the groundwork for centuries of philosophical debate.

Plato's Forms as a Solution: Bridging the Gap

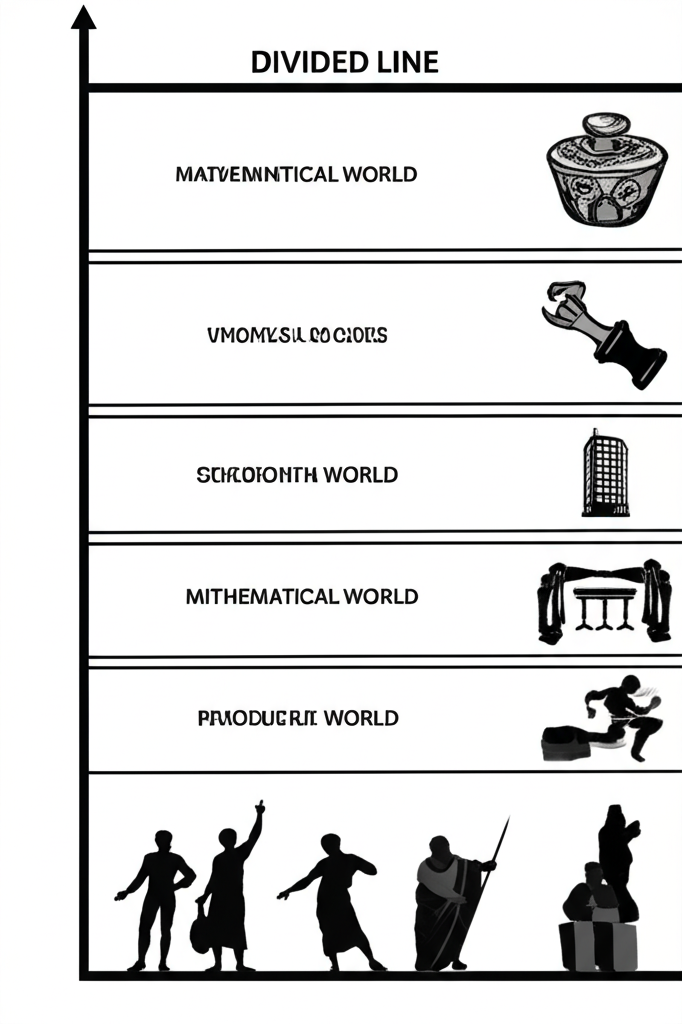

It was Plato, building upon the insights of his predecessors and the teachings of Socrates, who offered a monumental attempt to reconcile the One and the Many through his Theory of Forms. For Plato, the changing, imperfect world of our senses (the Many) is merely a pale reflection of a more fundamental, eternal, and perfect realm of Forms (the One).

on one side and the intelligible world (mathematical objects, Forms) on the other, connected by a central line representing the ascent of knowledge. The Forms are depicted as radiant, geometric ideals, while the physical objects are less defined and more numerous.)

on one side and the intelligible world (mathematical objects, Forms) on the other, connected by a central line representing the ascent of knowledge. The Forms are depicted as radiant, geometric ideals, while the physical objects are less defined and more numerous.)

Each particular, beautiful thing we encounter in the world participates in the Form of Beauty. Each just act reflects the Form of Justice. These Forms are the true Being – singular, unchanging, and perfect – providing the underlying unity and intelligibility for the diverse and transient Many we perceive. The relation between the particular and the universal, the concrete and the abstract, became a central theme.

Aristotle's Substance and Categories: Finding Unity in Individual Being

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a different approach. While acknowledging the importance of universal concepts, he argued that true Being resides primarily in individual, concrete substances. For Aristotle, a particular horse is more real than the universal "horseness." However, he didn't abandon the idea of unity. He proposed that each substance is a compound of form (its essence, what makes it what it is) and matter (the stuff it's made of). The form provides the unity and intelligibility to the matter, allowing us to categorize and understand the diverse Many.

Aristotle's categories (substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, position, state, action, affection) provided a framework for understanding how different aspects of Being are organized and connected. The concept of relation became crucial for understanding how individual substances interact and form larger wholes.

Table: Comparing Ancient Approaches to the One and Many

| Philosopher | Primary Emphasis | View of "The One" | View of "The Many" | Key Concept for Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parmenides | Absolute Unity | Static, indivisible Being | Illusionary | Non-existent (no division) |

| Heraclitus | Constant Flux | Underlying Logos (principle of change) | Ever-changing particulars | Dynamic tension, conflict |

| Plato | Ideal Forms | Eternal, perfect Forms | Imperfect, changing particulars | Participation, Imitation |

| Aristotle | Individual Substance | Form within substance | Concrete, individual substances | Categories, Predication |

The Medieval Echo: Universals and Particulars

The problem of the One and Many resurfaced with vigor during the Medieval period, particularly in the "Problem of Universals." This debate directly addressed how universal concepts (like "humanity" or "redness") – which seem to represent a 'One' – relate to the individual, particular things (specific humans, specific red objects) – the 'Many' – that embody them.

- Realism: Argued that universals exist independently of our minds, often seen as Platonic Forms or as inherent properties within things (like Aristotle).

- Nominalism: Contended that universals are merely names or labels we apply to collections of similar particulars; only individuals truly exist.

- Conceptualism: Proposed that universals exist as concepts in the mind, formed by abstracting common features from particulars.

This debate, central to Scholastic philosophy, continued to explore the fundamental relation between general categories and specific instances, influencing theological arguments about the nature of God and the human soul.

Modern Perspectives: From Substance to Structure

The Enlightenment and subsequent philosophical movements re-imagined the problem.

Baruch Spinoza offered a radical monism, positing a single, infinite substance – God or Nature – of which everything else is merely a mode or attribute. This grand One encompasses all Being, and the Many are simply expressions of its infinite nature, unified by an underlying rational order.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in contrast, proposed a universe composed of an infinite number of simple, indivisible substances called monads. Each monad is a self-contained "mirror of the universe," reflecting the totality from its unique perspective. The challenge for Leibniz was to explain how these independent monads could appear to interact or form a coherent whole without direct causal relation. His solution was a "pre-established harmony" orchestrated by God.

Later, Immanuel Kant shifted the focus from the ultimate nature of reality itself (the noumenal realm, which he deemed unknowable) to the structure of human experience. He argued that the unity we perceive in the world is not inherent in the things-in-themselves but is imposed by the categories of our understanding. Our mind actively synthesizes the disparate sensory data (the Many) into a coherent, unified experience (the One) through concepts like causality and substance.

Key Philosophical Concepts in Play

To truly grasp the One and Many, we must understand the core concepts it engages:

- Being: This is the most fundamental concept, referring to existence itself. What does it mean for something to be? Is Being singular and undifferentiated, or plural and diverse?

- Relation: How do different things connect? Is relation a fundamental aspect of reality, or merely a way our minds organize independent entities? Can the Many form a One without some form of relation?

- Unity and Multiplicity: These are the two poles of the problem. Unity refers to wholeness, coherence, and singularity. Multiplicity refers to diversity, difference, and plurality.

- Identity and Difference: How do we distinguish one thing from another (difference) while recognizing what makes it uniquely itself (identity)? This plays into how individual members of the Many maintain their distinctness while potentially belonging to a larger One.

Why This Ancient Problem Still Haunts Us

The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many is far from an outdated curiosity. It continues to inform and challenge contemporary thought across various disciplines:

- In Science: Physicists search for a unified "Theory of Everything" (the One) that can explain the fundamental forces and particles (the Many) of the universe. Biologists grapple with how individual cells (the Many) form a single, coherent organism (the One).

- In Philosophy of Mind: How can the myriad neural firings and processes in the brain (the Many) give rise to a single, unified consciousness (the One)? This is the hard problem of consciousness, deeply rooted in the One and Many.

- In Ethics and Politics: How do individual rights and freedoms (the Many) reconcile with the common good and the collective identity of a society or state (the One)? Debates over individualism versus collectivism are modern manifestations of this ancient tension.

- In Ontology: Contemporary ontologists continue to explore questions of mereology (the study of parts and wholes), composition, and the nature of properties and universals, all of which are direct descendants of the One and Many problem.

Conclusion: A Continual Inquiry into Existence

The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many is not a puzzle with a single, definitive answer. Instead, it represents a fundamental tension inherent in our experience of reality and our attempts to comprehend it. From Parmenides' unwavering monism to Plato's transcendent Forms, Aristotle's immanent substances, and the intricate systems of modern philosophy, thinkers have tirelessly sought to understand how the seemingly disparate elements of existence cohere into a meaningful whole.

It compels us to continually question the nature of Being, the role of relation in structuring our world, and the very limits of our understanding. As we navigate a world of ever-increasing complexity, this ancient metaphysical inquiry remains as vital as ever, inviting us to ponder the deepest mysteries of unity and diversity that define our existence.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Parmenides One vs Heraclitus Many philosophy""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato Theory of Forms Explained" or "Aristotle Metaphysics Substance""