The Enduring Riddle: Navigating the Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many

The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many stands as one of philosophy's most fundamental and enduring challenges. At its core, it questions how the apparent multiplicity of the world – the diverse objects, experiences, and individuals we encounter – can be reconciled with a presumed underlying unity or a singular Being. Is reality ultimately one unified whole, or is it a collection of distinct, irreducible parts? This article delves into the historical origins, philosophical implications, and various attempts to resolve this profound inquiry, exploring how thinkers from antiquity to the present have grappled with the fundamental relation between unity and diversity in the fabric of existence.

Unpacking the Paradox: A Summary

The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many is the philosophical quandary concerning how the universe, or reality itself, can be both unified and diverse simultaneously. It asks whether the ultimate nature of Being is singular and indivisible (the "One") or composed of multiple, distinct entities (the "Many"), and how these two seemingly contradictory aspects can coexist or be reconciled. This problem touches upon concepts of identity, change, substance, and the very structure of reality, forcing us to confront the nature of relation between parts and wholes.

The Ancient Echoes: Where the Problem Began

Our journey into the Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many inevitably leads us back to the pre-Socratic philosophers, whose audacious inquiries set the stage for Western thought. These thinkers, as preserved in the fragments and interpretations found in the Great Books of the Western World, were the first to systematically question the underlying nature of reality beyond mythological explanations.

Parmenides and the Unchanging One

Perhaps the most radical early proponent of the "One" was Parmenides of Elea. His philosophy, articulated in his poem On Nature, posits that Being is absolutely singular, eternal, unchanging, and indivisible. For Parmenides, any talk of multiplicity, change, or non-being is a mere illusion of the senses, a path of "opinion" rather than truth.

- Parmenides' Core Argument:

- What is, is. What is not, cannot be conceived or spoken of.

- Therefore, Being is all there is.

- If Being is all there is, there can be no empty space (non-being) for things to move into, hence no change.

- If there is no change, there can be no multiplicity, as multiplicity implies distinct parts that can change relation to each other.

- Conclusion: Reality is a single, undifferentiated, eternal One.

Parmenides' stark monism presented an enormous challenge: how could the world of our experience, filled with countless changing things, be reconciled with this unchanging One?

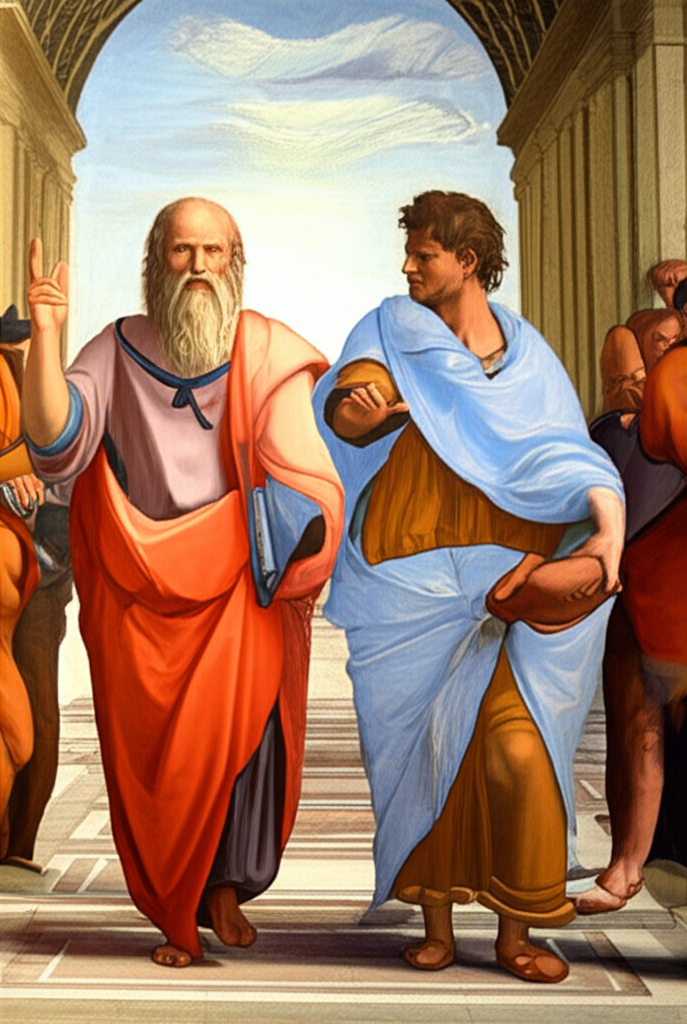

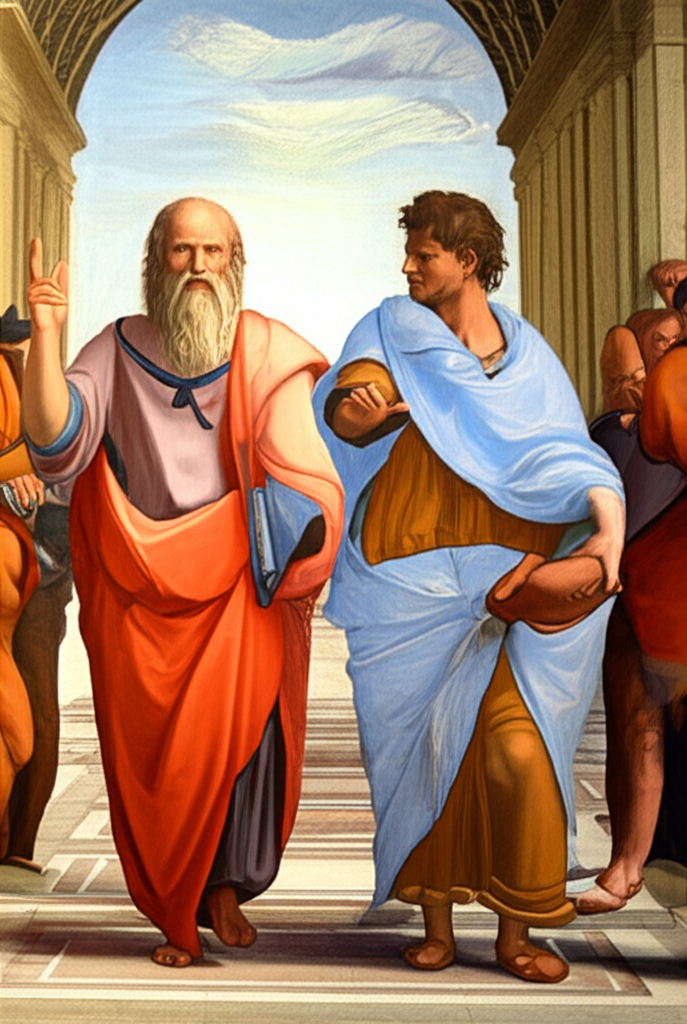

Plato's Forms and the Bridge to Multiplicity

Plato, deeply influenced by Parmenides' insistence on an unchanging reality, sought to resolve the problem not by denying multiplicity outright, but by re-situating true Being. In his theory of Forms (or Ideas), Plato posits a realm of perfect, eternal, and unchanging archetypes (the "One" in a different sense for each universal concept) that exist independently of the sensible world. The many particular objects we perceive are merely imperfect copies or participants in these Forms.

- Plato's Dualism:

- Realm of Forms (The One): Intelligible, eternal, perfect, unchanging universals (e.g., the Form of Beauty, the Form of Justice, the Form of Man). These are the true Being.

- Realm of Particulars (The Many): Sensible, temporal, imperfect, changing instances of the Forms. These "participate" in the Forms.

Plato's solution introduces a sophisticated relation between the ideal "One" and the observable "Many," but it also raises new questions about how these two distinct realms interact and how particulars relate to their ideal archetypes.

Aristotle's Substance and Immanent Unity

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a different approach, rejecting the separate realm of Forms. For Aristotle, the true Being resides in individual, concrete substances – the particular "thises" we encounter. Each substance is a composite of form (its essence, what it is) and matter (what it is made of).

- Aristotle's Immanent View:

- The "One" is found in the form within each individual substance, defining its nature.

- The "Many" are the countless individual substances themselves, each with its own unique matter-form composite.

- Universals (the "One" of a species, e.g., "Man") exist only in the particulars; they are not separate entities.

- The relation between form and matter is one of inherence, not participation in a separate realm.

Aristotle's philosophy brought the discussion of Being back to the empirical world, attempting to find unity within multiplicity rather than beyond it.

Defining the Terms: One, Many, Being, and Relation

To fully grasp the Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many, it's crucial to clarify the philosophical weight carried by these seemingly simple terms:

| Term | Philosophical Meaning

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Metaphysical Problem of the One and Many philosophy"