The Unseen Foundation: Grappling with the Metaphysical Concept of Being

The Metaphysical Concept of Being plunges us into the deepest waters of philosophy: what does it truly mean to exist? This article explores how metaphysics, the branch of philosophy dedicated to uncovering the fundamental nature of reality, grapples with "Being" – not merely a particular being, but the very essence of Being itself. From the ancient pre-Socratics wrestling with the One and Many to the intricate systems of Plato and Aristotle, we uncover the enduring human quest to understand the ultimate Principle underlying all existence, challenging us to look beyond mere appearances to the very ground of what is.

What is "Being," Anyway?

It sounds simple, doesn't it? "Being." Yet, few concepts have proven as stubbornly elusive, as profoundly divisive, or as utterly central to human thought as this seemingly straightforward notion. When philosophers speak of "Being," they are not just referring to the fact that something exists, like a tree or a star. Instead, they are probing the conditions of existence, the nature of reality, and the fundamental categories through which we apprehend everything that is. It's the ultimate question: What is it to be? And why is there something rather than nothing?

Metaphysics, as a discipline, seeks to answer these questions by investigating the first principles of reality, going beyond the empirical sciences to explore concepts like existence, causality, time, and space. At its core, the study of Being is the search for the underlying structure and meaning of everything.

The Ancient Genesis: From Cosmos to Concept

The philosophical inquiry into Being began in earnest with the pre-Socratic thinkers of ancient Greece, as documented in the Great Books of the Western World. They were the first to systematically move beyond mythological explanations to seek rational accounts of the cosmos.

- Parmenides of Elea famously asserted that "What is, is; what is not, is not." For Parmenides, Being is eternal, unchanging, indivisible, and perfect. Any perceived change or multiplicity in the world is an illusion of the senses. Reality, for Parmenides, is a singular, undifferentiated whole – the ultimate One.

- Heraclitus of Ephesus, in stark contrast, declared that "You cannot step into the same river twice." He believed that everything is in a constant state of flux, change, and becoming. Fire, for him, was the fundamental element, symbolizing this ceaseless transformation. Reality is not static Being, but dynamic Becoming.

This fundamental disagreement gave rise to the enduring philosophical problem of the One and Many: How can we reconcile the apparent multiplicity, change, and diversity of the world (the Many) with a search for a unified, stable, and ultimate reality (the One)? This question became a central challenge for subsequent philosophers.

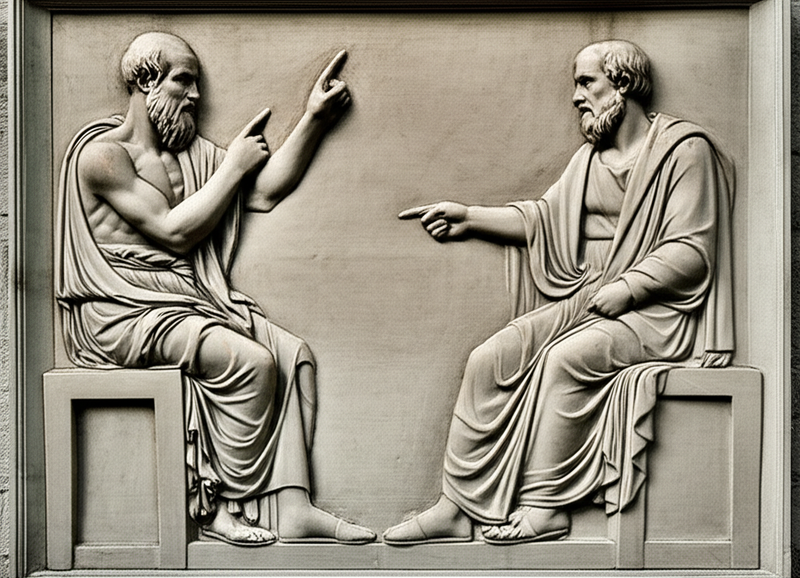

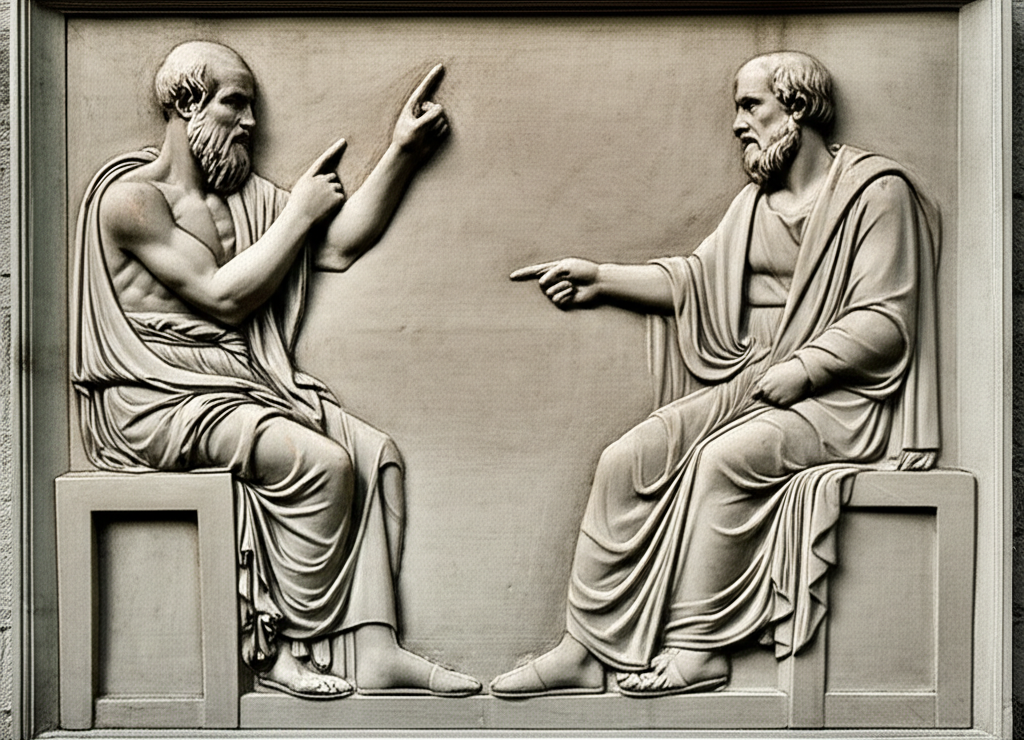

Plato's Forms and Aristotle's Substances

The intellectual giants, Plato and Aristotle, each offered sophisticated frameworks to address the nature of Being, drawing heavily on the pre-Socratic insights while forging new paths.

-

Plato's Theory of Forms: For Plato, true Being resides not in the fleeting, imperfect world we perceive through our senses, but in an eternal, immutable realm of Forms (or Ideas). These Forms – such as the Form of Beauty, Justice, or Goodness – are perfect, non-physical blueprints that particular things in the physical world participate in. A beautiful painting is beautiful because it participates in the Form of Beauty. The Forms represent the ultimate reality, the true objects of knowledge, and the highest expression of Being.

-

Aristotle's Metaphysics of Substance: Aristotle, Plato's student, brought the concept of Being back down to earth, focusing on individual, concrete things. For Aristotle, the primary sense of Being is substance (ousia). A substance is an individual entity (like a particular human, a horse, or a tree) that exists independently and underlies all its properties. He distinguished between:

- Essence: What a thing is fundamentally (e.g., rationality for a human).

- Accidents: Properties that can change without the thing ceasing to be what it is (e.g., a human's height or hair color).

Aristotle also introduced the crucial concepts of potentiality and actuality to explain change and development. A seed has the potential to be a tree; the fully grown tree is the actuality of that potential. Thus, Being encompasses both what a thing is now and what it can become.

| Philosopher | Primary Locus of Being | Key Concept(s) | Relation to Particulars | Ultimate Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Eternal Forms | Participation | Particulars participate in Forms | The Form of the Good |

| Aristotle | Individual Substances | Essence, Potentiality, Actuality | Particulars are substances with essences | The Unmoved Mover |

Unpacking the Principles of Existence

To speak of Being is often to seek its Principle – the fundamental ground from which all else springs, the ultimate "why" behind existence. For Plato, the ultimate Principle was the Form of the Good, illuminating all other Forms and giving them their intelligibility and reality. For Aristotle, the ultimate Principle was the Unmoved Mover, a pure actuality that causes all motion in the cosmos without itself being moved, serving as the ultimate cause and end of all things.

The concept of Being, therefore, isn't monolithic. It manifests in various ways:

- Existence: The simple fact of being there.

- Essence: The whatness of a thing, its defining characteristics.

- Substance: The underlying reality that persists through change.

- Actuality: The state of being fully realized.

- Potentiality: The capacity to become something else.

These different dimensions highlight the complexity of asking "what is Being?" It forces us to consider not just that something is, but what it is, how it is, and why it is.

The Enduring Mystery and Modern Echoes

The metaphysical concept of Being is not a relic of ancient thought; it continues to challenge and inspire philosophers today. From Descartes' foundational "I think, therefore I am" (cogito, ergo sum) – establishing the Being of the thinking self – to Heidegger's profound exploration of Dasein (human Being-in-the-world), the question remains central. How do we, as finite beings, comprehend infinite Being? How do we integrate the diverse experiences of life with a search for unified meaning or truth, thereby tackling the One and Many in our own existence?

Ultimately, to ponder the Metaphysical Concept of Being is to engage in the most profound act of self-reflection, seeking to understand not just what is, but what it means to be – a quest that remains as vital today as it was in the ancient academies.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Parmenides vs Heraclitus One and Many""

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of Forms explained""