The Metaphysical Concept of Being: Unpacking Existence

The concept of Being stands as the foundational cornerstone of Metaphysics, the branch of philosophy dedicated to understanding the fundamental nature of reality. It is an inquiry into what it means for something "to be," exploring not just existence itself, but also the various modes, categories, and ultimate Principles that constitute reality. From ancient Greek contemplation of the One and Many to scholastic distinctions of essence and existence, the philosophical journey through Being seeks to grasp the very fabric of everything that is, was, or could be. This article delves into this profound concept, tracing its historical development and enduring significance.

What is Being? A Philosophical Inquiry

At its heart, Being is perhaps the most fundamental and elusive concept in philosophy. It refers to the state of existing, the fact of being real. Yet, simply defining it as "existence" barely scratches the surface of its metaphysical depth. Philosophers have grappled with questions such as: What does it mean for something to exist? Are there different kinds of Being? Is there an ultimate Being from which all else derives?

Early Greek thinkers, particularly Parmenides of Elea, famously asserted that "what is, is, and what is not, is not." For Parmenides, Being was eternal, unchanging, indivisible, and perfect – a singular, undifferentiated reality. His stark monism challenged the very notion of change and plurality, setting the stage for centuries of debate. In contrast, Heraclitus emphasized constant flux and change, famously stating that "you cannot step into the same river twice," suggesting that Being is fundamentally dynamic.

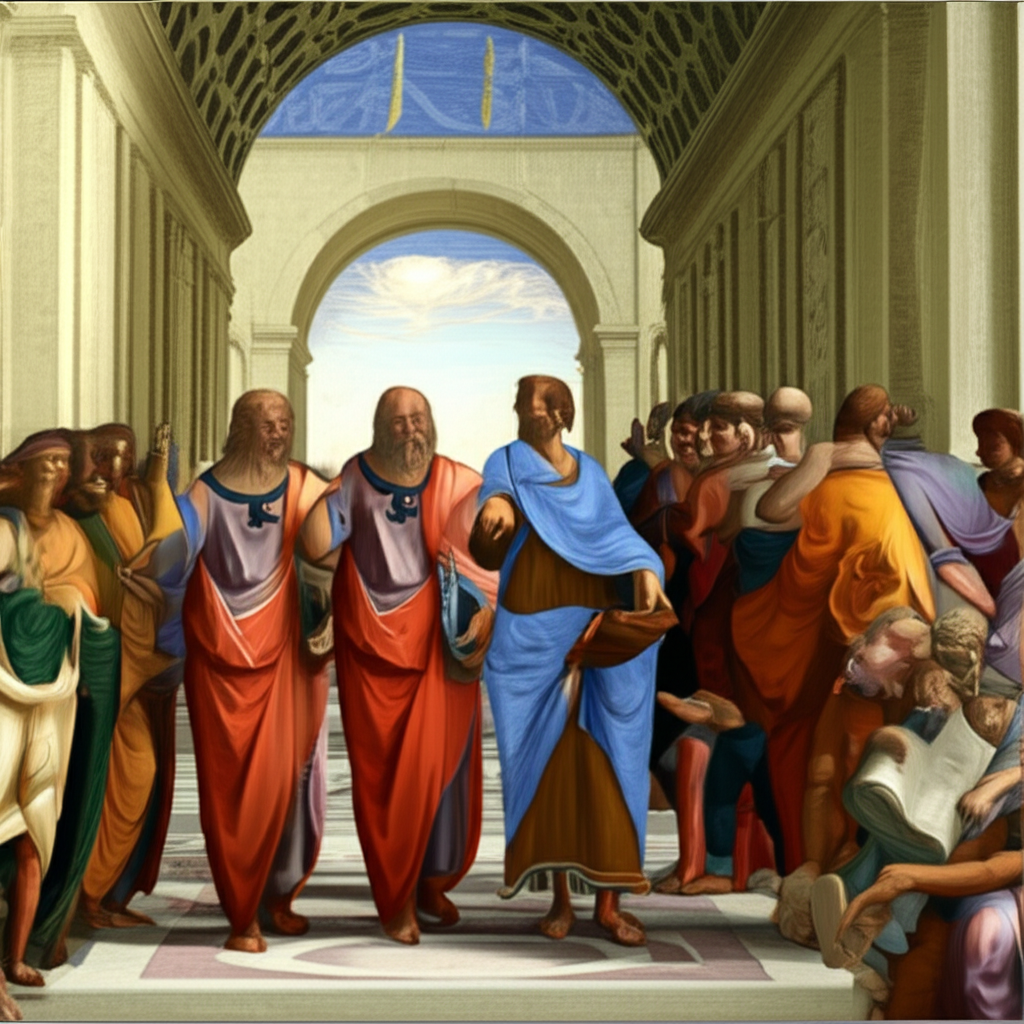

The towering figures of Plato and Aristotle, whose works form a substantial part of the Great Books of the Western World, offered more nuanced accounts. Plato posited a realm of eternal, unchanging Forms (e.g., the Form of Beauty, the Form of Justice) as the true Being, with the sensible world being merely an imperfect reflection. For Plato, the truest Being resided in these perfect, intelligible universals.

Aristotle, while rejecting Plato's separate realm of Forms, developed a sophisticated system of categories to describe the various ways in which things are. He distinguished between substance (the primary Being – what a thing is in itself) and accidents (qualities, quantities, relations, etc., that modify a substance). For Aristotle, Being is not a single genus but rather something said "in many ways," all ultimately referring back to substance. He also introduced the crucial distinction between actuality and potency, explaining change not as a transition from non-being to being, but from potential being to actual being.

The Problem of the One and Many

One of the persistent challenges in understanding Being is the "Problem of the One and Many." How can the seemingly countless individual entities, properties, and experiences in the world be understood in relation to a unifying concept of Being? If Being is truly singular and undifferentiated (as Parmenides suggested), how do we account for the diversity we perceive? Conversely, if reality is merely a collection of distinct particulars, what makes them all "beings" in a common sense?

Plato's theory of Forms was an attempt to resolve this: the Many (individual beautiful things) participate in the One (the Form of Beauty). Aristotle's concept of substance and his categories provided another framework, suggesting that while specific substances are many, they all are in a primary sense, with other modes of Being depending on them.

Medieval philosophers, particularly Thomas Aquinas, building on Aristotle, explored the relationship between essence (what a thing is) and existence (the act of Being). For Aquinas, only God's essence is His existence; for all created things, their essence is distinct from their existence, meaning they receive their Being from a higher Principle. This distinction became central to understanding the contingency of creation and the necessity of a divine ground of Being.

Being as First Principle

Many metaphysical systems posit Being as the ultimate Principle or ground of all reality. This often leads to discussions of a "First Being" or "Absolute Being," which is uncaused, self-sufficient, and the source of all other Being.

- Cosmological Arguments: These arguments for the existence of God often rely on the idea that everything that begins to exist has a cause, and this chain of causes must ultimately lead to an uncaused first cause, a necessary Being.

- Ontological Arguments: These arguments attempt to prove God's existence from the very concept of Being itself, often defining God as "that than which no greater can be conceived," implying that such a Being must exist in reality, not just in the mind.

For thinkers like Aquinas, God is ipsum esse subsistens – "subsistent Being itself," the pure act of Being, without any potentiality or limitation. This ultimate Principle serves as the explanation for the Being of everything else.

Key Facets and Thinkers on Being

The exploration of Being has yielded numerous distinctions and perspectives throughout philosophical history:

| Philosophical Concept | Description | Key Thinkers (Great Books) |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Being | Undifferentiated, indeterminate existence, often conceived as the ultimate ground or source. | Parmenides, Plotinus |

| Being and Becoming | The distinction between static, unchanging reality and dynamic, ever-changing phenomena. | Parmenides (Being), Heraclitus (Becoming), Plato (Forms as Being, sensory world as Becoming) |

| Substance & Accident | Aristotle's primary distinction: Substance is what a thing is in itself; accidents are properties that adhere to a substance. | Aristotle |

| Actuality & Potency | Aristotle's explanation of change: A thing's potentiality for Being (potency) becomes actualized (actuality). | Aristotle |

| Essence & Existence | Essence is "whatness" (the nature of a thing); Existence is "thatness" (the fact that it is). For created beings, these are distinct; for God, they are identical. | Thomas Aquinas, Avicenna (via medieval philosophy) |

| Cogito Ergo Sum | Descartes' famous declaration: "I think, therefore I am," establishing the Being of the thinking subject as indubitable. | René Descartes |

| Noumenal & Phenomenal | Kant's distinction between things-in-themselves (noumena), which are unknowable, and things as they appear to us (phenomena), which constitute our experience of Being. | Immanuel Kant |

The Enduring Relevance of Being

The metaphysical concept of Being is far from an archaic philosophical curiosity. It underpins virtually every other philosophical inquiry. Our understanding of Being shapes our epistemology (how we know what is real), our ethics (what kinds of Being are valuable or good), and even our aesthetics (what constitutes the Being of beauty).

In contemporary thought, questions about Being persist in discussions of consciousness, artificial intelligence, the nature of reality in quantum physics, and even existentialist philosophy, which focuses on the Being of human existence and its unique challenges. The journey through the Great Books of the Western World reveals a continuous, evolving engagement with this most fundamental of questions, demonstrating its timeless importance.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Parmenides vs Heraclitus The One and Many""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Metaphysics Actuality and Potency""