The Mechanics of the Soul: An Inquiry into Its Operation and Essence

The concept of the soul has haunted humanity's philosophical inquiries for millennia, a profound mystery at the core of our understanding of self and existence. But what if we dared to ask not just what the soul is, but how it works? Can this elusive essence, often considered immaterial and divine, be understood through the lens of mechanics—a system of operations, cause-and-effect, and even physics? This pillar page delves into the historical and philosophical attempts to decipher the operational principles of the soul, exploring its relationship with the mind and body, and the implications of seeking its mechanics in a world increasingly defined by scientific understanding. From ancient Greek metaphysics to modern neurophilosophy, we embark on a journey to explore whether the soul is an ethereal spark, a complex mind algorithm, or something entirely beyond our mechanistic grasp.

Unpacking the "Soul" and "Mechanics" in Philosophical Discourse

Before we can investigate the mechanics of the soul, we must first define our terms—a task that, in philosophy, is rarely simple.

What is the Soul? A Multitude of Meanings

Historically, the soul has been conceived in myriad ways:

- The Principle of Life: In its most basic sense, the soul (psyche in Greek) was considered that which animates a living body, distinguishing it from inert matter. Aristotle, in De Anima, famously defined the soul as the form of a natural body having life potentially within it.

- The Seat of Consciousness and Identity: For many, the soul is synonymous with our individual mind, our unique personality, memories, and self-awareness. It is the "I" that persists through time.

- An Immortal Essence: Across various religious and philosophical traditions, the soul is often posited as an eternal, incorruptible part of a human being, destined to survive the death of the body. Plato, in Phaedo, presents compelling arguments for the soul's immortality.

- The Source of Moral Agency: The soul is frequently linked to our capacity for reason, ethics, and free will—the internal compass guiding our actions.

What are Mechanics? A Philosophical Interpretation

When we speak of mechanics in this context, we are not necessarily referring to gears and levers, but rather:

- Systematic Operation: The underlying principles, processes, and interactions that govern how something functions.

- Cause and Effect: The predictable relationships between inputs and outputs, actions and reactions.

- Underlying Structure: The components and their arrangement that enable a system to perform its function.

- Physical Laws: In a broader sense, whether the soul adheres to or operates within the bounds of natural, physical laws.

The core tension arises from this juxtaposition: Can something as seemingly immaterial and transcendent as the soul truly possess mechanics in any intelligible sense? Or does seeking its mechanics inherently reduce it to something less profound, less unique?

Ancient Echoes: The Soul in Classical Thought

The quest to understand the mechanics of the soul began with the earliest philosophers, who grappled with its nature long before the advent of modern science.

Plato's Tripartite Soul: An Internal Mechanism

Plato, a towering figure from the Great Books of the Western World, offered one of the most influential models of the soul's internal mechanics. In the Republic, he described the soul as having three distinct, yet interacting, parts:

| Part of the Soul | Function / Role | Analogy (from Plato's Phaedrus) |

|---|---|---|

| Reason (Logistikon) | Seeks truth, wisdom, and governs the soul. | The Charioteer, guiding the two horses. |

| Spirit (Thymoeides) | Seeks honor, courage, and righteous indignation. | The Noble Horse, striving for glory. |

| Appetite (Epithymetikon) | Seeks bodily desires, pleasure, and material comforts. | The Wild Horse, pulled by base desires. |

Plato envisioned a well-ordered soul where Reason, like a skilled charioteer, controls and harmonizes the Spirit and Appetite. This isn't mechanics in a modern physical sense, but it describes an intricate internal mechanism of psychological forces, where the proper functioning of the individual depends on the correct mechanics of these internal parts. The imbalance or struggle between these components was, for Plato, the root of moral and psychological dysfunction.

Aristotle's De Anima: The Soul as the Body's Form

Aristotle, Plato's student, took a different approach in De Anima (On the Soul). He rejected the idea of the soul as a separate entity that merely inhabits the body. Instead, he proposed that the soul is the form of the body—its organizing principle, its actuality.

- The Soul as Function: For Aristotle, the soul is not a "thing" but the mechanics by which a living body lives, perceives, and thinks. Just as the shape of an axe is its form, and its function (cutting) is its actuality, the soul is the form that makes a body a living, functioning organism.

- Hierarchy of Souls: Aristotle identified a hierarchy of soul types, each with its own mechanics:

- Nutritive Soul: Found in plants, responsible for growth, reproduction, and metabolism.

- Sensitive Soul: Found in animals, encompassing the nutritive functions plus sensation, desire, and locomotion.

- Rational Soul: Unique to humans, including all lower functions plus reason, thought, and intellect.

For Aristotle, understanding the mechanics of the soul meant understanding the biological and psychological functions of living beings. It was an immanent, rather than transcendent, inquiry.

The Dualist Dilemma: Descartes and the Mind-Body Problem

The modern era ushered in a new, profound challenge to understanding the mechanics of the soul through the work of René Descartes, another cornerstone of the Great Books of the Western World.

Descartes' Radical Dualism

Descartes, in his Meditations on First Philosophy and Passions of the Soul, famously established a radical dualism between two fundamentally different substances:

- Res Cogitans (Thinking Substance): The mind or soul, characterized by thought, consciousness, and non-extension in space.

- Res Extensa (Extended Substance): The body, characterized by extension, motion, and subject to the laws of physics.

Descartes saw the body as a complex machine, a system of mechanics operating according to physical laws. But where did the mind or soul fit in? He argued for their distinctness, yet acknowledged their interaction.

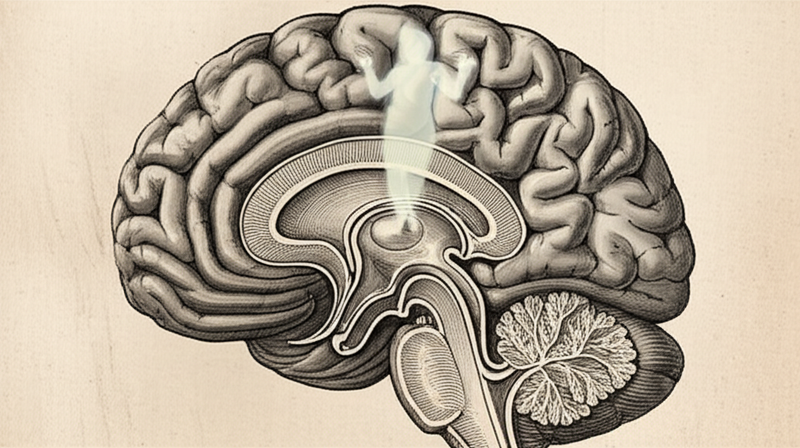

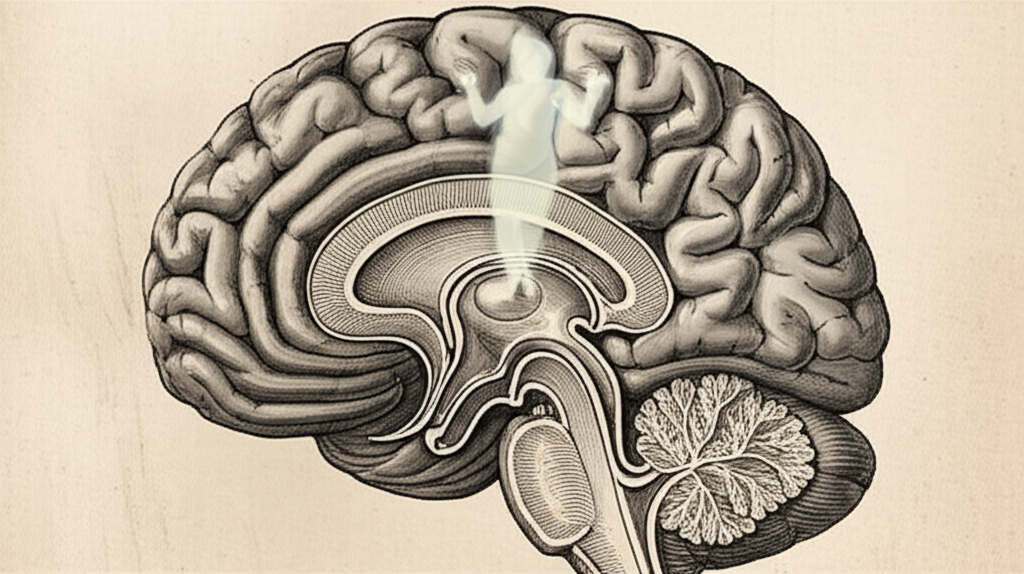

The Pineal Gland: A Mechanistic Bridge?

To explain the mechanics of interaction between the immaterial mind and the material body, Descartes famously (and controversially) proposed the pineal gland in the brain as the primary seat of the soul. He believed this small gland was where the "animal spirits" (a kind of subtle fluid) communicated between the soul and the body, allowing the mind to influence bodily movements and receive sensory information.

Descartes' solution, while attempting a mechanistic explanation for interaction, ultimately highlighted the immense difficulty of reconciling an immaterial soul with the physical world. This "mind-body problem" continues to be a central debate in philosophy.

Monism and Beyond: Alternative Frameworks

Not all philosophers accepted Descartes' dualism. Others proposed alternative mechanics for the soul's relationship with reality.

Spinoza's Attribute Monism: Parallel Mechanics

Baruch Spinoza, in his Ethics, offered a radical monistic view. He argued that there is only one substance: God, or Nature. Mind and body are not separate substances but two different attributes or expressions of this single substance.

- No Causal Interaction: For Spinoza, there is no mechanistic interaction between mind and body because they are not separate entities. Instead, mental events and physical events run in perfect parallel, like two sides of the same coin. What appears as a physical cause-and-effect in the body has a corresponding, parallel cause-and-effect in the mind.

- Determinism: Spinoza's system implies a profound determinism. The mechanics of the universe, including the mind and soul, are governed by necessary laws, leaving no room for free will in the traditional sense.

Leibniz's Pre-established Harmony: Spiritual Automata

Gottfried Leibniz proposed a universe composed of infinite, simple, indivisible substances called monads. Each monad is a self-contained universe, reflecting the entire cosmos from its own unique perspective.

- Spiritual Automata: Souls are a type of monad—spiritual automata that develop according to their own internal mechanics and programming.

- No Interaction, Only Harmony: Crucially, monads do not causally interact with each other. The apparent interaction between mind and body, or between any two things, is due to a "pre-established harmony" orchestrated by God at creation. All monads are perfectly synchronized, like countless clocks set to the exact same time, giving the illusion of interaction without any actual mechanics of influence.

Leibniz's theory offers a highly mechanistic universe, albeit one built on spiritual rather than physical components, with a divine mechanic setting all parts in motion from the outset.

The Soul, the Mind, and Modern Physics

As scientific understanding, particularly in physics and neuroscience, has advanced, the discussion of the soul's mechanics has shifted dramatically.

The Rise of Materialism and Emergence

With the success of physics in explaining the material world, many contemporary philosophers and scientists lean towards materialism. This view suggests that all phenomena, including the mind and what was once called the soul, can ultimately be reduced to or explained by physical processes.

- The Brain as the Mind's Mechanism: Neuroscience increasingly maps mental functions to specific brain regions and neural networks. Consciousness, thought, and emotion are seen as emergent properties—complex mechanics arising from the intricate interactions of billions of neurons.

- The Soul as an Illusion? From a strict materialist perspective, the soul as a separate, non-physical entity is often dismissed as a pre-scientific concept, an illusion created by the brain's complex mechanics.

Quantum Mechanics and Consciousness: A Speculative Bridge?

Some theories, often highly speculative, attempt to bridge the gap between physics and consciousness using principles from quantum mechanics.

- Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR): Proposed by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff, this theory suggests that consciousness arises from quantum processes within microtubules inside brain neurons. These quantum mechanics are proposed to be the basis for subjective experience.

- The "Hard Problem" of Consciousness: Even with advanced neuroscience, explaining how physical processes give rise to subjective experience (qualia) remains a profound challenge, often called the "hard problem" by David Chalmers. This suggests that the mechanics of the soul or mind might involve principles not yet fully understood by current physics.

While intriguing, these quantum theories are highly controversial within both physics and neuroscience, underscoring the ongoing difficulty in finding a physical mechanics for something as elusive as the soul or consciousness.

The Enduring Questions of the Soul's Mechanics

Even if we could fully map the mechanics of the soul or mind, profound philosophical questions would remain:

- Determinism vs. Free Will: If the soul operates according to predictable mechanics (whether physical or spiritual), does this negate free will? Are our choices merely the inevitable outputs of a complex system?

- The Source of Value and Meaning: If the soul is merely a mechanistic process, does it diminish human dignity, purpose, or the unique value of individual experience?

- The Nature of Personal Identity: What mechanics ensure that "I" remain "I" over time, despite constant change in my physical body and mental states? Is identity merely a narrative constructed by the mind?

These questions highlight that while understanding the mechanics of the soul might illuminate how it functions, it may not fully answer why it exists, or what its ultimate significance is.

Conclusion: The Soul, Mechanics, and the Unfolding Mystery

The journey to understand the mechanics of the soul is a testament to humanity's enduring curiosity and intellectual ambition. From Plato's internal psychological mechanisms to Aristotle's biological functions, Descartes' pineal gland hypothesis, and the modern pursuit of neural correlates of consciousness, each era has sought to impose a rational, often mechanistic, framework onto this most profound mystery.

Whether the soul is an immortal essence, an emergent property of the mind, or a concept awaiting full explanation by physics, the inquiry into its mechanics continues to drive philosophical thought and scientific exploration. It forces us to confront the limits of our understanding, the intricate relationship between the physical and the experiential, and the very nature of what it means to be a conscious, feeling being. The mechanics of the soul may forever remain a work in progress, a dynamic interplay between ancient wisdom and cutting-edge discovery, continually reshaping our perception of ourselves and the cosmos.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Plato's Theory of the Soul explained"

YouTube: "Descartes Mind Body Problem Animation""