The Mechanics of the Soul: Unpacking Humanity's Inner Operating System

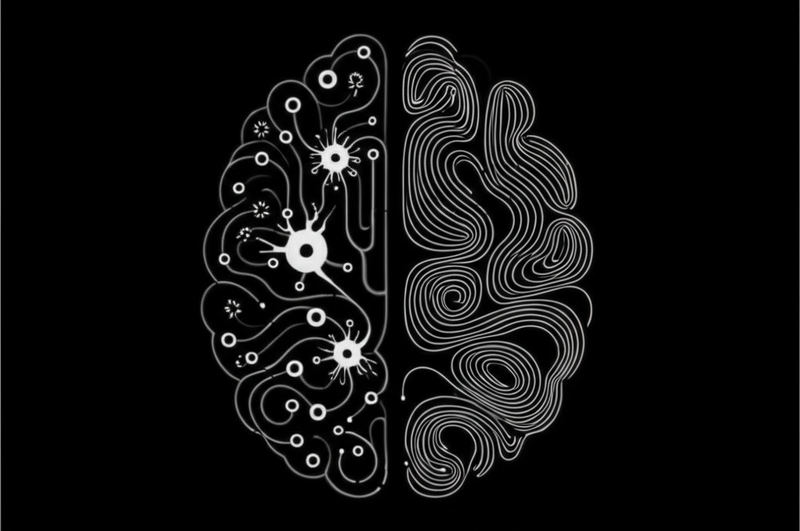

Have you ever paused to wonder, not just what the soul is, but how it actually works? For millennia, philosophers have grappled with the soul, not merely as a concept, but as the very engine of our being. This isn't just about belief; it's about understanding the internal mechanics that drive thought, emotion, and action. From ancient blueprints of consciousness to modern inquiries into the mind and its relationship with physics, the quest to map the soul's inner workings is one of philosophy's most enduring and fascinating journeys. This pillar page explores how the greatest minds of the Western tradition have attempted to deconstruct the soul, seeking to reveal its functions, its components, and its place in the grand scheme of existence.

Ancient Blueprints: The Soul as Form and Function

Before we had neuroscience or cognitive psychology, the great thinkers of antiquity laid the foundational ideas for understanding the soul's operation. They saw it not as a ghost in the machine, but often as the very principle of life and thought itself.

Plato's Tripartite Chariot: A Soul in Motion

Plato, in his Phaedrus, offers perhaps one of the most vivid mechanical metaphors for the soul: a chariot driven by Reason (the charioteer), pulled by two winged horses representing Spirit (noble, spirited emotion) and Appetite (base desires).

- Reason: The guiding force, seeking truth and wisdom, aiming to direct the soul towards the Forms.

- Spirit: The part of us that feels anger, honor, and ambition. It can be an ally to reason or swayed by appetite.

- Appetite: The seat of our basic desires for food, drink, sex, and material comfort.

The "mechanics" here are all about balance and control. A well-ordered soul, according to Plato, is one where Reason successfully guides the spirited and appetitive parts, leading to virtue and harmony. Failure to do so results in internal conflict and disharmony.

Aristotle's Entelechy: The Soul as the Body's Form

Aristotle, Plato's student, offered a more biological and integrated view in De Anima (On the Soul). For him, the soul (psyche) isn't separate from the body but is the form or actualization of a living body. It's what makes a body alive and functional.

Aristotle proposed a hierarchy of souls, each with its own "mechanics" or functions:

- Nutritive Soul (Plants, Animals, Humans): Responsible for basic life functions like growth, reproduction, and metabolism.

- Sentient Soul (Animals, Humans): Encompasses sensation, perception, desire, and movement.

- Rational Soul (Humans Only): The highest form, responsible for thought, reason, and intellect. This is what distinguishes humans.

For Aristotle, the soul is the organizing principle, the blueprint that gives a body its specific life activities. Its mechanics are embedded in the very structure and function of the organism, much like the function of an axe is to cut, and its "soul" is its cutting ability.

The Soul in the Age of Reason: Dualism and Its Discontents

As philosophy progressed, particularly during the Enlightenment, the focus shifted towards individual consciousness and the relationship between the immaterial mind and the material body.

Descartes' Mechanical Universe and the Pineal Gland

René Descartes, a pivotal figure in the Great Books of the Western World, famously proposed a radical mind-body dualism. He saw the universe as a vast machine, governed by mechanical laws. The body was part of this machine, but the soul (or mind) was an entirely distinct, non-physical substance whose essence was thought.

The burning question, of course, was how these two utterly different substances could interact. Descartes famously posited the pineal gland in the brain as the point of interaction, where the immaterial soul could receive sensations from the body and exert its will upon it. This was his attempt to explain the "mechanics" of their interaction, though it raised further questions about how an immaterial entity could affect a material one.

Locke and Hume: Identity, Consciousness, and the Bundle Theory

John Locke, in his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, shifted the focus from a substantial soul to consciousness and personal identity. For Locke, what makes us the same person over time isn't an unchanging substance, but the continuity of consciousness, primarily through memory. The "mechanics" of identity become a matter of an unbroken chain of remembered experiences.

David Hume took this even further. In A Treatise of Human Nature, he famously argued that when he looked inward, he found no persistent "self" or soul, only a "bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement." The "mechanics" of the soul, for Hume, are simply the rapid succession and association of these perceptions, without any underlying, unifying substance.

The Soul and the Moral Compass: Kant's Transcendental Mechanics

Immanuel Kant, another titan of the Great Books, approached the soul from a different angle in his Critique of Pure Reason and Critique of Practical Reason. For Kant, the soul wasn't something we could empirically observe or prove like a physical object. Instead, it emerged as a necessary postulate for understanding human morality and freedom.

Kant argued that to be moral agents, we must be free, and to be free, we must have an immortal soul. The "mechanics" of the soul here aren't about its physical location or interaction with the body, but its role as the transcendental subject that makes experience possible and as the ground for our capacity for moral choice. It's the inner operating system that allows us to reason practically and act according to duty, rather than mere inclination.

Modern Echoes: Mind, Brain, and the Search for "Soul-Stuff"

In the contemporary era, the philosophical inquiry into the "mechanics of the soul" has largely transformed into the philosophy of mind. As neuroscience advances, the relationship between the brain and consciousness becomes increasingly central.

- Is the mind the new soul? Many contemporary philosophers and scientists explore whether the mind is an emergent property of complex brain activity, or if there's something irreducible about conscious experience that goes beyond mere physics and chemistry.

- The Hard Problem of Consciousness: How do physical processes in the brain give rise to subjective experience? This remains a profound challenge, echoing Descartes' interaction problem, but now framed in terms of brain states and phenomenal experience.

- Computational Models: Some theories attempt to describe the "mechanics" of the mind in computational terms, treating the brain as a complex information-processing system.

While the term "soul" might be less common in scientific discourse, the underlying questions about what constitutes our inner life, how it functions, and its relationship to the material world persist. The ancient quest to understand the soul's mechanics continues, now often under the banner of understanding the mind and consciousness.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Philosophy of Mind: Dualism vs. Physicalism Explained"

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "What is Consciousness? The Hard Problem of Consciousness"

Deconstructing the "Mechanics": A Philosophical Toolkit

To truly grasp the diverse "mechanics" proposed for the soul, it helps to categorize the different models and metaphors philosophers have employed:

| Philosophical Model | Primary "Mechanic" or Function | Key Thinker(s) | Metaphorical "Mechanism" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platonic Harmony | Guiding and balancing internal faculties (reason, spirit, appetite) | Plato | Chariot driver managing two horses |

| Aristotelian Actualization | The animating principle; the form of a living body | Aristotle | The blueprint or operating system of an organism |

| Cartesian Interaction | The interface between immaterial thought and material body | Descartes | A junction box (pineal gland) connecting two realms |

| Lockean Continuity | The linking of past and present experiences through memory | Locke | A continuous thread of consciousness |

| Humean Association | The succession and combination of discrete perceptions | Hume | A bundle or kaleidoscope of experiences |

| Kantian Moral Agency | The transcendental ground for freedom, reason, and morality | Kant | An inner engine driving duty and ethical action |

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for the Soul's Operating System

The journey through the "mechanics of the soul" reveals a profound truth: there is no single, universally accepted operating manual. Instead, we find a rich tapestry of thought, each philosopher offering a unique perspective on how our inner world functions. From Plato's charioteer striving for balance, to Aristotle's soul as the very essence of life, to Descartes' perplexing pineal gland, and Kant's moral imperative, the conversation evolves.

The term "mechanics" itself, while evocative, reminds us that human beings have always sought to understand the how alongside the what. Whether we speak of the soul, the mind, or consciousness, the quest to unravel our inner workings continues to be one of philosophy's most vital and engaging pursuits. And perhaps, the beauty lies not in finding a definitive answer, but in the enduring conversation itself, pushing the boundaries of what we can know about ourselves.