The Mechanics of the Heavens: A Philosophical Journey Through Cosmic Order

From the earliest stargazers to the pioneers of modern physics, humanity has been captivated by the celestial dance above. This article explores how our understanding of the mechanics of the heavens has evolved, transitioning from ancient philosophical astronomy rooted in divine order to the precise mathematical physics that underpins our modern view of the world. Drawing heavily from the intellectual lineage found within the Great Books of the Western World, we trace this profound shift, revealing how our cosmic perspective has continually reshaped our philosophical understanding of existence itself.

Looking Upwards, Looking Inwards: The Ancient Quest for Order

For millennia, the night sky presented both a source of wonder and a profound philosophical challenge. How did the stars, planets, and Sun move? What mechanics governed their seemingly eternal paths? Early civilizations, as documented in the foundational texts of the Great Books, sought to impose order on this cosmic spectacle, not merely for practical purposes like timekeeping, but to understand humanity's place within the grand design of the world.

The earliest attempts at celestial mechanics were deeply entwined with cosmology and metaphysics. The heavens were often seen as the realm of the divine, a perfect and unchanging sphere contrasting with the mutable Earth. This philosophical premise dictated the very nature of the observed astronomy.

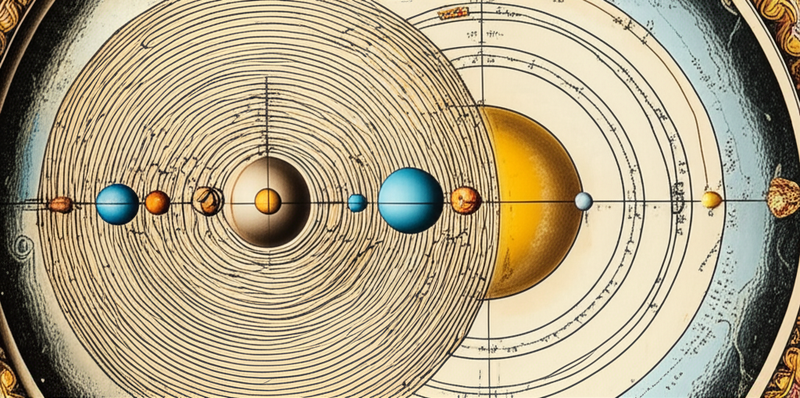

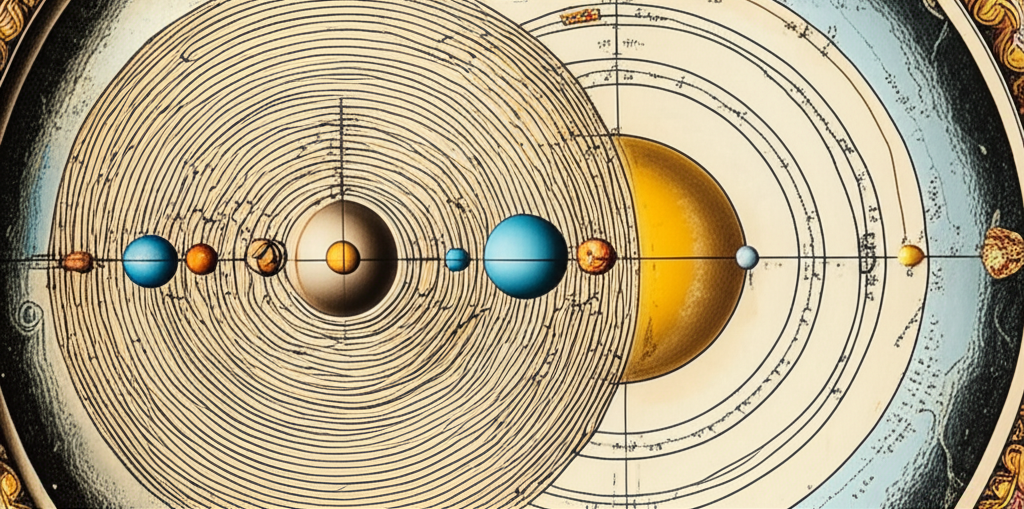

The Geocentric Cosmos: Spheres of Perfection

-

Plato's Ideal Forms: For Plato, the visible heavens were but imperfect reflections of perfect, eternal forms. The ideal motion for celestial bodies was the circle, embodying perfection and unchanging regularity. This philosophical ideal informed subsequent astronomy.

-

Aristotle's Crystalline Spheres: Building on Platonic ideals, Aristotle developed a comprehensive geocentric model. The world was at the center, surrounded by a series of concentric, crystalline spheres, each carrying a celestial body. The mechanics were simple: each sphere rotated uniformly, driven by a Prime Mover, ensuring the eternal, unblemished motion of the heavens. This provided a coherent, albeit Earth-centric, framework for understanding cosmic order, a cornerstone of Western thought for over a millennium.

- Key Features of the Aristotelian Cosmos:

- Geocentricity: Earth is stationary at the center.

- Crystalline Spheres: Invisible, perfect spheres carry the planets and stars.

- Uniform Circular Motion: The ideal and only motion for celestial bodies.

- Divine Impetus: A Prime Mover initiates and sustains motion.

- Sublunar vs. Supralunar: A fundamental division between the imperfect earthly realm and the perfect celestial realm.

- Key Features of the Aristotelian Cosmos:

Ptolemy's Ingenious Refinements: Saving the Phenomena

By the 2nd century AD, the Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, whose Almagest is a landmark in the Great Books, synthesized and refined the geocentric model. While adhering to the core principles of uniform circular motion, Ptolemy introduced sophisticated mathematical devices to account for the observed irregularities in planetary motion, such as retrograde motion.

- Epicycles and Deferents: Planets moved in small circles (epicycles) whose centers moved along larger circles (deferents) around the Earth.

- Equants: A point from which the angular speed of the epicycle's center appeared uniform, further complicating the mechanics but improving observational accuracy.

Ptolemy's system, though incredibly complex, was a triumph of ancient astronomy. It accurately predicted planetary positions for centuries, solidifying the geocentric world view and proving the power of mathematical models, even if built upon flawed philosophical premises.

The Copernican Revolution: A Radical Shift in Perspective

The philosophical and scientific paradigm held by the Ptolemaic system began to crack in the 16th century. Nicolaus Copernicus, another giant whose work graces the Great Books, dared to propose a different mechanics for the cosmos in his De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium.

- Heliocentric Model: Copernicus moved the Sun to the center of the world, with Earth and the other planets orbiting it. This wasn't just a mathematical convenience; it was a profound philosophical challenge.

- Simplified Mechanics: While still employing uniform circular motion and even some epicycles, the heliocentric model offered a more elegant and geometrically simpler explanation for phenomena like retrograde motion. The Earth's own motion naturally explained these observations.

This shift was not immediately embraced. It challenged not only established astronomy but also theological and philosophical doctrines that placed humanity at the physical center of creation. The Copernican revolution was less about immediate observational superiority and more about a new way of thinking about the mechanics of the world.

The Dawn of Celestial Physics: Galileo, Kepler, and the Empirical Turn

The 17th century witnessed a dramatic acceleration in our understanding of celestial mechanics, driven by empirical observation and mathematical rigor, paving the way for modern physics.

- Galileo Galilei's Telescopic Discoveries: Galileo, through his revolutionary use of the telescope, provided direct observational evidence that challenged Aristotelian mechanics and supported the Copernican view. His discoveries, such as the phases of Venus, the moons of Jupiter, and the mountains on the Moon, demonstrated that the heavens were not perfect and unchanging, but dynamic and subject to physical laws. This marked a crucial shift from purely philosophical astronomy to observational physics.

- Johannes Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion: Inspired by Copernicus and working with the meticulous data of Tycho Brahe, Kepler formulated three empirical laws that precisely described the mechanics of planetary orbits.

- Law of Ellipses: Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus. This was a radical departure from the ancient ideal of perfect circles.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time, implying varying orbital speeds.

- Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Kepler's laws provided the definitive mathematical description of planetary mechanics, bridging the gap between descriptive astronomy and predictive physics.

Newton's Grand Synthesis: Universal Mechanics

The culmination of this centuries-long intellectual journey arrived with Isaac Newton, whose Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) stands as one of the most monumental works in the Great Books. Newton unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics under a single, elegant framework.

- Universal Gravitation: Newton proposed that the same force that causes an apple to fall to Earth also keeps the Moon in orbit around the Earth, and the planets in orbit around the Sun. This universal law of gravitation provided the fundamental physics governing all motion in the world.

- Calculus as the Language of the Cosmos: To articulate his laws, Newton developed calculus, a new mathematical tool that allowed for the precise description of change and motion.

- A Clockwork Universe: Newton's mechanics presented a deterministic, predictable cosmos, often likened to a grand clockwork mechanism. Once the initial conditions were known, the future state of the universe could, in principle, be calculated. This had profound philosophical implications, fostering a belief in a rational and knowable world.

Newton's work transformed astronomy into a branch of physics, demonstrating that the mechanics of the heavens were not fundamentally different from the mechanics on Earth.

Beyond Newton: The Evolving Mechanics of the Heavens

While Newton's framework dominated for centuries, the 20th century brought further revolutions in our understanding of cosmic mechanics. Albert Einstein's theories of relativity redefined gravity not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime, offering a more accurate description of the mechanics of massive objects and the universe at large. Quantum mechanics further revealed the bizarre and probabilistic nature of the world at its most fundamental level.

Today, astronomy and physics continue to push the boundaries of knowledge, exploring dark matter, dark energy, black holes, and the origins of the universe. The mechanics of the heavens remain a vibrant field of inquiry, continually refining our understanding of the cosmic world and our place within it.

The Enduring Quest for Cosmic Understanding

The journey from Aristotle's crystalline spheres to Newton's universal gravitation, and beyond to Einstein's spacetime, is a testament to humanity's relentless pursuit of understanding the mechanics of the heavens. This evolution, richly documented in the Great Books of the Western World, is not merely a history of scientific progress; it is a profound philosophical narrative about how we perceive order, causality, and our own significance in the vast cosmic world. Each shift in astronomy has forced us to reconsider fundamental questions about the nature of reality, the limits of knowledge, and the very fabric of existence. The quest continues, driven by the same wonder that first led our ancestors to gaze upwards.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Ptolemaic System vs. The Copernican Model Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Isaac Newton's Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation Explained"