The Mechanics of the Animal Body: A Philosophical Inquiry into Matter and Motion

The animal body, in its astounding complexity and elegant simplicity, has long captivated the minds of philosophers and scientists alike. From the rhythmic beat of a heart to the intricate dance of muscle and bone, living organisms present a profound challenge to our understanding of matter and its organization. This article delves into the philosophical journey of viewing the animal body through a mechanical lens, exploring how various thinkers, drawing from the wellsprings of the Great Books of the Western World, have grappled with the implications of reducing life to the principles of physics. We will trace the evolution of this perspective, from ancient teleology to the radical propositions of the Enlightenment, ultimately examining what it means to consider our very being as an elaborate, yet fundamentally mechanical, system.

The Ancient Roots: Purpose and Physics in the Living Form

For much of antiquity, the understanding of the animal body was inextricably linked to notions of purpose and design. While keenly observant of the physical structures, ancient philosophers sought to understand the why behind the how.

Aristotle's Teleological Mechanics

Aristotle, a titan among the Great Books authors, offered a comprehensive system that, while recognizing the material components of life, ultimately placed emphasis on form and final cause. In his biological treatises, he meticulously detailed the anatomy and physiology of various animal species, observing how organs function in service of the organism's overall existence and reproduction.

- Form and Matter: For Aristotle, the animal body was matter organized by a specific form (the soul). The bones, muscles, and sinews were the matter, but their arrangement and function – their mechanics – were directed towards an inherent purpose, a telos.

- Movement and Growth: He described movement as an inherent capacity, not merely a reaction to external forces. Growth, too, was an internal process guided by the animal's specific nature, rather than a purely chemical accretion of matter.

Even as Aristotle laid the groundwork for empirical biology, his framework resisted a purely reductionist mechanical view, insisting on an internal principle that animated and directed the matter.

The Dawn of the Mechanical Universe: From Organism to Automaton

The Scientific Revolution ushered in a radical shift, increasingly divorcing the study of life from teleology and embedding it firmly within the burgeoning laws of physics. The universe itself began to be seen as a grand machine, and the animal body was no exception.

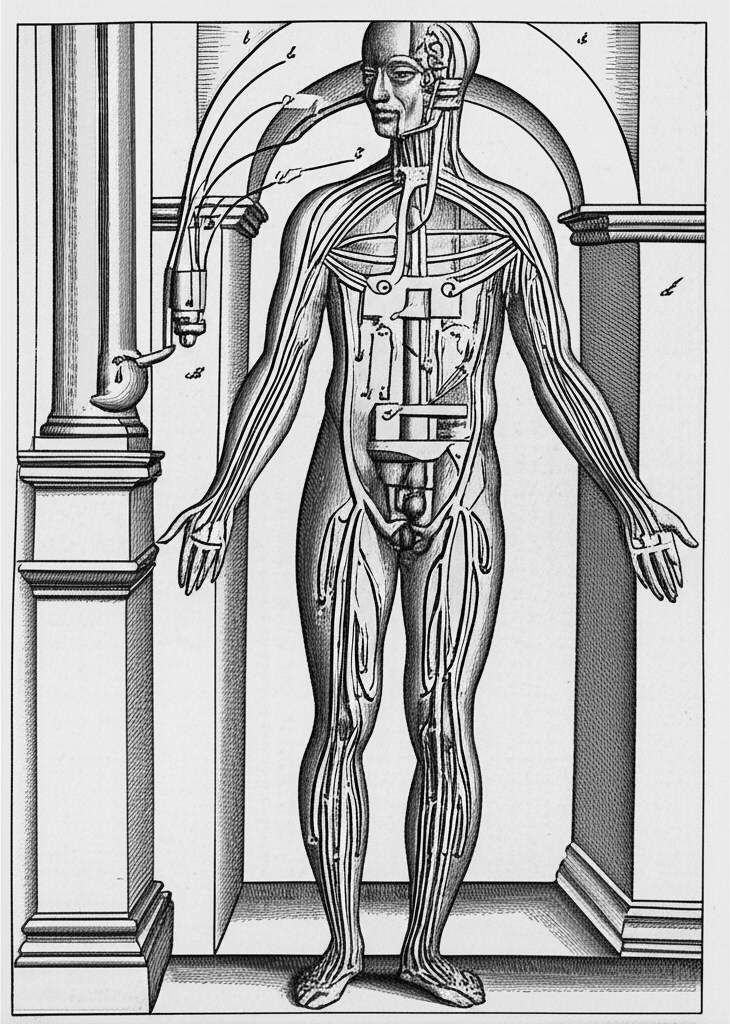

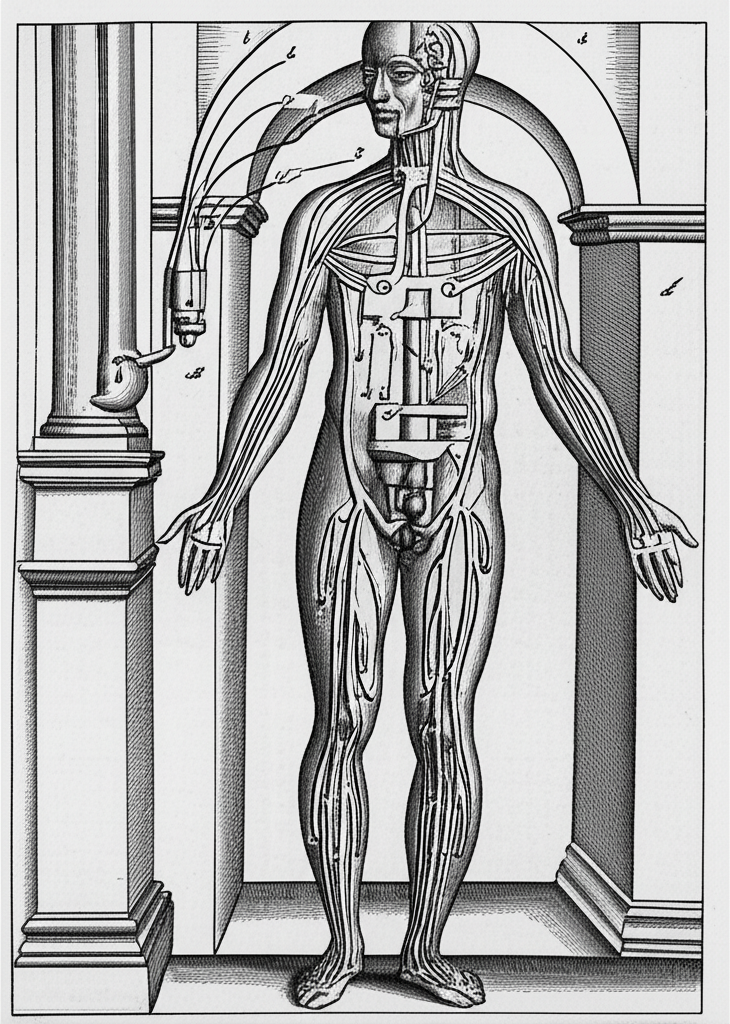

Descartes and the Animal-Machine

Perhaps no figure epitomizes this shift more profoundly than René Descartes. In his Discourse on Method and Treatise on Man, Descartes famously proposed the concept of the animal-machine.

- Res Extensa: For Descartes, the physical world, including animal bodies, was composed of res extensa – extended matter governed by the laws of motion. He argued that all bodily functions – digestion, circulation, respiration, and even involuntary movements – could be explained entirely by mechanical principles.

- Automata: He likened animals to intricate clocks or fountains, complex automata operating without consciousness or a rational soul. Humans, uniquely, possessed a rational soul (res cogitans) distinct from the body, interacting with it at a specific point (the pineal gland). This stark dualism solidified the separation between mind and matter, leaving the body as a purely mechanical entity.

Descartes' vision was revolutionary, providing a powerful framework for studying the body as an object of physics, paving the way for modern physiology and neuroscience.

Galileo, Newton, and the Universal Laws of Physics

The scientific breakthroughs of Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton provided the mathematical and observational tools to solidify the mechanical worldview. Their work demonstrated that the same laws of physics that governed the planets in their orbits also applied to objects on Earth. This universality naturally extended to the animal body.

- Motion and Force: Newton's laws of motion, particularly concerning force, acceleration, and action-reaction, offered a complete language for describing how bodies move, how muscles exert force, and how bones act as levers.

- Gravity and Matter: The concept of gravity, applied to all matter, meant that the weight of an animal body, its posture, and its interaction with the ground could be understood through predictable mechanical interactions.

The success of Newtonian physics in explaining the cosmos profoundly influenced the study of life, encouraging scientists to seek similar elegant, mathematical explanations for biological phenomena.

Dissecting the Mechanical Animal: Systems of Levers, Pumps, and Circuits

With the foundation laid by these philosophical and scientific giants, the subsequent centuries saw an explosion of detailed anatomical and physiological research, all reinforcing the mechanical interpretation of the animal body.

The Body as an Engineering Marvel

When we examine the animal body, we encounter an astonishing array of mechanical solutions to the challenges of survival and movement.

| System | Primary Mechanical Function | Components (Examples) | Related Physics Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal System | Structural support, leverage for movement, protection | Bones, joints, cartilage | Levers, fulcrums, compression, tension |

| Muscular System | Force generation, movement, posture, heat production | Muscles (skeletal, smooth, cardiac), tendons | Contraction, elasticity, torque, work |

| Circulatory System | Transport of nutrients, oxygen, waste; heat distribution | Heart, blood vessels, blood | Pumps, fluid dynamics, pressure, flow |

| Respiratory System | Gas exchange (oxygen in, CO2 out) | Lungs, diaphragm, airways | Pressure gradients, diffusion, elasticity, Boyle's Law |

| Nervous System | Communication, control, sensory input, information processing | Brain, spinal cord, nerves | Electrical impulses, signal transmission, chemical gradients |

Each of these systems, when viewed through the lens of physics, reveals an intricate interplay of forces, pressures, and movements, all orchestrated to maintain the animal's life.

From Reflexes to Complex Behaviors: A Continuum of Mechanics?

The mechanical view suggests that even seemingly complex behaviors might ultimately be reducible to underlying physical and chemical processes. Reflexes, for instance, are clear examples of automatic, mechanical responses to stimuli. But what about conscious decision-making, emotion, or creativity?

This is where the philosophical challenge intensifies. If the animal body is merely a sophisticated machine made of matter, then every action, every thought, every feeling could theoretically be traced back to the physics and chemistry of its components.

Philosophical Implications and Modern Challenges

The enduring legacy of viewing the animal body as a mechanical system continues to shape scientific inquiry and philosophical debate.

The Mind-Body Problem Revisited

If the body is fundamentally a machine, then the question of how consciousness, subjective experience, and self-awareness arise from this matter becomes even more pressing. Is the mind an emergent property of complex mechanical interactions in the brain, or does it represent something fundamentally different, as Descartes suggested? Contemporary philosophy of mind grapples with this daily, often drawing on neuroscience to understand the physical correlates of mental states.

Free Will in a Deterministic Universe

A purely mechanical universe, governed by predictable laws of physics, raises profound questions about free will. If every action is the inevitable outcome of prior physical causes, then where does choice reside? Can an animal machine truly choose, or is its "choice" merely the deterministic output of its mechanical programming? This debate has implications not just for philosophy, but also for ethics, law, and our understanding of responsibility.

Beyond Reductionism: The Limits of Mechanics?

While the mechanical approach has yielded immense understanding, some argue that it might not tell the whole story. Is there an emergent quality to life that cannot be fully explained by simply dissecting its mechanical parts? The concept of holism suggests that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and that life possesses properties that are not present in its isolated matter. This doesn't necessarily contradict mechanics, but rather suggests that new levels of organization might introduce new phenomena.

Conclusion: The Enduring Enigma of the Embodied Self

The journey through the mechanics of the animal body reveals a fascinating interplay between scientific observation and philosophical speculation. From Aristotle's teleological forms to Descartes' radical automata and Newton's universal physics, the endeavor to understand how matter organizes itself into living, moving beings continues to evolve. While the mechanical view has illuminated vast areas of biology and medicine, it simultaneously deepens the philosophical mystery of what it means to be an embodied self. The animal body, in its intricate mechanics, remains a profound testament to the power of physics and the enduring questions it poses about consciousness, purpose, and the very nature of existence.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Descartes Animal Machine Philosophy""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle Biology Teleology""