The Mechanics of the Animal Body: A Philosophical Inquiry

The notion of the animal body as a sophisticated machine, governed by discernible mechanics, is a concept that has captivated philosophers for centuries. From the ancient contemplation of matter and form to the Enlightenment's audacious assertions, understanding the animal body has often served as a battleground for deeper inquiries into the nature of life, consciousness, and the very fabric of existence. This article delves into the historical and philosophical journey of viewing animal physiology through the lens of physics, exploring how this perspective has shaped our understanding of both the non-human world and ourselves, drawing insights from the enduring wisdom contained within the Great Books of the Western World.

I. The Ancient Gaze: Aristotle and the Soul's Architecture

For Aristotle, the study of the animal body was inextricable from the study of its soul. In works like De Anima and Parts of Animals, he meticulously described physiological functions, but always within a teleological framework. The mechanics of digestion, circulation, and movement were not merely random processes of matter in motion; they served a purpose, aiming towards the actualization of the animal's potential.

- Form and Function: Aristotle saw the soul as the form of the body – that which gives it life and its specific capabilities. The body's organs and systems, therefore, are instruments of the soul.

- Hierarchy of Souls: He posited different types of souls: the nutritive (plants), the sentient (animals), and the rational (humans). The animal soul, possessing sensation and locomotion, exhibits complex mechanics driven by an internal principle, rather than purely external forces.

- Physics of Life: While not using "physics" in our modern sense of mathematical laws, Aristotle's natural philosophy sought to understand the inherent principles governing the natural world, including the movement and generation of living matter.

This ancient perspective, while not purely mechanistic, laid foundational groundwork by emphasizing the observable, systematic processes within living beings, prompting later thinkers to either build upon or radically depart from his teleological explanations.

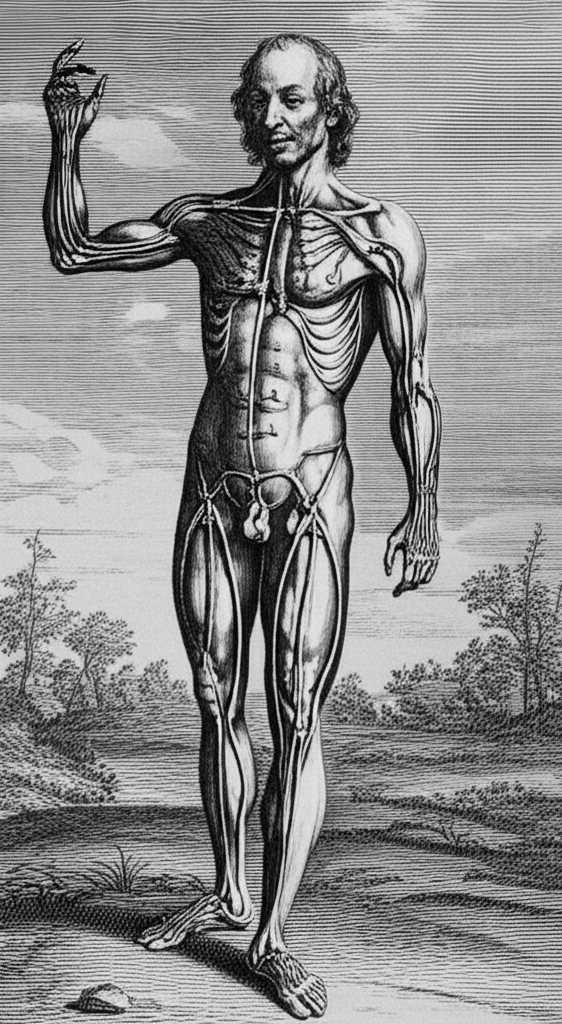

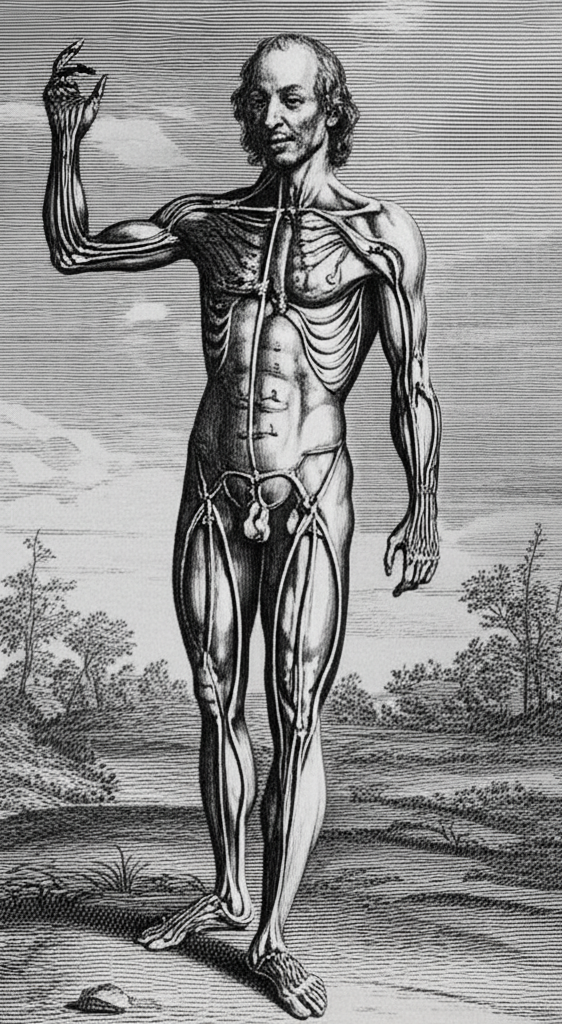

II. Descartes' Clockwork Creatures: The Body as a Machine

The 17th century brought a revolutionary shift, most famously articulated by René Descartes. For Descartes, the mechanics of the animal body, and indeed the human body, were precisely that: the operations of a complex machine. His dualism sharply separated the thinking mind (res cogitans) from the extended body (res extensa).

In Discourse on Method and Treatise on Man, Descartes argued that animals were essentially automata, intricate machines made of matter, operating solely according to the laws of physics. They lacked a rational soul, and their cries of pain were merely mechanical reactions, like a clock striking an hour, not expressions of genuine suffering.

- The Body as a Machine:

- Automaton Analogy: Animals, and the human body, function like elaborate clocks, pumps, or hydraulic systems.

- Physics Governs All: All bodily motions—digestion, circulation, muscle contraction—are explicable purely by the laws of physics and the arrangement of matter.

- No Rational Soul: Animals possess no mind, no consciousness, no true sensation in the Cartesian sense. Their behavior is entirely deterministic.

This radical mechanistic view had profound implications, not only for the burgeoning fields of anatomy and physiology but also for ethics, raising questions about our moral obligations towards creatures deemed mere machines.

III. From Matter to Motion: The Enlightenment and Beyond

The Cartesian vision, while controversial, paved the way for further exploration of the body's mechanics. Enlightenment thinkers, often influenced by the triumphs of Newtonian physics, sought to explain all phenomena, including life, through material causes and efficient mechanics.

- La Mettrie's Man a Machine: Julien Offray de La Mettrie took Descartes' ideas to their logical extreme, arguing in L'Homme Machine (Man a Machine) that even human thought and consciousness were products of complex bodily mechanics, reducible to the organization of matter. This eliminated Descartes' mind-body dualism, proposing a monistic materialism.

- Advances in Physiology: The scientific revolution spurred detailed anatomical and physiological studies, revealing the intricate mechanics of circulation (Harvey), respiration, and nerve impulses. Each discovery seemed to reinforce the idea that life could be understood through its constituent parts and their interactions, much like a finely tuned engine.

This period solidified the materialist approach, emphasizing that the observable physics of matter could account for the complexities of life, moving away from vitalistic explanations that posited an irreducible "life force."

IV. Contemporary Reflections: Bridging the Gap

While modern biology and neuroscience have moved far beyond the simplistic clockwork analogies of Descartes, the fundamental inquiry into the mechanics of the animal body remains central. We now understand the incredible complexity of cellular mechanics, genetic programming, and neural networks, all operating according to physical laws.

The core philosophical tension persists:

- Reductionism vs. Emergence: Can consciousness and subjective experience be fully reduced to the physics and mechanics of brain matter, or do they emerge from complex interactions in a way that transcends mere summation?

- Animal Cognition and Ethics: Scientific studies increasingly reveal sophisticated cognitive abilities, emotional lives, and even cultures in many animal species. This challenges purely mechanistic views and reignites ethical debates about animal rights and welfare, pushing us to reconsider the implications of viewing them solely as biological machines.

The quest to understand the mechanics of the animal body continues to be a fertile ground for philosophical debate, forcing us to confront the boundaries of what physics and matter can explain, and where the mystery of life truly lies.

V. The Enduring Questions

The journey through the philosophical understanding of the mechanics of the animal body leaves us with a series of profound questions that continue to resonate:

- What defines "life" if its processes are entirely mechanical? Is there a qualitative difference between a living organism and a highly sophisticated automaton?

- Where does consciousness fit into a purely mechanistic framework? Can subjective experience, qualia, and self-awareness be fully explained by the physics of neural matter?

- What are the ethical implications of viewing animals as mere machines? How do scientific advancements in animal cognition challenge or reinforce these views?

- Does the pursuit of purely mechanistic explanations diminish the wonder or inherent value of living beings? Or does it reveal a deeper, more intricate beauty in the universe's physics?

These questions, rooted in the historical discourse of the Great Books, continue to shape our philosophical landscape, urging us to constantly re-evaluate our place within the vast, intricate tapestry of life and matter.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Descartes animal machines philosophy" or "Philosophy of animal consciousness""