The Celestial Dance: Unraveling the Mechanics of Planetary Motion

The night sky, a canvas of twinkling lights, has captivated humanity since time immemorial. For millennia, the seemingly erratic yet undeniably rhythmic dance of planets against the backdrop of fixed stars posed one of the universe's most profound riddles. How do they move? Why do they move? And what does their mechanics tell us about the cosmos and our place within it? This pillar page embarks on a philosophical journey through the history of astronomy and physics, exploring how thinkers from the Great Books of the Western World grappled with the quantity and quality of celestial motion, transforming our understanding from a divine ballet to a grand, universal mechanics.

From ancient myth to modern equations, the quest to chart and explain planetary motion is not merely a scientific endeavor; it is a profound philosophical inquiry into order, causality, and the very nature of reality. It's a story of human ingenuity, intellectual courage, and the relentless pursuit of truth, pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible to know about the heavens.

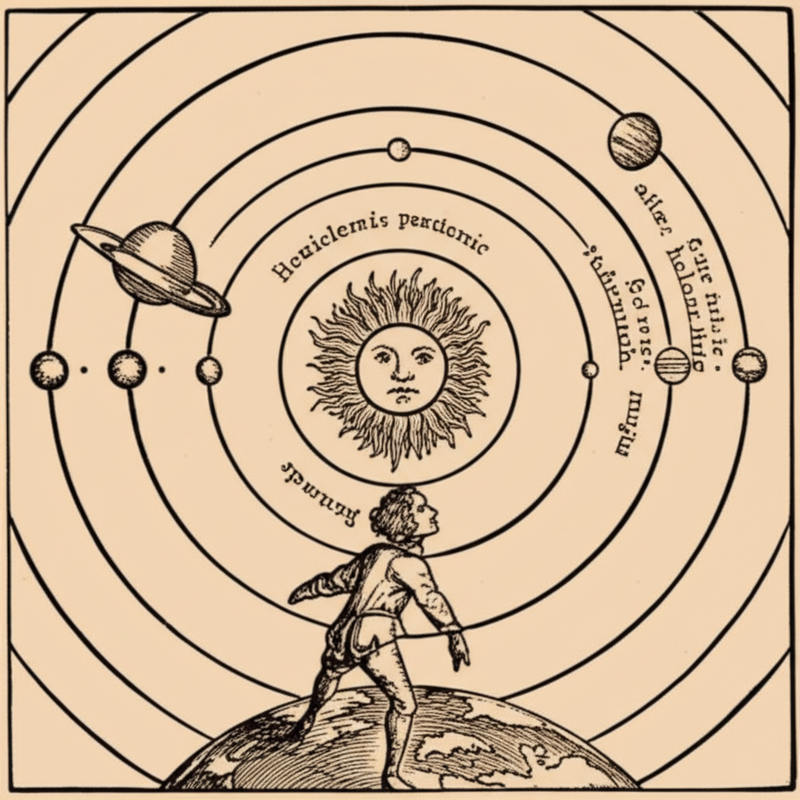

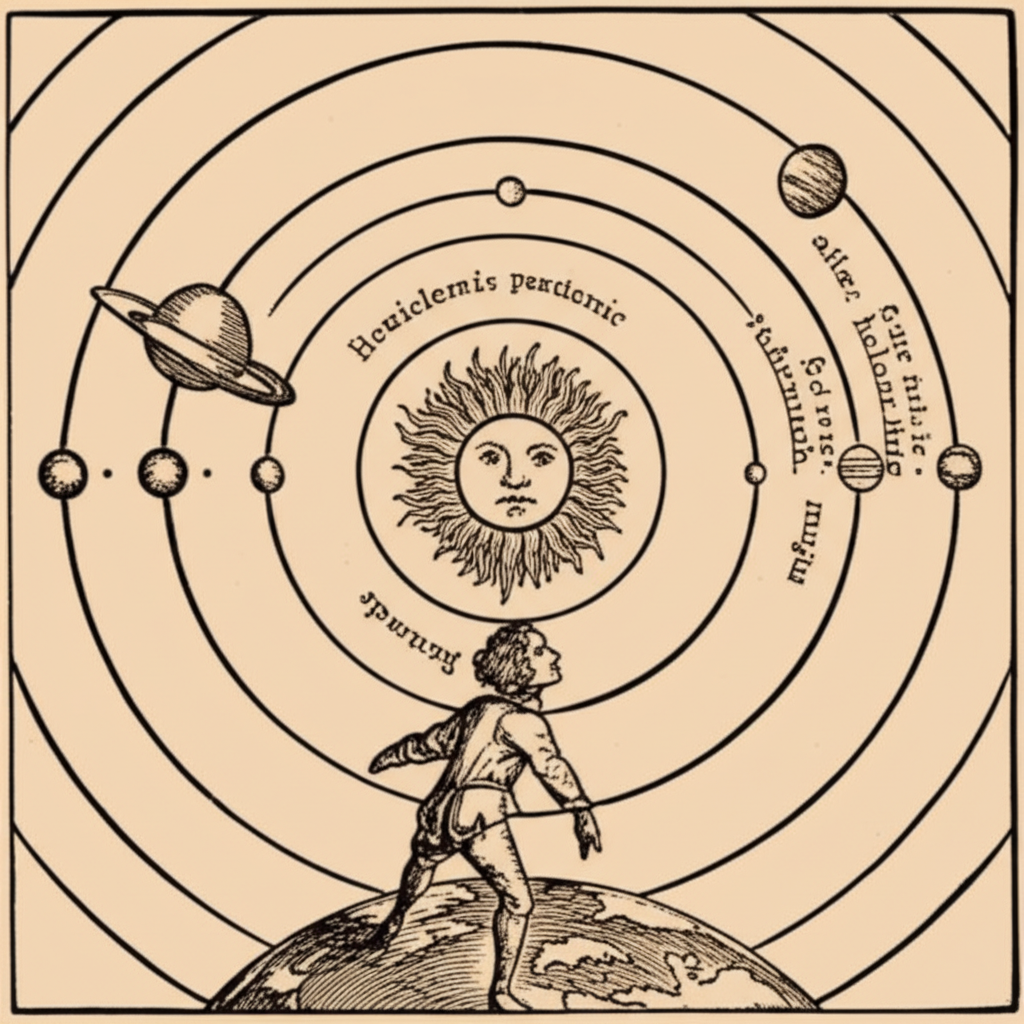

The Ancient Cosmos: A Philosophical Blueprint of Order

Before telescopes and calculus, the mechanics of the heavens were understood through a blend of observation, philosophy, and theological speculation. The visible movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets presented a complex puzzle, which early thinkers attempted to solve by constructing elaborate cosmic architectures.

Aristotle's Spheres and the Celestial Order

For Aristotle, whose ideas profoundly influenced Western thought for nearly two millennia, the cosmos was a series of concentric, crystalline spheres. Earth, imperfect and mutable, lay at the center, while the celestial bodies—perfect and unchanging—were embedded in these spheres, each moving with uniform circular motion. This geocentric model was not just an astronomical theory; it was a complete philosophical system.

- Sublunary vs. Supralunary: The world below the Moon (sublunary) was subject to change, decay, and linear motion, composed of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire). The world above the Moon (supralunary) was eternal, perfect, and composed of a fifth element, the aether, moving only in perfect circles.

- First Mover: The ultimate cause of all motion, for Aristotle, was an unmoved mover, a pure thought that inspired the outermost sphere to rotate, transferring motion inward.

- Philosophical Implications: This model reinforced a hierarchical, ordered universe where Earth was central, humanity was distinct, and the heavens embodied divine perfection. The mechanics were driven by inherent qualities and a desire for perfection, rather than external forces.

Ptolemy's Epicycles and the Challenge of Observation

While Aristotle provided the philosophical framework, Claudius Ptolemy, writing centuries later in his Almagest, developed the most sophisticated mathematical model of the geocentric universe. He inherited Aristotle's general principles but faced a critical challenge: the observable quantity of planetary motion did not perfectly fit simple concentric circles. Planets exhibited retrograde motion—they would periodically appear to stop, move backward, and then resume their forward path.

To account for these irregularities while preserving the principle of uniform circular motion, Ptolemy introduced a series of ingenious devices:

- Epicycles: Smaller circles whose centers moved along larger circles (deferents) around the Earth.

- Eccentrics: Offsetting the center of the deferent from the Earth.

- Equants: Points around which the angular speed of a planet's motion along its deferent appeared uniform, though its speed relative to the deferent's center was not.

Table: Key Concepts in Ancient Planetary Models

| Concept | Description | Primary Proponent | Philosophical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geocentrism | Earth is the stationary center of the universe. | Aristotle, Ptolemy | Humanity's central place, divine order |

| Crystalline Spheres | Invisible, perfect spheres carrying celestial bodies. | Aristotle | Perfection of the heavens, hierarchical cosmos |

| Epicycles | Small circles on larger circles to explain retrograde motion. | Ptolemy | Preserving circular motion, mathematical ingenuity |

| Equant | A point off-center from which angular speed appears uniform. | Ptolemy | Explaining varying speeds while maintaining "uniformity" |

| Aether | The fifth element composing celestial bodies and spheres. | Aristotle | Distinct nature of heavens from Earth |

Ptolemy's system, though incredibly complex, was remarkably successful in predicting planetary positions for over 1400 years. It was a triumph of astronomy and mathematical modeling, even if its underlying physics was ultimately incorrect.

The Copernican Revolution: Shifting Perspectives

The intellectual edifice of the geocentric cosmos, while robust, began to show cracks under the weight of accumulating observational data and the desire for a simpler, more elegant explanation. The challenge came from a Polish canon, Nicolaus Copernicus.

Challenging Geocentrism

In his groundbreaking work, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), published in 1543, Copernicus proposed a radical alternative: a heliocentric model. He argued that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe, and that the Earth itself was a planet, rotating on its axis daily and orbiting the Sun annually.

- Simplicity and Elegance: Copernicus's primary motivation was not necessarily greater accuracy (his model was initially no more accurate than Ptolemy's), but a profound sense of mathematical and aesthetic elegance. Retrograde motion, for instance, became a natural consequence of Earth's motion around the Sun, rather than an elaborate construction of epicycles.

- Order of Planets: The heliocentric model provided a more logical ordering of the planets based on their orbital periods.

The Philosophical Tremors of a Heliocentric Universe

The Copernican model was more than just a change in astronomical mechanics; it was a profound philosophical earthquake.

- Demotion of Earth: Humanity was dislodged from the cosmic center, relegated to a mere planet orbiting a star. This challenged anthropocentric views and forced a re-evaluation of our unique status.

- Questioning Authority: It implicitly questioned the authority of ancient texts and established religious doctrines that had integrated the geocentric model into their worldviews.

- New Questions for Physics: If Earth moves, why don't we feel it? What force keeps us on its surface? What keeps the planets in orbit? These questions laid the groundwork for entirely new branches of physics.

Kepler and Galileo: The Dawn of Empirical Mechanics

The Copernican framework provided a new stage, but the precise mechanics of the play still needed to be written. This task fell to Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei, who ushered in an era where careful observation and mathematical precision began to define astronomy and physics.

Kepler's Laws and the Geometry of the Heavens

Johannes Kepler, a brilliant mathematician and mystic, inherited Tycho Brahe's incredibly precise observational data. Obsessed with finding the mathematical harmonies of the cosmos, Kepler initially tried to fit planetary orbits into perfect circles within Platonic solids. When these attempts failed, he painstakingly analyzed Mars's orbit, leading to his revolutionary three laws of planetary motion:

- The Law of Ellipses: Planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus. This was a radical departure from the ancient dogma of circular orbits.

- The Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This implied that planets move faster when closer to the Sun and slower when further away, introducing a dynamic quantity to their speed.

- The Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period (T) of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis (r) of its orbit (T² ∝ r³). This established a universal mathematical relationship between the periods and sizes of all planetary orbits, revealing a profound underlying mechanics.

Kepler's laws transformed astronomy from describing circular motions to precisely quantifying elliptical paths and varying speeds, laying the mathematical groundwork for a true celestial physics.

Galileo's Telescope and the Imperfection of the Moon

Galileo Galilei, a contemporary of Kepler, championed the Copernican model through direct observation with his improved telescope. His discoveries provided compelling empirical evidence against the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic worldview:

- Mountains on the Moon: The Moon was not a perfect, smooth sphere but had craters and mountains, just like Earth. This challenged the notion of perfect, immutable celestial bodies.

- Phases of Venus: Venus exhibited phases similar to the Moon, which could only be explained if Venus orbited the Sun, not the Earth.

- Moons of Jupiter: The discovery of four moons orbiting Jupiter demonstrated that not everything revolved around Earth, providing a miniature model of a solar system.

- Sunspots: Imperfections on the Sun's surface further refuted the idea of celestial perfection.

Galileo's work, documented in Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), was a crucial step in establishing the empirical method as central to physics and astronomy. He showed that the mechanics of the heavens were not fundamentally different from those on Earth, paving the way for a unified understanding of the universe.

Newton's Grand Synthesis: Universal Mechanics

The stage was set for the ultimate unification. Isaac Newton, building upon the insights of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, provided the comprehensive theoretical framework that would define classical physics for centuries.

Gravity as the Unifying Force

In his monumental work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), published in 1687, Newton articulated the universal laws that govern all motion, both terrestrial and celestial. His most profound contribution was the law of universal gravitation:

- Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

This single law explained why an apple falls to the Earth, why the Moon orbits the Earth, and why the planets orbit the Sun, all under the same mechanics. Kepler's empirical laws were now derived mathematically from a fundamental physical principle. The quantity of gravitational force could be precisely calculated, leading to incredibly accurate predictions.

The Clockwork Universe and its Philosophical Aftermath

Newton's synthesis established a universe governed by immutable, mathematical laws. This vision had profound philosophical implications:

- Determinism: If all motion is governed by precise laws, then the future state of the universe is, in principle, predictable from its present state. This gave rise to the idea of a "clockwork universe," wound up by a divine creator but then running autonomously according to its fixed mechanics.

- God as a Master Mathematician: For Newton, the intricate order and lawfulness of the universe were evidence of a rational and benevolent Creator, a divine architect who designed the cosmos with elegant mathematical precision.

- The Power of Reason: Humanity, through reason and observation, could uncover these divine laws, elevating the status of physics and astronomy as powerful tools for understanding God's creation.

- New Epistemology: The success of Newton's mechanics reinforced the empirical method combined with mathematical deduction as the gold standard for acquiring knowledge, influencing philosophers like Kant and Hume.

Beyond Newton: Modern Refinements and Philosophical Quandaries

While Newton's mechanics provided an astonishingly accurate description of planetary motion, the journey of understanding did not end there. Subsequent observations and theoretical developments have refined and expanded our cosmic perspective.

Perturbations and the Limits of Precision

Even within Newton's framework, the universe proved to be more complex than simple two-body interactions. The gravitational pull of other planets causes slight perturbations in each planet's orbit. The discovery of Uranus, for instance, led to the prediction and subsequent discovery of Neptune, based on its gravitational influence on Uranus's orbit – a triumph of Newtonian mechanics.

However, some anomalies, like the precession of Mercury's perihelion, could not be fully explained by Newtonian physics. These discrepancies ultimately pointed towards the need for an even more profound understanding of gravity and space-time, leading to Einstein's theory of General Relativity in the 20th century. While General Relativity superseded Newton's theory in terms of ultimate accuracy, Newton's mechanics remains incredibly effective for most everyday and astronomical calculations.

The Enduring Philosophical Quest

The story of planetary motion is a testament to the human spirit's insatiable curiosity and its capacity for intellectual growth. From mystical spheres to elliptical orbits and gravitational fields, our understanding of celestial mechanics has continually reshaped our philosophical outlook.

- It has forced us to confront our place in the cosmos, challenging anthropocentric biases.

- It has demonstrated the profound power of mathematical reasoning and empirical observation as tools for knowledge.

- It has raised enduring questions about determinism, free will, the nature of causality, and the role of a divine presence in a law-governed universe.

The mechanics of planetary motion, initially a question of celestial pathways, evolved into a cornerstone of physics and astronomy, profoundly influencing Western philosophy and our understanding of the universe's elegant, quantifiable order. The dance continues, and with it, our philosophical contemplation of its meaning.

YouTube:

- "The History of Astronomy: From Ancient Myths to Modern Science"

- "Newton's Clockwork Universe: Determinism and Free Will in Philosophy"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion philosophy"