The Mechanics of Planetary Motion: A Philosophical Journey Through the Cosmos

The dance of the planets across the night sky has captivated humanity for millennia, inspiring awe, fear, and a profound desire for understanding. "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion" isn't merely a topic for astronomers or physics enthusiasts; it's a cornerstone of Western thought, a narrative of how our understanding of the universe has evolved from philosophical speculation to precise mathematical mechanics. This journey, chronicled in the Great Books of the Western World, reveals humanity's persistent quest to comprehend the quantity and quality of cosmic order, fundamentally reshaping our view of ourselves and our place in the astronomy universe. From the geocentric models of antiquity to Newton's universal laws, the study of planetary motion stands as a testament to the power of observation, reason, and the relentless pursuit of truth.

The Ancient Cosmos: Qualitative Observations and Philosophical Frameworks

For centuries, the prevailing view of the cosmos was deeply intertwined with philosophical and theological beliefs. Ancient Greek thinkers, whose works are foundational to the Great Books of the Western World, sought to understand the heavens through observation and logical deduction, often prioritizing philosophical elegance over empirical mechanics.

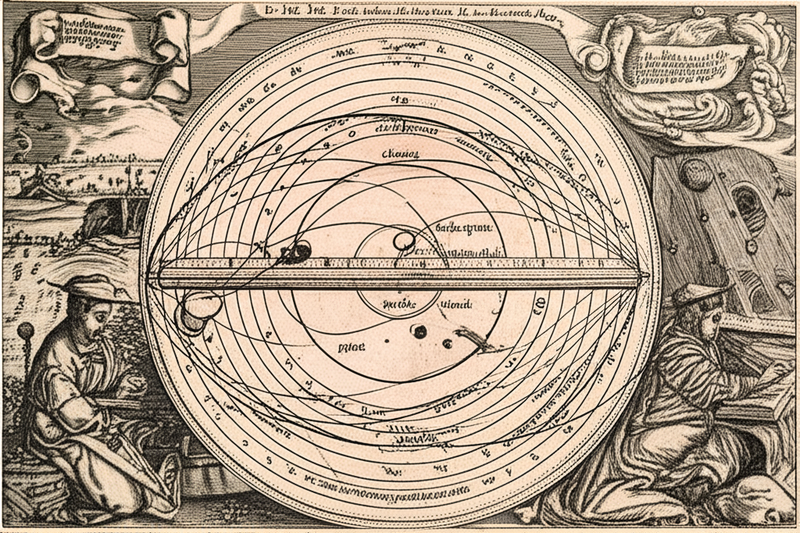

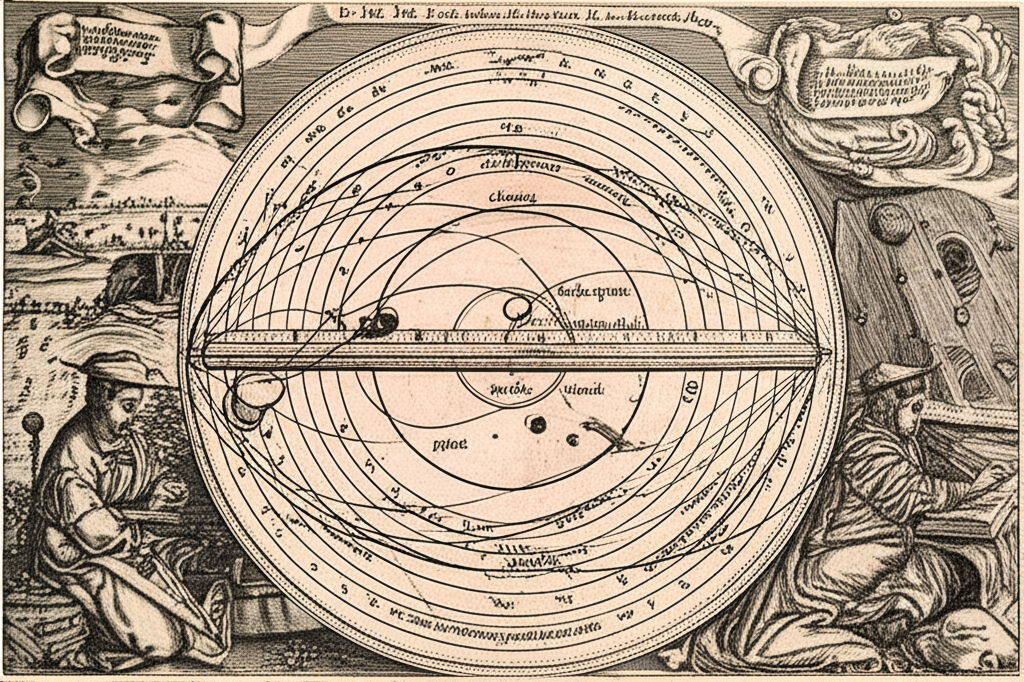

- Aristotle's Geocentric Universe: In works like On the Heavens and Physics, Aristotle proposed a universe where Earth lay immobile at the center, surrounded by crystalline spheres carrying the planets and stars. This model was intuitively appealing, aligning with everyday experience and a philosophical desire for a hierarchical, ordered cosmos. The celestial bodies were considered divine, moving in perfect circles, a testament to their unchanging, incorruptible nature. The mechanics involved were qualitative, driven by a desire for natural place and perfection rather than quantifiable forces.

- Ptolemy's Almagest: Building on earlier Greek astronomy, Claudius Ptolemy's monumental Almagest (c. 150 CE) formalized and refined the geocentric model. To account for the observed retrograde motion of planets – their apparent backward loops in the sky – Ptolemy introduced complex systems of epicycles and deferents. While mathematically ingenious for its time, these additions were descriptive rather than explanatory, aimed at "saving the phenomena" within the geocentric framework. The underlying physics remained largely qualitative, focused on geometric descriptions.

This era was characterized by an understanding of quantity primarily as geometric relationships, with little emphasis on dynamic forces or a unified physics for both terrestrial and celestial realms.

The Copernican Revolution: A Paradigm Shift in Perspective

The 16th century witnessed a radical re-evaluation of the cosmic order, challenging millennia of established astronomy and philosophy.

-

Nicolaus Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model: In his groundbreaking De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), published in 1543 and a pivotal text in the Great Books, Copernicus proposed a heliocentric universe. Placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center simplified the planetary motions, elegantly explaining retrograde motion as a consequence of Earth's own orbit.

Model Central Body Earth's Role Explanation for Retrograde Motion Geocentric Earth Stationary Epicycles and Deferents Heliocentric Sun Orbits the Sun, Rotates Earth's orbital speed relative to other planets

This was more than just a change in astronomical models; it was a profound philosophical shift. It challenged humanity's perceived centrality and spurred a new way of thinking about quantity and observation. However, Copernicus still clung to the ancient Greek ideal of perfect circular orbits, limiting the predictive power of his model.

Kepler's Laws: Embracing Empirical Mechanics and Quantity

The transition from descriptive geometry to predictive physics was significantly advanced by the meticulous observations of Tycho Brahe and the mathematical genius of Johannes Kepler.

- Tycho Brahe's Precision: Brahe, a Danish nobleman, amassed the most accurate pre-telescopic astronomical data over decades. His observations, particularly of Mars, were crucial, as they revealed discrepancies with both Ptolemaic and Copernican predictions.

- Johannes Kepler's Breakthroughs: Working with Brahe's data, Kepler, a profound figure in the Great Books tradition, spent years trying to fit the observations to circular orbits, only to find them consistently off. His struggle led to three revolutionary laws, published in works like Astronomia Nova (1609):

- Law of Ellipses: Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus. This was a radical departure from the ancient ideal of perfect circles, marking a triumph of empirical data over philosophical prejudice.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This introduced the concept of varying orbital speed, with planets moving faster when closer to the Sun.

- Law of Harmonies: The square of a planet's orbital period is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit (P² ∝ a³). This law provided a quantitative relationship between the size of an orbit and the time it takes to complete, hinting at an underlying universal mechanics.

Kepler's laws introduced a new level of quantity and precision to astronomy, transforming it into a predictive science and setting the stage for a unified physics.

Galileo and the Dawn of Modern Physics

While Kepler was describing how planets moved, Galileo Galilei was fundamentally changing how we investigate the natural world, bridging the gap between terrestrial and celestial mechanics.

- The Telescope and Empirical Evidence: Galileo's improvements to the telescope allowed him to make unprecedented observations, documented in works like Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger, 1610). His discoveries – the phases of Venus, mountains on the Moon, and the moons of Jupiter – directly contradicted Aristotelian cosmology and provided strong empirical support for the Copernican model.

- Challenging Aristotelian Physics: In his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632), a seminal text in the Great Books, Galileo championed the scientific method, emphasizing experimentation and observation. He laid the groundwork for modern physics by studying motion, inertia, and gravity, demonstrating that the same physical laws could apply to both Earthly and celestial phenomena, thus dismantling the ancient qualitative distinction between the two realms.

Newton's Universal Gravitation: Unifying Terrestrial and Celestial Mechanics

The culmination of this centuries-long intellectual journey arrived with Isaac Newton, whose work synthesized the observations of Galileo and Kepler into a single, comprehensive system of physics.

- The Principia Mathematica: Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, 1687), another monumental work in the Great Books, presented his three laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

- Laws of Motion: These laws established the fundamental principles of force, mass, and acceleration, providing the quantitative mechanics to describe how objects move and interact.

- Universal Gravitation: Newton proposed that every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers. This single law explained:

- The fall of an apple on Earth.

- The elliptical orbits of planets around the Sun (explaining Kepler's laws).

- The tides.

- The motion of comets.

Newton's work provided a complete, unified physics for both terrestrial and celestial mechanics. It transformed astronomy into a field where precise predictions could be made, based on a few fundamental principles and mathematical quantity. The universe was now seen as a grand, mechanistic clockwork, operating according to immutable laws, a profound philosophical shift.

Beyond Newton: Refining the Mechanics of Motion

While Newton's mechanics provided an astonishingly accurate description of planetary motion for centuries, the 20th century brought further refinements, especially at extreme scales. Albert Einstein's theories of relativity, particularly general relativity, offered a new understanding of gravity not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. This profound insight, while not overturning Newton's practical applications for most planetary motion, offered a deeper philosophical and physics understanding of the universe's fundamental workings, pushing the boundaries of quantity and perception even further.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Cosmic Order

The journey to understand "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion" is a testament to humanity's intellectual evolution. From the qualitative, philosophically driven astronomy of Aristotle and Ptolemy, through the revolutionary insights of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo, to the unifying physics of Newton, we have moved from simply observing the cosmos to quantitatively understanding its intricate mechanics. This narrative, deeply embedded in the Great Books of the Western World, highlights the interplay between observation, mathematical reasoning, and philosophical inquiry. Each step forward not only refined our scientific models but also profoundly altered our perception of reality, demonstrating that the pursuit of quantity in science often leads to qualitative shifts in our philosophical understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Further Exploration

YouTube: "The Newtonian Revolution Great Books of the Western World"

YouTube: "Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion Explained Philosophically"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion philosophy"