The Mechanics of Planetary Motion: A Philosophical Journey Through the Cosmos

Summary: The study of planetary motion stands as a cornerstone of human intellectual endeavor, revealing not only the intricate mechanics of our universe but also profoundly shaping our philosophical understanding of existence, knowledge, and our place within the cosmos. From ancient mythological interpretations to the rigorous mathematical physics of Kepler and Newton, the quest to explain the celestial dance has driven advancements in astronomy and transformed our grasp of natural laws. This journey, rooted in careful observation and the persistent pursuit of quantity, illustrates a fundamental shift in human thought – from a geocentric, qualitative universe to a heliocentric, quantitatively predictable one, forever altering the landscape of philosophy and science.

Unveiling the Celestial Dance: An Introduction

Since time immemorial, humanity has gazed upwards, captivated by the ethereal ballet of stars and planets across the night sky. This celestial spectacle, seemingly erratic yet undeniably regular, has inspired awe, myth, and deep contemplation. Yet, beyond the wonder lies a more profound inquiry: what are the underlying mechanics that govern these vast, luminous bodies? How do they move, and what does their motion tell us about the universe itself?

This pillar page delves into the historical and philosophical evolution of our understanding of planetary motion. It traces the intellectual lineage from early geocentric models, through the revolutionary insights of the Renaissance, to the grand synthesis of classical physics. In doing so, we explore how advancements in astronomy were not merely scientific discoveries but profound philosophical shifts, challenging established worldviews and redefining the boundaries of human knowledge. The relentless pursuit of quantity – measuring, calculating, predicting – has been central to this journey, transforming our qualitative observations into precise, verifiable laws.

From Myth to Astronomy: Early Understandings of the Cosmos

Before the advent of modern scientific inquiry, the heavens were often seen as the realm of deities, their movements imbued with divine purpose or omens. However, even in antiquity, a nascent form of astronomy began to emerge, driven by the practical needs of timekeeping, navigation, and calendrical systems.

The Ancient Cosmos: Earth at the Center

For millennia, the prevailing view, articulated by brilliant minds like Aristotle and refined by Ptolemy, placed Earth firmly at the center of the universe.

- Aristotle's Crystalline Spheres: In works such as Physics and On the Heavens (found within the Great Books of the Western World), Aristotle proposed a geocentric model where celestial bodies were embedded in perfect, crystalline spheres, rotating uniformly around a stationary Earth. This model was philosophically appealing, suggesting a hierarchical and orderly cosmos with humanity at its core. The motion was seen as eternal and perfect, driven by an "unmoved mover."

- Ptolemy's Epicycles: Centuries later, Claudius Ptolemy, in his monumental Almagest (another cornerstone in the Great Books collection), provided the most sophisticated geocentric model. To account for observed retrograde motion (planets appearing to move backward in the sky), Ptolemy introduced complex systems of epicycles (small circles whose centers move along larger circles called deferents). This model, while intricate, allowed for remarkably accurate predictions of planetary positions, a testament to the power of observation and the early application of quantity in describing celestial phenomena, even if the underlying mechanics were flawed.

Philosophical Implications: These early models reinforced a sense of human centrality and cosmic order. The perfection of circular motion was seen as reflective of divine harmony, and the heavens were distinctly separate from the mutable, imperfect Earth. The challenge was to make observation fit the philosophical ideal.

Table 1: Early Geocentric Models

| Thinker | Key Concept | Primary Work (Great Books) | Core Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotle | Crystalline Spheres | Physics, On the Heavens | Earth is stationary at the center. |

| Ptolemy | Epicycles and Deferents | Almagest | Earth is stationary at the center. |

The Copernican Revolution: A Shift in Perspective

The geocentric model, despite its predictive power, was becoming increasingly cumbersome. As astronomical observations became more precise, the number of epicycles needed to explain planetary motion grew, making the model aesthetically and mathematically complex.

Challenging the Earth's Centrality

The 16th century witnessed a paradigm shift that would irrevocably alter our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it.

- Copernicus's Heliocentric Model: Nicolaus Copernicus, in his groundbreaking On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (a pivotal text in the Great Books), proposed a radical alternative: the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe. The Earth, along with the other planets, revolved around the Sun. This heliocentric model offered a simpler, more elegant explanation for the observed movements, particularly retrograde motion, which was now explained by the Earth's own orbital motion relative to other planets.

- The Intellectual Upheaval: This was not merely a scientific adjustment; it was a profound philosophical challenge. It dislodged humanity from its privileged central position, sparking intense debate and controversy, particularly with established religious doctrines. The implications for physics were also immense, demanding new explanations for why objects didn't fly off a moving Earth.

Philosophical Implications: The Copernican revolution initiated a profound re-evaluation of humanity's role in the cosmos. It highlighted the power of mathematical reasoning over sensory perception (the Earth feels stationary) and set the stage for a universe governed by universal laws, rather than anthropocentric design. It ushered in an era where astronomy began to merge more deeply with mathematical physics.

Kepler's Harmony: Mathematical Laws of Motion

While Copernicus offered a new framework, his model still retained circular orbits. It was Johannes Kepler, a brilliant mathematician and astronomer, who truly unlocked the precise mechanics of planetary motion.

Empirical Precision and Mathematical Elegance

Working with the meticulous observational data of Tycho Brahe, Kepler meticulously sought to find the mathematical harmony underlying planetary orbits. His work, particularly Astronomia Nova (another essential Great Book), yielded three revolutionary laws:

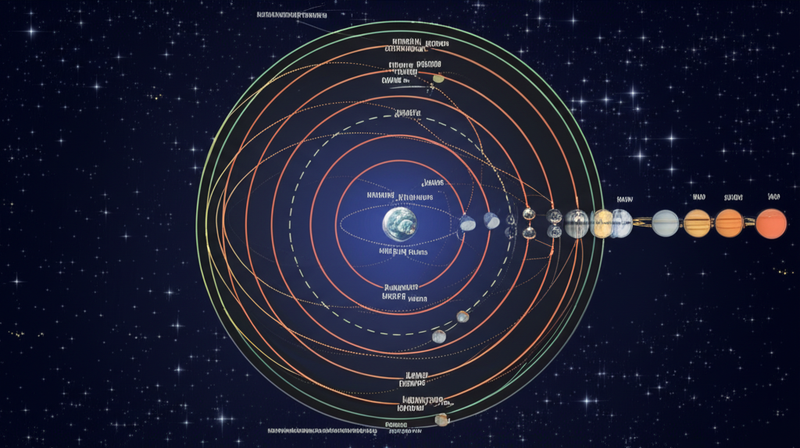

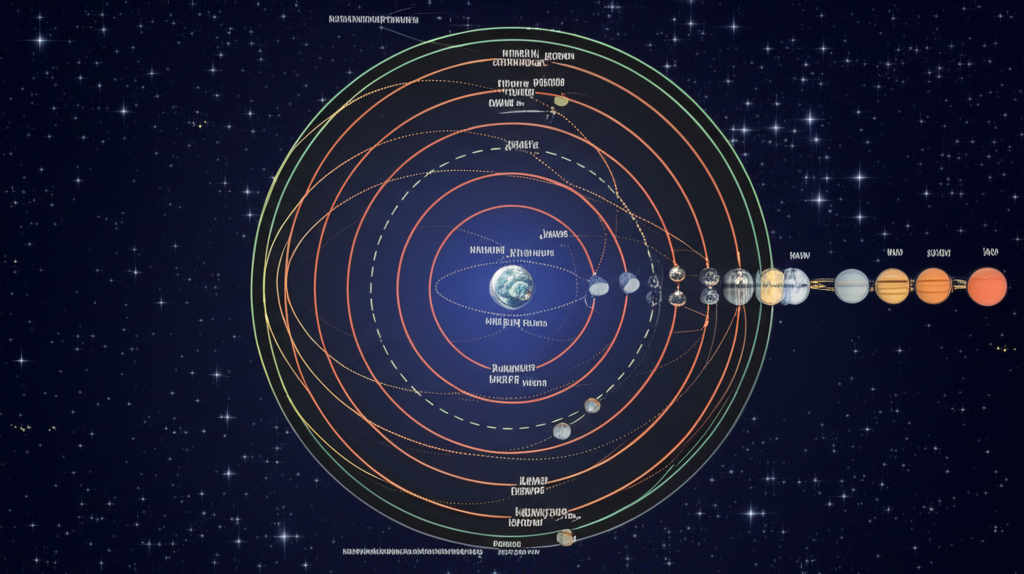

- Law of Elliptical Orbits: Planets move in elliptical orbits, with the Sun at one of the two foci. This challenged the ancient belief in perfect circular motion, showing that the universe was not necessarily conforming to an aesthetic ideal but to a precise mathematical reality.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This implied that planets move faster when closer to the Sun and slower when farther away, introducing a dynamic, non-uniform aspect to their speed.

- Law of Harmonies (Periods): The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. This provided a quantitative relationship between the size of a planet's orbit and the time it takes to complete one revolution, revealing a profound underlying cosmic order.

Philosophical Implications: Kepler's laws demonstrated that the universe operated according to precise, quantifiable mathematical relationships. The "music of the spheres" was not a mystical harmony but a discoverable set of physical laws. This marked a crucial step towards viewing the universe as a grand machine, governed by discoverable mechanics and comprehensible through quantity.

Newton's Synthesis: The Universal Law of Gravitation

The final, grand synthesis that unified celestial and terrestrial physics came with Isaac Newton. His work transformed our understanding of the mechanics of the universe, providing a single, elegant explanation for both an apple falling to the Earth and the Moon orbiting it.

The Grand Unification: Gravity's Embrace

In his monumental Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (often simply Principia, a cornerstone of the Great Books), Newton laid out the foundations of classical physics and the law of universal gravitation:

- Universal Gravitation: Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers. This single law explained Kepler's empirical observations, derived his laws from first principles, and accounted for the tides, the orbits of comets, and the motion of all celestial bodies.

- Calculus as the Language of Motion: Newton developed calculus to articulate these relationships, providing the mathematical tools necessary to describe continuous change and motion. This new mathematical language became indispensable for understanding the intricate mechanics of the universe.

- Three Laws of Motion: Alongside gravitation, Newton's three laws of motion (inertia, F=ma, action-reaction) provided the fundamental principles governing how forces cause objects to move. These laws established the bedrock of classical physics, unifying the mechanics of the heavens and the Earth.

Philosophical Implications: Newton's work cemented the idea of a deterministic, clockwork universe, operating according to immutable natural laws. The universe was seen as a vast, intricate machine, designed by a rational God but operating without constant divine intervention. This had profound implications for theology, free will, and the very nature of reality, shaping Enlightenment thought and beyond. The power of quantity to describe and predict became undeniable.

Modern Astronomy and the Evolving Mechanics

While Newton's mechanics held sway for centuries, providing the framework for space travel and countless technological advancements, the 20th century brought further refinements and new perspectives.

Beyond Classical Physics: The Fabric of Spacetime

Albert Einstein's theories of relativity, while not part of the Great Books of the Western World canon, represent the next major evolution in our understanding of cosmic mechanics. General Relativity reimagined gravity not as a force, but as a curvature in the fabric of spacetime caused by mass and energy. Planets don't orbit the Sun because of an invisible pull, but because they are following the curves in spacetime created by the Sun's immense mass. This more nuanced understanding of physics has allowed for even greater precision in astronomy and has opened up new philosophical questions about the nature of space, time, and causality.

The ongoing quest to understand the mechanics of planetary motion continues, pushing the boundaries of astronomy and physics, from the search for exoplanets to the study of dark matter and dark energy, always driven by the desire to quantify and comprehend the universe's most fundamental workings.

The Enduring Philosophical Questions

The journey through the mechanics of planetary motion is more than a historical account of scientific progress; it is a profound philosophical narrative.

- The Nature of Reality: Is the universe fundamentally rational and ordered, or is its order merely a construct of our minds? The success of physics and astronomy in uncovering predictable mechanics suggests a deep, inherent order.

- The Limits of Human Knowledge: Each new discovery, while answering old questions, invariably raises new ones. The shift from geocentrism to heliocentrism, and then to a relativistic universe, demonstrates the dynamic and evolving nature of scientific truth.

- The Role of Quantity: The transition from qualitative observation to precise quantity – from describing "heavenly perfection" to calculating eccentricities and orbital periods – has been central to our understanding. It highlights the power and utility of mathematics as the language of the universe.

- Humanity's Place: From being at the physical center of creation to a small planet orbiting one of billions of stars, our cosmic address has changed dramatically. This re-evaluation continues to shape our self-perception and our philosophical inquiries into meaning and purpose.

The mechanics of planetary motion, therefore, is not just about how planets move, but about how we, as conscious observers, move through and make sense of the cosmos.

Conclusion: A Universe Unfolding

The story of "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion" is one of intellectual courage, relentless observation, and profound philosophical shifts. From Aristotle's spheres to Newton's universal laws, and on to Einstein's warped spacetime, humanity's understanding of celestial mechanics has consistently reshaped our worldview. It is a testament to the power of human reason, the beauty of mathematical quantity, and the enduring quest to comprehend the physics that govern our universe. As we continue to explore the cosmos, the philosophical questions ignited by this celestial dance will undoubtedly continue to inspire and challenge us, revealing a universe that is ever more intricate, awe-inspiring, and ripe for discovery.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Great Books of the Western World Astronomy Philosophy""

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kepler's Laws Newton's Gravity Explained Philosophically""