The Mechanics of Planetary Motion: A Philosophical Inquiry into Celestial Order

The celestial ballet of planets, a spectacle of enduring wonder, has captivated human imagination since time immemorial. Yet, beyond the aesthetic marvel lies a profound philosophical and scientific journey: the quest to understand the mechanics of their motion. This pursuit, spanning millennia, has not merely charted the paths of distant worlds but has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the universe, the role of physics, and the very nature of knowledge itself. From ancient cosmological myths to Newton's grand synthesis, the study of planetary motion stands as a testament to humanity's relentless drive to quantify, predict, and ultimately comprehend the intricate astronomy of our cosmos. This pillar page delves into the historical and philosophical unfolding of this understanding, revealing how a shift from qualitative observation to rigorous quantitative analysis transformed our perception of the heavens.

I. The Ancient Cosmos: A Sphere of Divine Order

For centuries, the prevailing view of the cosmos was one of ordered perfection, often imbued with divine significance. This geocentric model, eloquently articulated by thinkers within the Great Books of the Western World tradition, placed Earth at the motionless center of the universe.

A. Aristotelian Harmony and Ptolemaic Precision

Aristotle, in his On the Heavens, proposed a universe composed of concentric crystalline spheres, each carrying a celestial body. The motion of these spheres was considered eternal and perfect, driven by a Prime Mover. This was a largely qualitative understanding, where the heavens operated under different mechanics than the terrestrial realm.

Ptolemy, building upon this foundation in his Almagest, provided the most sophisticated mathematical model of the geocentric universe. To account for observed planetary retrograde motion, he introduced complex systems of epicycles, deferents, and equants. This system, while incredibly intricate, allowed for remarkably accurate predictions for its time, demonstrating an early, albeit flawed, attempt at quantitative celestial mechanics. The elegance of the circles, though geometrically complex, still spoke to a philosophical preference for perfect, unchanging forms in the astronomy of the heavens.

II. The Copernican Revolution: Reorienting the Universe

The geocentric model, despite its predictive power, grew increasingly cumbersome. The desire for a simpler, more elegant explanation eventually led to a paradigm shift that challenged not only astronomical dogma but deeply ingrained philosophical and theological beliefs.

A. Copernicus and the Heliocentric Hypothesis

Nicolaus Copernicus, in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), proposed a radical alternative: a heliocentric universe with the Sun at its center and Earth, along with other planets, orbiting it. This daring hypothesis simplified many of the complexities of the Ptolemaic system, offering a more harmonious arrangement.

Copernicus’s work marked a critical step in the evolution of celestial mechanics. While still employing perfect circles for planetary orbits and lacking a physical explanation for why planets would orbit the Sun, it initiated a profound reorientation. It began to shift the focus from Earth-centric observation to a more universal, sun-centered astronomy, laying the groundwork for a truly unified physics of the cosmos. The shift was as much philosophical as it was astronomical, challenging human centrality in the grand scheme of things.

III. Kepler's Laws: The Precision of Quantity Unveiled

The true genius of the Copernican model could only be fully realized through meticulous observation and a new embrace of empirical quantity. Johannes Kepler, inheriting the vast and precise observational data of Tycho Brahe, was the figure who finally broke free from the ancient dogma of circular orbits.

A. The Elliptical Dance and Mathematical Harmony

Kepler's tireless analysis led to three revolutionary laws of planetary motion, published in Astronomia nova and Harmonices Mundi:

- Law of Ellipses: Planets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths, with the Sun at one focus. This was a radical departure from the ancient belief in perfect circles.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This introduced the concept of varying planetary speeds, faster when closer to the Sun.

- Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. This provided a profound quantitative relationship between a planet's distance and its orbital speed, suggesting a universal order.

Kepler's laws transformed celestial mechanics from a descriptive geometric model into a predictive, quantitative physics. He demonstrated that the quantity of observation, when rigorously analyzed, could reveal the underlying mathematical elegance of the cosmos, paving the way for a truly mechanistic understanding of planetary motion.

IV. Galileo and the Dawn of Modern Physics

While Kepler deciphered the geometry of planetary paths, Galileo Galilei laid crucial groundwork for the physics that would explain why planets moved as they did. His contributions bridged the gap between terrestrial and celestial mechanics.

A. Terrestrial Mechanics Meets Celestial Observation

Galileo, a staunch advocate for the Copernican model, utilized the newly invented telescope to make groundbreaking astronomy observations that challenged Aristotelian cosmology. His discovery of Jupiter's moons demonstrated that not everything revolved around the Earth. His observation of the phases of Venus provided compelling evidence for the heliocentric model.

More importantly for the mechanics of planetary motion, Galileo's experiments on falling bodies and his formulation of the principle of inertia, described in Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, were critical. He argued that objects in motion, if undisturbed, would continue in motion. This principle was essential for understanding how planets, once set in motion, could continue to orbit without a constant push, thus dismantling the need for celestial movers and laying the foundation for a unified physics that applied both on Earth and in the heavens. His work was a powerful affirmation of observation and experiment in the pursuit of quantitative understanding.

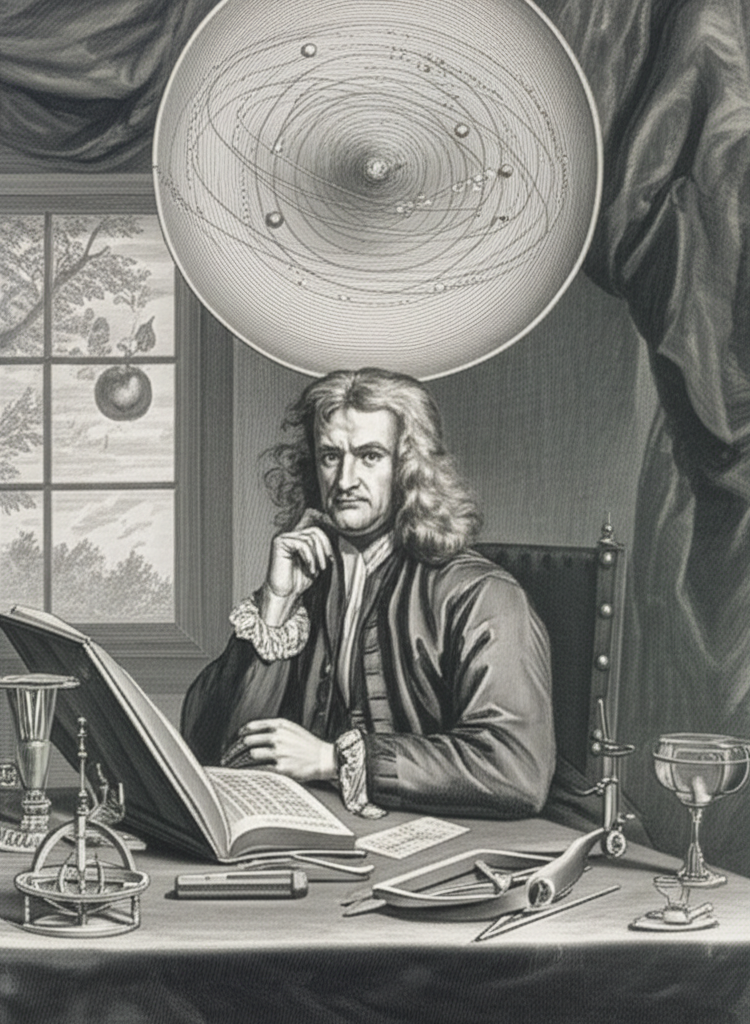

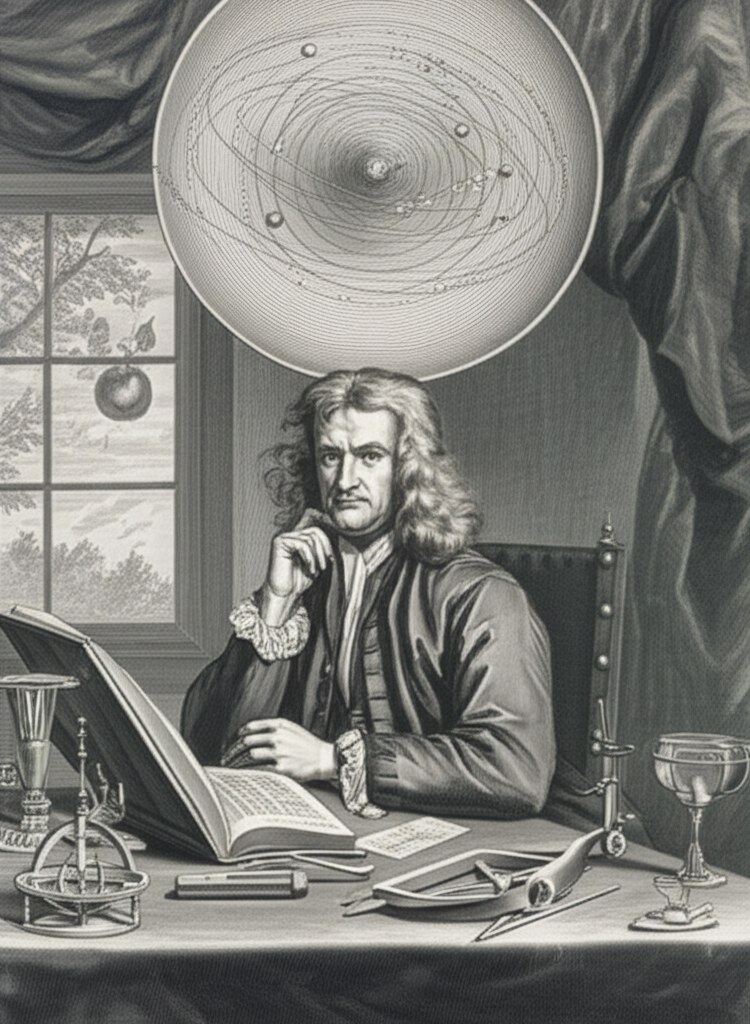

V. Newton's Grand Synthesis: Universal Mechanics

The culmination of these centuries of inquiry arrived with Sir Isaac Newton. His monumental work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics under a single, comprehensive framework.

A. The Unifying Force: Gravity and the Laws of Motion

Newton's three laws of motion, coupled with his law of universal gravitation, provided the ultimate explanation for the mechanics of planetary motion:

- Law of Inertia: An object at rest stays at rest and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force (building on Galileo).

- Law of Acceleration: The acceleration of an object as produced by a net force is directly proportional to the magnitude of the net force, in the same direction as the net force, and inversely proportional to the mass of the object (F=ma).

- Law of Action-Reaction: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Crucially, Newton proposed that the same force that causes an apple to fall to Earth—gravity—is responsible for holding the Moon in orbit around Earth and the planets in orbit around the Sun. He demonstrated that Kepler's empirical laws could be mathematically derived from his universal law of gravitation. This was a triumph of quantitative physics, showing that a single, universal force, calculable with immense precision, governed the entire cosmos. The heavens were no longer qualitatively different from the Earth; they were governed by the same universal mechanics.

Newton's work cemented the idea of a mechanistic, predictable universe, where the motion of every celestial body could, in principle, be calculated with exquisite quantity and precision. This deterministic view profoundly influenced Enlightenment philosophy, suggesting a universe that operated like a grand, intricate clockwork.

VI. Philosophical Reverberations and Modern Astronomy

The journey to understand the mechanics of planetary motion has left an indelible mark on philosophy and science. The triumph of quantitative physics in describing celestial mechanics led to both a profound sense of human intellectual capability and new philosophical dilemmas.

A. From Determinism to the Evolving Cosmos

The Newtonian universe, with its predictable laws, fostered a sense of determinism. If all forces and initial conditions were known, the future state of the universe could, theoretically, be predicted. This raised questions about free will, divine intervention, and the ultimate nature of reality.

However, subsequent developments in astronomy and physics have refined this mechanistic view. Einstein's theory of general relativity, for instance, offered a new understanding of gravity not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime itself, leading to more accurate predictions for extreme gravitational phenomena and a deeper philosophical understanding of space and time. Quantum mechanics at the subatomic level introduced probabilistic elements, challenging strict determinism.

Despite these advancements, the legacy of understanding planetary mechanics remains central. It taught us the power of observation, the elegance of mathematics, and the profound interconnectedness of the cosmos. It transformed astronomy from myth to science and established physics as the fundamental language of the universe. The questions it raised about order, predictability, and humanity's place in the vast expanse continue to inspire philosophical inquiry.

**## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Newton's Laws of Motion Explained" and "Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion Animation""**

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Celestial Understanding

The journey from Aristotle's crystalline spheres to Newton's universal gravitation is a saga of intellectual courage, meticulous observation, and the relentless pursuit of quantity in understanding the mechanics of the cosmos. It is a story woven through the fabric of the Great Books of the Western World, illustrating humanity's profound capacity to unravel the most complex puzzles. The physics of planetary motion is not merely a collection of formulas; it is a testament to the evolving nature of human knowledge, demonstrating how a rigorous, quantitative approach to astronomy can transform our philosophical outlook on the universe and our place within its grand design. The celestial dance continues, and with it, our unending quest to understand its deepest mechanics.