The Mechanics of Planetary Motion: A Philosophical Inquiry

The dance of the planets across the night sky has captivated humanity since time immemorial, inspiring awe, fear, and profound philosophical contemplation. Far from being a mere exercise in astronomy or physics, understanding the mechanics of planetary motion represents one of the most significant intellectual journeys in Western thought. It is a story of shifting paradigms, from qualitative, divinely ordered cosmos to a universe governed by precise, universal laws of quantity and force. This pillar page explores this remarkable evolution, tracing the path from ancient philosophical speculation to the sophisticated mathematical models that define modern mechanics, revealing how each step reshaped our understanding of reality itself.

From Celestial Spheres to Universal Laws: A Journey Through Cosmic Understanding

Our quest to comprehend the cosmos has been a cornerstone of philosophical and scientific inquiry for millennia. Initially, the movements of celestial bodies were intertwined with theological and metaphysical explanations. Over centuries, however, a profound transformation occurred, driven by meticulous observation, rigorous mathematical reasoning, and a persistent desire to uncover the underlying mechanics of the universe. This journey, chronicled by the great minds featured in the Great Books of the Western World, reveals not just advancements in physics and astronomy, but also a fundamental shift in how we perceive knowledge, causality, and the role of quantity in describing the natural world.

The Ancient Cosmos: A Realm of Philosophy and Observation

Before the advent of modern physics, the cosmos was primarily understood through a philosophical lens, where observation was often interpreted to fit pre-existing metaphysical frameworks.

Aristotle's Crystalline Spheres and the Prime Mover

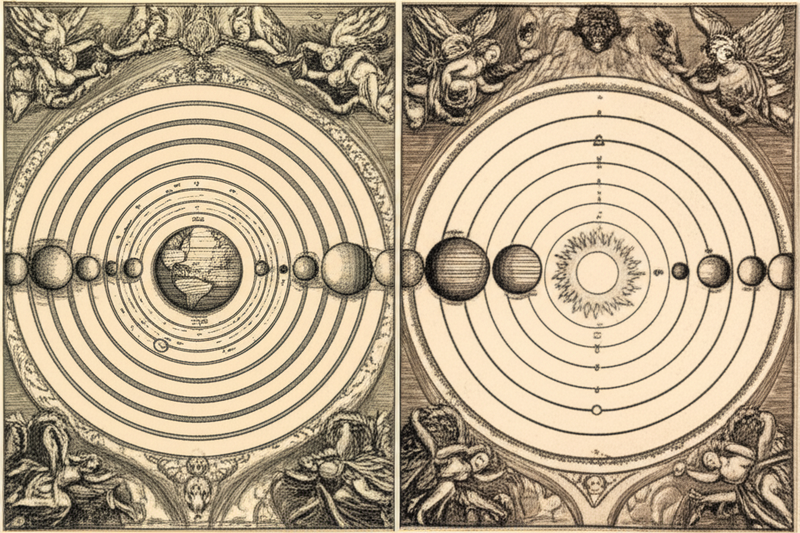

For much of antiquity, the Aristotelian model, detailed in works like On the Heavens, provided the dominant cosmological framework. This geocentric view posited an Earth at the center of the universe, surrounded by concentric, crystalline spheres. Each sphere carried a celestial body – the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and finally, the sphere of the fixed stars. Beyond this lay the Prime Mover, the ultimate cause of all motion, itself unmoved.

- Qualitative Physics: Motion in the heavens was considered perfect, eternal, and circular – a reflection of divine order. Terrestrial motion, by contrast, was imperfect and linear. This was a qualitative physics, where the why (teleology) often superseded the how (mechanisms).

- Astronomy as Description: Early astronomy primarily focused on describing observed phenomena within this philosophical framework, rather than challenging its fundamental assumptions. The mechanics were inherent in the nature of the celestial bodies themselves.

Ptolemy's Ingenious Geometry: Preserving Geocentrism

As observational astronomy improved, the simple Aristotelian model struggled to account for irregularities like retrograde motion (the apparent backward movement of planets). Claudius Ptolemy, in his monumental work Almagest (c. 150 CE), introduced a sophisticated mathematical system to preserve the geocentric view while explaining these complex motions.

- Epicycles, Deferents, and Equants: Ptolemy proposed that planets moved in small circles called epicycles, whose centers in turn moved along larger circles called deferents around the Earth. To further refine the model and match observations, he introduced the equant, an imaginary point from which the center of the epicycle appeared to move at a uniform angular speed.

- Increasing Mathematical Quantity: Ptolemy's system was a triumph of mathematical ingenuity. It demonstrated the power of quantity to describe complex phenomena, even if the underlying mechanics were still based on a philosophically entrenched (and ultimately incorrect) premise. It allowed for surprisingly accurate predictions, despite its increasing complexity.

Re-Centering the Universe: Copernicus and the Heliocentric Hypothesis

The geocentric model, though mathematically sophisticated, was becoming unwieldy. The desire for a simpler, more elegant explanation spurred a profound shift in perspective.

Copernicus's Revolution: A Bold New Arrangement

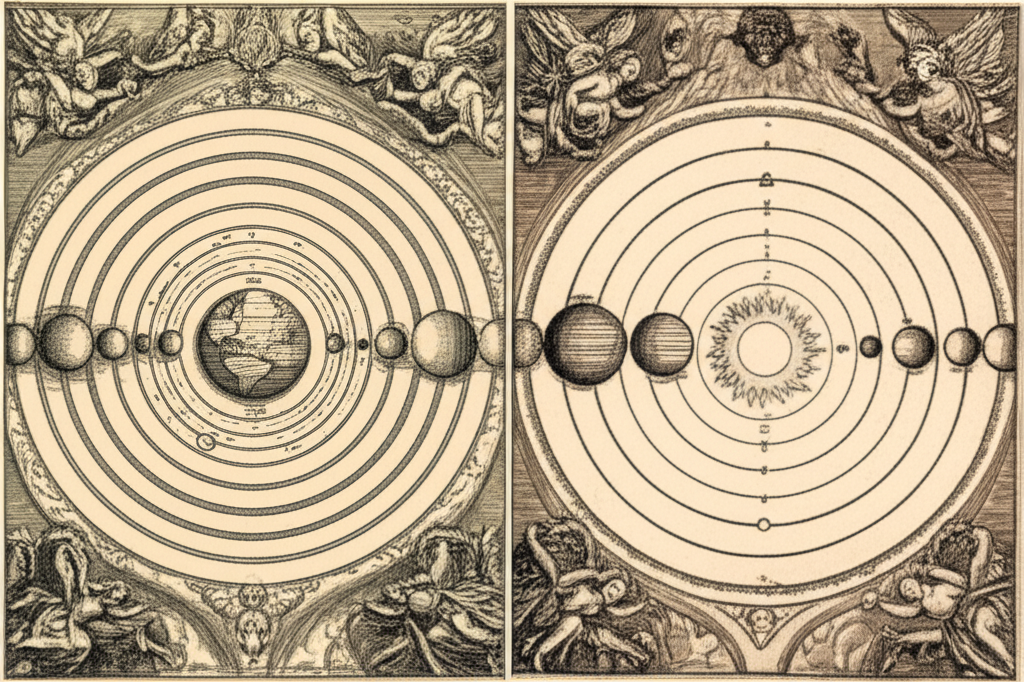

Nicolaus Copernicus, in De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (1543), proposed a radical alternative: a heliocentric universe where the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center.

- Philosophical Elegance: Copernicus's model offered a more harmonious and aesthetically pleasing arrangement. Retrograde motion, for instance, was no longer an intrinsic planetary oddity but a natural consequence of Earth's own orbital motion relative to other planets.

- Challenging Established Physics: This was more than just a change in astronomical models; it was a profound challenge to Aristotelian physics and the prevailing philosophical understanding of the cosmos. If the Earth moved, why did we not feel its motion? Why did objects fall straight down, rather than being left behind? The mechanics of this new universe required new explanations.

The Elliptical Dance: Kepler's Laws and the Power of Data

The Copernican model was a significant conceptual leap, but it still assumed perfectly circular orbits, leading to continued reliance on epicycles to match observations. It took the genius of Johannes Kepler, building on vast amounts of empirical data, to truly unlock the mechanics of planetary motion.

Tycho Brahe's Legacy and Kepler's Insight

Kepler inherited the meticulous, long-term astronomy observations of Tycho Brahe, the most accurate naked-eye astronomer of his time. With this unprecedented wealth of quantity (data), Kepler spent years in arduous calculation, attempting to fit the observations to circular orbits, and failing. This failure led to his groundbreaking discoveries.

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion:

In his Astronomia Nova (1609) and Harmonices Mundi (1619), Kepler articulated three revolutionary laws:

- The Law of Ellipses: Planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one of the two foci. This shattered the ancient dogma of perfect circular motion and marked a crucial step in understanding the true mechanics of celestial movements.

- The Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. This implied that planets move faster when they are closer to the Sun and slower when they are farther away, introducing a dynamic element to their mechanics.

- The Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period (P) of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis (a) of its orbit (P² ∝ a³). This law established a precise, mathematical relationship (a quantity relationship) between the size of a planet's orbit and the time it takes to complete it, suggesting a universal order.

Kepler's laws moved beyond mere description to provide a powerful, quantitative framework for predicting planetary positions. They were empirical laws, derived directly from observation, marking a significant triumph of observational astronomy and mathematical physics.

Gravity's Embrace: Newton's Unifying Principles

Kepler's laws described how planets moved, but not why. The ultimate synthesis, providing the underlying mechanics and the universal physics, came from Isaac Newton.

The Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation

In his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), Newton presented a unified system that explained both terrestrial and celestial motion.

- Newton's Laws of Motion:

- An object at rest stays at rest, and an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced force (Inertia).

- The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass (F=ma).

- For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

- The Law of Universal Gravitation: Every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers (F = G(m₁m₂/r²)).

Newton's genius lay in demonstrating that the same force that causes an apple to fall to Earth also keeps the Moon in orbit and the planets revolving around the Sun. He showed that Kepler's empirical laws were direct consequences of his universal law of gravitation and laws of motion. This was the birth of truly universal mechanics and physics, where quantity became the language of the cosmos.

Philosophical Implications of a Mechanical Universe

Newton's synthesis had profound philosophical implications:

- A Clockwork Universe: The universe was now viewed as a grand, deterministic machine, operating according to immutable laws. This raised questions about free will, divine intervention, and the nature of causality.

- The Triumph of Quantity: The success of Newtonian physics solidified the idea that the universe could be understood and predicted through precise mathematical quantity. This shifted philosophical inquiry towards empiricism and rationalism, emphasizing observation and mathematical reasoning.

- The Role of God: While Newton himself was deeply religious, seeing God as the "Divine Watchmaker" who set the universe in motion, later philosophers questioned the necessity of continuous divine intervention in a self-regulating, mechanical system.

Modern Mechanics and the Evolving Cosmos

Newtonian mechanics remained the unchallenged paradigm for centuries, accurately predicting the motions of planets, moons, and comets. However, as precision astronomy increased, tiny discrepancies emerged.

- Einstein and General Relativity: Albert Einstein's theory of General Relativity (1915) offered a new understanding of gravity, not as a force, but as a curvature of spacetime caused by mass and energy. This provided a more accurate description of phenomena like the precession of Mercury's orbit, which Newtonian physics could not fully explain. While General Relativity superseded Newton's laws in extreme conditions (high gravity, high speeds), Newtonian mechanics remains incredibly accurate and practical for most everyday and astronomical calculations.

- Ongoing Inquiry: The journey continues. Modern physics and astronomy delve into the mechanics of black holes, dark matter, dark energy, and the very fabric of spacetime. These inquiries continue to challenge our philosophical understanding of quantity, reality, and the limits of human knowledge.

The evolution of our understanding of planetary motion is a testament to the power of human intellect – a relentless pursuit of truth that has continually refined our perception of the universe and our place within it. From the qualitative musings of ancient philosophers to the quantitative precision of modern physics, the mechanics of the cosmos remain a fertile ground for both scientific discovery and profound philosophical reflection.

YouTube: "Great Books of the Western World planetary motion"

YouTube: "Philosophy of science Newton Kepler Galileo"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Mechanics of Planetary Motion philosophy"