The Celestial Ballet: Unveiling the Mechanics of Astronomical Bodies

The universe, in its breathtaking expanse, has forever beckoned humanity to comprehend its intricate dance. This article delves into the historical and philosophical journey of understanding the mechanics of astronomical bodies, tracing the evolution from ancient, qualitative observations to the sophisticated, quantitative physics that underpins modern astronomy. From the crystalline spheres of antiquity to the universal gravitation of Newton, we explore how humanity grappled with the celestial order, fundamentally reshaping our view of the cosmos and our place within it. It is a story not merely of scientific discovery, but of profound philosophical shifts in how we perceive reality and the very nature of knowledge.

From Cosmic Harmony to Mechanical Laws: An Overview

For millennia, the celestial realm was largely viewed through a lens of divine order and inherent purpose, a subject of philosophical contemplation as much as empirical observation. The mechanics of the heavens were often described qualitatively, imbued with perfect circular motion and a fixed, unchangeable nature. However, as inquiry deepened, driven by a relentless pursuit of understanding, this perspective gradually yielded to a more rigorous, mathematical approach. The transition from a qualitative understanding to a quantitative one marked a pivotal moment, transforming astronomy into a discipline deeply rooted in physics, where the precise quantity of motion and force became paramount.

Ancient Conceptions: The Philosophical Framework of Celestial Motion

Before the advent of modern science, the understanding of celestial mechanics was inextricably linked to philosophical and cosmological frameworks. Within the traditions reflected in the Great Books of the Western World, figures like Aristotle posited a geocentric universe where celestial bodies moved in perfect circles on concentric, crystalline spheres.

- Aristotelian Cosmology:

- Qualitative Motion: Celestial bodies, being divine and incorruptible, moved in perfect, eternal circles, distinct from the imperfect, linear motion observed on Earth.

- Prime Mover: The ultimate cause of all motion, including the celestial, was an unmoved mover, a purely philosophical concept.

- Spherical Harmony: The arrangement of spheres was often associated with a harmonious, ordered cosmos.

This view, further refined by Ptolemy in his Almagest, provided a remarkably accurate predictive model for its time, despite its fundamental inaccuracies regarding the true mechanics of the solar system. The emphasis was less on universal physical laws and more on a teleological understanding of the cosmos, where everything had its natural place and purpose.

The Copernican Revolution: A Shift in Perspective

The 16th century witnessed a monumental paradigm shift, often referred to as the Copernican Revolution, which challenged the long-held geocentric model. Nicolaus Copernicus, in his De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, proposed a heliocentric model, placing the Sun, not the Earth, at the center of the universe.

Key Impacts of Copernicus's Model:

- Re-evaluation of Mechanics: While Copernicus still retained perfect circular orbits, his model necessitated a radical rethinking of the mechanics involved, even if the underlying physics were not yet fully articulated.

- Philosophical Dislocation: The shift dislodged Earth from its central, privileged position, prompting profound philosophical questions about humanity's place in the cosmos.

- Foundation for Quantitative Astronomy: By simplifying the planetary motions, it paved the way for more precise mathematical descriptions.

Kepler's Laws: Embracing Quantity and Observation

Building upon the meticulous observational data collected by Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler introduced a revolutionary level of quantity and empirical rigor to astronomy. His three laws of planetary motion, published in the early 17th century, abandoned the ancient insistence on perfect circles, revealing the true elliptical nature of orbits.

- Law of Ellipses: Planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus. This was a radical departure from millennia of thought.

- Law of Equal Areas: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time, implying varying orbital speeds.

- Law of Harmonies: The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Kepler's work provided a precise, quantitative description of celestial mechanics, moving beyond mere qualitative descriptions to mathematical laws derived from observation. This was a crucial step towards modern physics.

Galileo and Newton: The Unification of Terrestrial and Celestial Physics

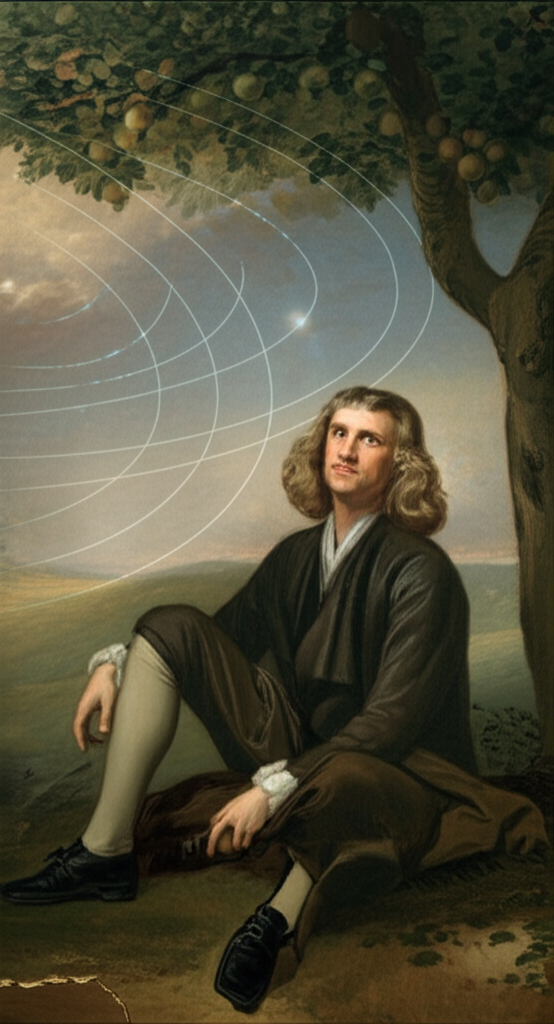

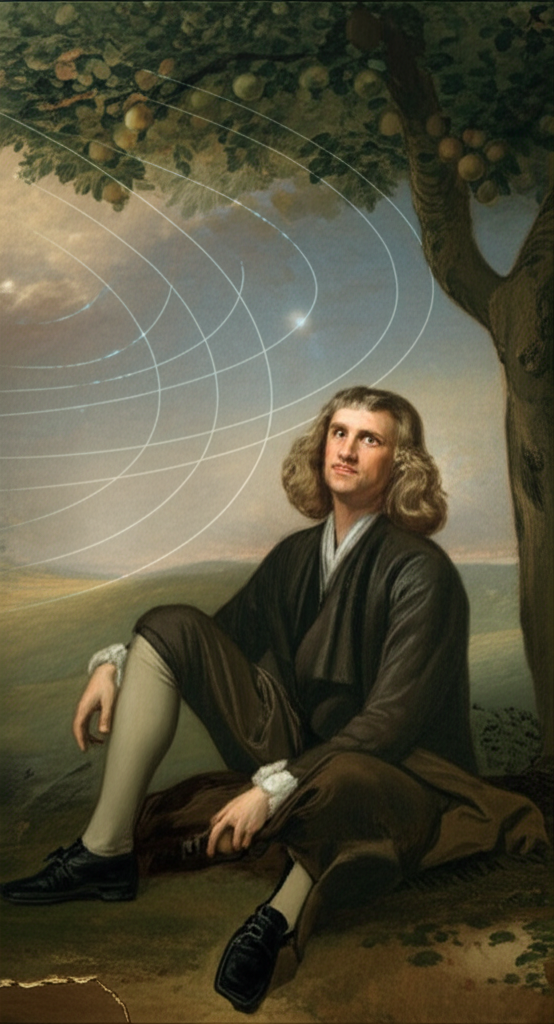

The true unification of terrestrial and celestial mechanics arrived with the groundbreaking work of Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.

-

Galileo Galilei: Through his telescopic observations, Galileo provided compelling empirical evidence supporting the heliocentric model, observing the phases of Venus and the moons of Jupiter. More importantly, his experiments with falling bodies laid the groundwork for modern physics, demonstrating that all objects accelerate at the same rate regardless of mass (in a vacuum), challenging Aristotelian notions. He introduced the concept of inertia, a cornerstone of classical mechanics.

-

Isaac Newton: The culmination of this intellectual journey was Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Newton's universal law of gravitation provided a single, elegant mathematical framework that explained both the falling apple and the orbiting moon.

- Universal Gravitation: Every particle of matter in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

- Laws of Motion: Newton's three laws of motion provided the fundamental principles governing all mechanics, whether on Earth or in the heavens.

- Calculus: To articulate these laws, Newton, alongside Leibniz, developed calculus, a powerful mathematical tool essential for describing continuous change and quantity in physics.

Newton's synthesis irrevocably established that the same physics governed both the terrestrial and celestial realms. The celestial mechanics were no longer a mystery governed by divine will or inherent perfection, but rather by quantifiable, universal laws accessible through reason and observation.

The Enduring Philosophical Implications

The journey to understand the mechanics of astronomical bodies is more than a scientific chronicle; it is a profound philosophical narrative. It forced humanity to confront its anthropocentric biases, to question established dogmas, and to embrace a universe governed by impersonal, quantifiable laws rather than overt purpose. This shift has had lasting repercussions on metaphysics, epistemology, and our understanding of human reason itself.

The transition from qualitative descriptions to precise quantity fundamentally altered the scientific method and our understanding of what constitutes knowledge. It demonstrated the power of mathematical reasoning and empirical observation in uncovering the deep structures of reality, driving the Enlightenment and shaping the modern scientific age.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Great Books of the Western World Astronomy Philosophy""

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Newtonian Mechanics Philosophical Impact""