The Measurement of Time and Space: A Philosophical Journey Through the Cosmos

Summary: The very fabric of our existence—Time and Space—are concepts we instinctively grasp yet struggle to define, let alone measure. This article embarks on a philosophical expedition, tracing how thinkers from antiquity to the modern era, drawing heavily from the Great Books of the Western World, have grappled with these fundamental dimensions. We will explore the evolving understanding of Time and Space not merely as containers for events, but as intertwined ideas deeply rooted in human perception, quantity, and the abstract elegance of mathematics. From Aristotle's qualitative distinctions to Newton's absolute universe, and from Leibniz's relational cosmos to Kant's subjective forms of intuition, we uncover how our attempts to quantify reality reveal as much about the human mind as they do about the universe itself.

Table of Contents

- The Ancient Gaze: Time and Space in Early Philosophy

- Aristotle's Cosmos: Motion, Place, and the Quantity of Being

- The Newtonian Paradigm: Absolute Time and Space

- Leibniz's Relational Universe: Space and Time as Orders of Phenomena

- Kant's Copernican Revolution: The A Priori Forms of Intuition

- Modern Physics and the Redefinition of Reality

- The Enduring Philosophical Challenge: Can We Truly Measure the Immeasurable?

The Ancient Gaze: Time and Space in Early Philosophy

Before the precision of atomic clocks or the grandeur of cosmic telescopes, humanity contemplated Time and Space with a sense of profound wonder and limited tools. How did the ancients perceive these omnipresent, yet elusive, dimensions? Their initial inquiries were less about measurement in a scientific sense and more about understanding the nature of these realities. Plato, in his Timaeus, offered a profound vision of Time as the "moving image of eternity," created alongside the cosmos itself, while Space (or the "receptacle") was the amorphous medium in which all things come into being. Here, Time and Space are not mere metrics, but fundamental principles, inseparable from the very act of creation and existence. They are the stage upon which reality unfolds, though their precise quantity remained elusive, understood more through observation of cycles and extensions than through rigorous mathematics.

Aristotle's Cosmos: Motion, Place, and the Quantity of Being

Few philosophers have shaped our understanding of the natural world as profoundly as Aristotle. In his Physics (a cornerstone of the Great Books of the Western World), he delves deeply into the concepts of Time and Space. For Aristotle, Time is intrinsically linked to motion. He famously defines it as "the number of motion in respect of 'before' and 'after'." This isn't an abstract, independent flow, but a quantity derived from the observable changes in the world. If nothing moves, there is no Time.

Similarly, Aristotle's concept of Space is not an empty void, but rather "place" – the innermost motionless boundary of the containing body. This means Space is always filled; there is no absolute emptiness. The idea of quantity here is relational and embodied. We understand the quantity of Time by counting motions, and the quantity of Space by delineating the boundaries of objects. This qualitative approach, while a precursor to later quantitative science, laid the groundwork for centuries of philosophical and scientific inquiry into the dimensions of our reality.

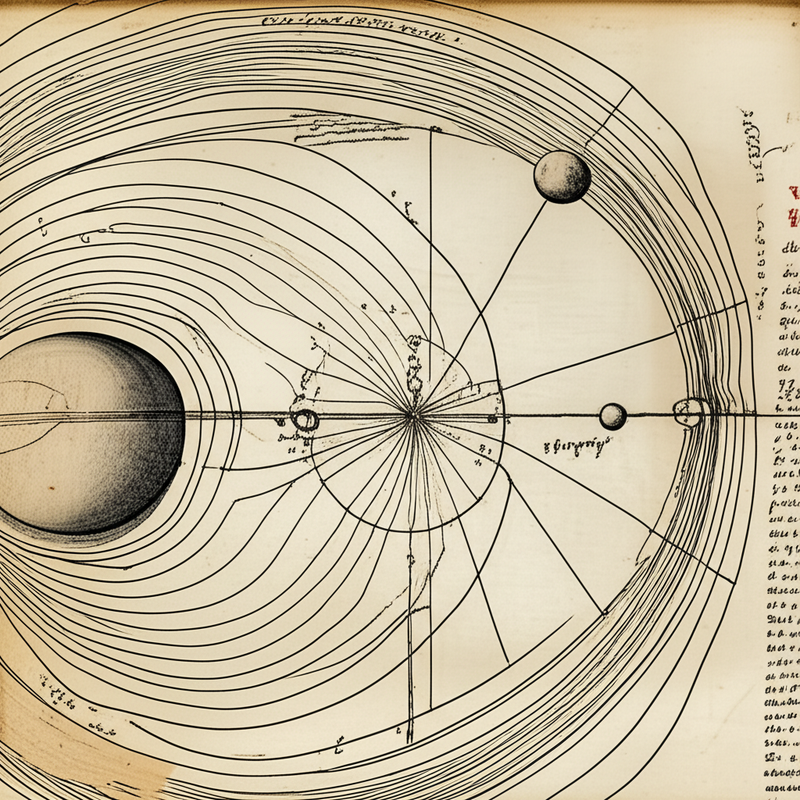

The Newtonian Paradigm: Absolute Time and Space

The scientific revolution, spearheaded by Sir Isaac Newton, dramatically shifted the philosophical landscape regarding Time and Space. In his monumental Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (another essential text from the Great Books collection), Newton presented a universe built upon absolute, independent foundations.

Newton articulated:

- Absolute, true, and mathematical Time: This, he declared, "of itself, and from its own nature, flows equably without relation to anything external." It's a universal clock, ticking uniformly for everyone and everything, everywhere.

- Absolute Space: This, "in its own nature, without relation to anything external, remains always similar and immovable." It's an infinite, fixed stage upon which all events unfold, irrespective of whether anything exists within it.

This vision provided the bedrock for classical physics, where measurement became paramount. The quantity of Time could be precisely measured by mechanical clocks, and the quantity of Space by rulers and geometric principles. Mathematics became the undisputed language of the cosmos, allowing for unparalleled predictions and understanding of celestial mechanics and terrestrial motion. The philosophical implication was clear: Time and Space were objective, universal realities, external to human perception, waiting to be precisely quantified.

Leibniz's Relational Universe: Space and Time as Orders of Phenomena

Not everyone, however, bought into Newton's absolute framework. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a contemporary and intellectual rival, offered a compelling counter-argument, most famously articulated in his correspondence with Samuel Clarke (a defender of Newton), a collection often referenced in discussions of the Great Books. Leibniz fiercely critiqued the notion of absolute Time and Space, arguing that they were not independent substances but rather relational concepts.

For Leibniz:

- Space is the order of co-existence of phenomena. It is not an empty container, but the arrangement of objects relative to one another. If there were no objects, there would be no Space.

- Time is the order of succession of phenomena. It is the sequence of events, not an independent flow. If nothing happened, there would be no Time.

In this view, the quantity of Time and Space is derived from the relations between existing substances and events. To talk of Time or Space without reference to what occupies or happens within them is to speak of nothing at all. This philosophical stance suggests that measurement is always a measurement of relations, challenging the idea of an objective, external framework and emphasizing the interconnectedness of all things.

Kant's Copernican Revolution: The A Priori Forms of Intuition

Immanuel Kant, in his monumental Critique of Pure Reason (another indispensable volume from the Great Books), attempted to bridge the chasm between rationalism and empiricism, and in doing so, revolutionized our understanding of Time and Space. Kant proposed that Time and Space are not properties of objects in themselves, nor are they merely relational concepts derived from experience. Instead, they are a priori forms of human sensibility—inherent structures of the mind through which we perceive and organize all experience.

- We don't perceive Time and Space empirically; rather, we perceive everything in Time and in Space. They are the necessary conditions for any experience to be possible.

- This explains why mathematics, particularly geometry for Space and arithmetic for Time, can yield synthetic a priori truths. Our minds are pre-equipped to structure reality spatially and temporally, making these mathematical disciplines universally valid within our phenomenal experience.

For Kant, the quantity of Time and Space is not something we discover "out there," but something we impose on our perceptions. They are the spectacles through which we view the world, and without them, the world as we know it would be unintelligible. This "Copernican Revolution" placed the human mind at the center of the epistemological universe, profoundly influencing how we understand the limits and possibilities of measurement.

Modern Physics and the Redefinition of Reality

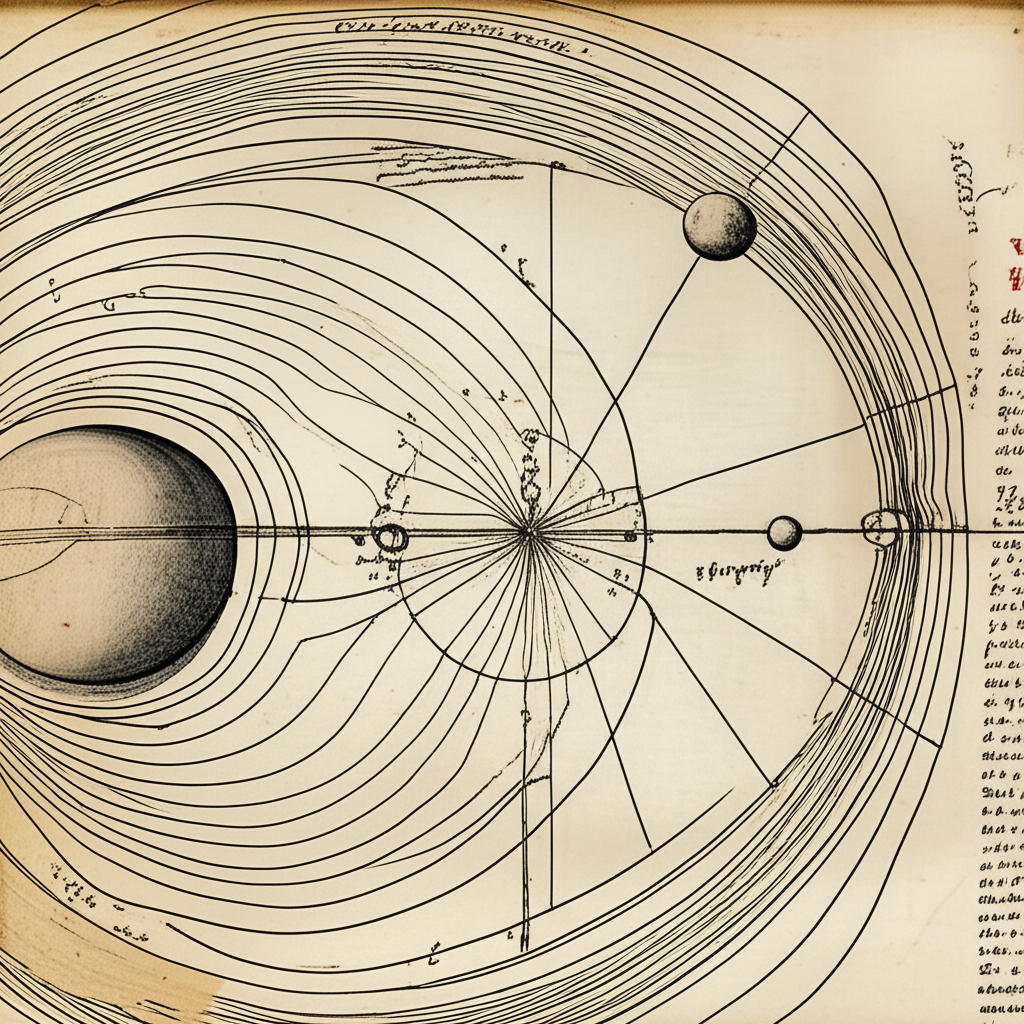

The 20th century ushered in another seismic shift with Albert Einstein's theories of relativity, challenging the Newtonian absolutes and introducing a new paradigm that continues to captivate philosophers and scientists alike. Einstein's special and general relativity demonstrated that Time and Space are not independent entities but are woven together into a single, dynamic fabric called spacetime.

Key takeaways include:

- Relativity of Measurement: The measurement of Time intervals and Space distances is not absolute but depends on the relative motion of the observer. Time dilation and length contraction are not illusions but real physical effects.

- Spacetime Curvature: Mass and energy warp spacetime, and this curvature is what we perceive as gravity. This means Space is not a passive stage but an active participant in the universe's dynamics.

- Mathematics as the Guide: The sophisticated mathematics of differential geometry became indispensable for describing this flexible, interconnected reality.

Further still, quantum mechanics, exploring the smallest scales of existence, hints at a reality where Time and Space might not even be continuous, but discrete, quantized entities – a "quantum of time" or a Planck length representing the smallest possible measurable unit. The philosophical implications are staggering: if Time and Space are emergent properties or fundamentally different at the quantum level, how does this alter our understanding of their very nature and our ability to truly measure them?

The Enduring Philosophical Challenge: Can We Truly Measure the Immeasurable?

Our journey through the philosophical landscape of Time and Space reveals a persistent tension: are these dimensions objective realities to be precisely measured by mathematics, or are they subjective constructs of the human mind, shaping our perception? From Aristotle's qualitative quantity of motion to Newton's absolute framework, Leibniz's relational universe, and Kant's a priori forms, each era has wrestled with the profound implications of these fundamental concepts.

The ongoing dialogue between philosophy and science, particularly with the advent of relativity and quantum mechanics, continues to push the boundaries of what we thought we knew. The very act of measurement is not just a scientific endeavor; it is a philosophical statement about what we believe reality to be. As we continue to refine our instruments and our mathematical models, the deeper questions about the ultimate nature of Time and Space—their origins, their limits, and their true quantity—remain profoundly open, inviting endless contemplation. The quest to understand these fundamental dimensions is, in essence, the quest to understand our place within the cosmos.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Time and Motion Explained""

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Kant's Philosophy of Space and Time Explained""