The Matter of the Body: A Philosophical Inquiry into Our Substance

The human body, that most intimate and immediate of our possessions, presents a profound and enduring enigma to philosophy. What is this physical form we inhabit? Is it merely a collection of inert "matter" arranged in a complex fashion, or does its very substance hold deeper implications for our identity, consciousness, and place in the cosmos? From the ancient atomists to the mechanistic worldviews of the Enlightenment and beyond, the philosophical journey to comprehend the "matter of the body" has been a central thread in understanding "Man." This article delves into how philosophers, often grappling with the evolving understanding of "Physics," have sought to define the corporeal, and what these definitions mean for our understanding of ourselves.

The Enduring Question of Our Substance

At its heart, the inquiry into the matter of the body is an attempt to answer fundamental questions: What are we made of? How does this material composition relate to our thoughts, feelings, and experiences? Is the body merely a container for something non-material, or is it inextricably linked, perhaps even identical, with our very being? These questions have spurred centuries of debate, forcing us to confront the very definition of existence.

From Ancient Atoms to Aristotelian Forms: Early Conceptions of Matter

The earliest Western philosophers grappled with the fundamental stuff of reality. The Pre-Socratics, for instance, sought a physis or primary substance. Democritus, a towering figure in the Great Books of the Western World, proposed that all things, including the human body, are composed of indivisible, unchangeable particles called atoms, moving in a void. This radical materialism suggested that the human form was simply a complex arrangement of these fundamental bits of matter, a view later eloquently articulated by Lucretius.

However, a different perspective emerged with Plato, who, while acknowledging the physical world, posited that the body was an imperfect, transient vessel for the immortal soul. For Plato, true reality resided in the eternal Forms, making the body a potential impediment to genuine knowledge.

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, offered a more integrated view. In his Physics and De Anima, he introduced the concept of hylomorphism, arguing that all natural substances are a composite of matter and form. For Man, the body is the matter, and the soul (the principle of life and activity) is the form. Neither can exist without the other; the soul is not imprisoned in the body but is the very actualization of the body's potential. This view profoundly shaped subsequent thought, positing the body not as mere inert substance but as an essential, integral component of human being.

| Philosophical Epoch | Key Figure(s) | View of Body's Matter | Implications for "Man" |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Atomism | Democritus, Lucretius | A collection of indivisible atoms | Man is a complex material aggregate, soul is also material. |

| Platonic Idealism | Plato | Imperfect, transient vessel | Body is a prison or obstacle for the immortal soul. |

| Aristotelian Hylomorphism | Aristotle | Essential component (matter) of a composite substance | Body is integral to the soul's actuality; Man is an embodied soul. |

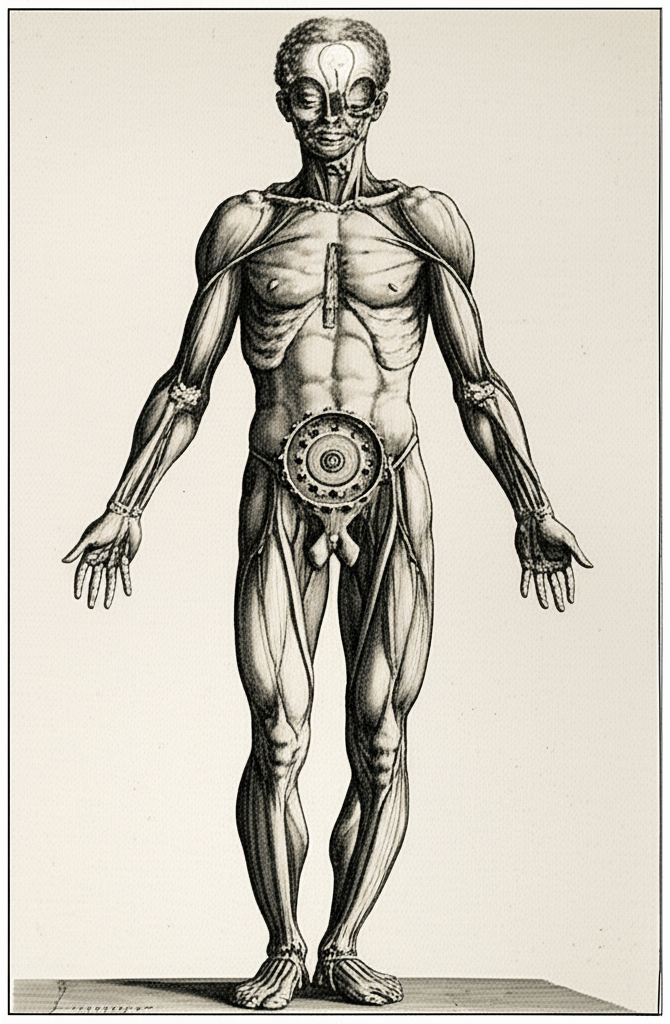

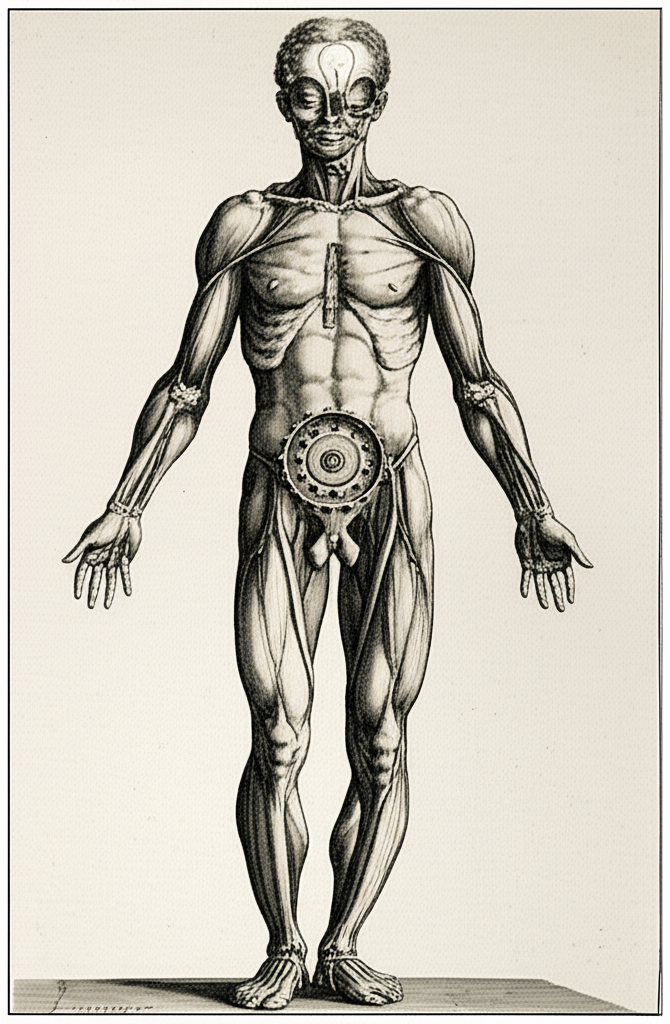

The Mechanistic Turn: Descartes and the Body as Machine

The scientific revolution, particularly the advancements in Physics by figures like Galileo and Newton, dramatically shifted the understanding of matter. The universe began to be seen as a grand, intricate machine operating according to predictable, mathematical laws. This mechanistic worldview had profound implications for the body.

René Descartes, another cornerstone of the Great Books, articulated a radical dualism that sharply separated mind and body. For Descartes, the human body was pure matter, an "extended substance" that occupied space and operated like a complex automaton. It was subject to the same physical laws as any other machine, a mere shell for the non-physical, thinking "I" – the "mind" or "soul." This perspective presented a significant challenge: how could a purely material, mechanical body interact with an immaterial mind? This "mind-body problem" became a central preoccupation of modern philosophy.

- Descartes's Dualism: The body is mere extension, a machine. Its operations, from digestion to movement, can be understood through the principles of physics. The true essence of "Man" resides in the thinking substance, the res cogitans, distinct from the res extensa.

The Body in the Age of Science: Beyond Pure Mechanism

While Descartes's dualism provided a powerful framework, the relentless progress of science, particularly in biology and neuroscience, has continued to challenge and refine our understanding of the body's matter. Modern Physics has moved beyond classical mechanics, revealing the quantum nature of reality and the intricate biochemical processes that underpin life. These discoveries often blur the lines Descartes so sharply drew.

Contemporary philosophy of mind, deeply informed by these scientific advancements, grapples with questions of emergence: Can consciousness, thought, and feeling emerge from the complex organization of purely material components? Is "Man" simply a highly sophisticated biological machine, or does the sheer complexity of our body's matter give rise to something qualitatively different?

The Philosophical Weight: What the Body's Matter Means for Man

The philosophical inquiry into the matter of the body is far from settled. It continues to shape our understanding of "Man" in several critical ways:

- Identity: Are we our bodies? If the body changes, decays, or is replaced, does our identity persist?

- Consciousness: Is consciousness a product of the brain's physical processes, or does it transcend mere matter?

- Free Will: If our body is a machine governed by physical laws, how can we claim genuine freedom of action?

- Morality: How does our understanding of the body affect our ethical responsibilities towards ourselves and others?

The journey through the Great Books of the Western World reveals a constant tension: the desire to understand the body through the lens of physics and material composition, alongside the persistent intuition that "Man" is more than just matter.

Conclusion: The Indivisible Enigma

The matter of the body remains an indivisible enigma. It is the canvas upon which our lives are painted, the instrument through which we perceive and interact with the world, and the very ground of our being. From the ancient contemplation of atoms to the sophisticated inquiries of modern neuroscience, the quest to understand this fundamental substance continues to challenge our assumptions and deepen our appreciation for the complex, multifaceted nature of "Man." The body is not merely inert matter; it is the living, breathing, feeling, and thinking nexus where the physical and the philosophical perpetually intertwine.

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Descartes mind body problem explained""

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle hylomorphism explained""