Unpacking Reality: The Enduring Wisdom of Matter and Form

A Clear Look at What Things Are Made Of and What Makes Them Them

Have you ever looked at a beautifully crafted wooden chair and wondered what, fundamentally, it is? Is it the wood itself, or the design that makes it a chair? The ancient Greeks, particularly Aristotle, grappled with this very question, giving us one of philosophy's most enduring and insightful distinctions: the matter-form distinction. Simply put, every physical object we encounter can be understood as a composite of two fundamental aspects: its matter (what it is made of, its potential) and its form (its structure, essence, or what makes it the kind of thing it is, its actuality). This idea, known as hylomorphism, is not just an ancient curiosity; it offers a powerful lens through which to understand change, identity, and the very fabric of our physical world, bridging the gap between classical Physics and profound Metaphysics.

The Building Blocks of Being: Matter and Form Defined

To truly grasp the matter-form distinction, let's break down each component. Think of it as dissecting reality into its conceptual ingredients.

What is Matter? The Potential Beneath the Surface

Matter (from the Greek hyle, meaning "wood" or "stuff") refers to the raw, undifferentiated potential out of which something is made. It's the substratum, the "stuff" that takes on various configurations.

- Potentiality: Matter, in itself, is pure potential. It doesn't have a definite shape or purpose until a form is imposed upon it.

- Indefinable: By itself, matter is difficult to define precisely because it lacks specific characteristics. It's what can become something.

- Examples:

- The bronze for a statue.

- The wood for a table.

- The clay for a pot.

- The flesh and bones for a human being.

Consider a lump of clay. In its raw state, it is simply matter. It could be a vase, a bowl, or a figurine. It has the potential for all these things, but it is none of them yet.

What is Form? The Actuality That Defines

Form (from the Greek morphe for shape, or eidos for essence) is the actualizing principle. It's the structure, arrangement, organization, and essence that makes a piece of matter into a particular kind of thing. Form gives matter its specific identity and purpose.

- Actuality: Form actualizes matter's potential, giving it specific characteristics and functions.

- Definable Essence: Form is what allows us to classify and understand objects. It's the "whatness" of a thing.

- Examples:

- The shape and design of the statue (its being a statue, not just a lump of bronze).

- The structure and purpose of the table (its being a table, not just a pile of wood).

- The design and function of the pot.

- The rational soul and organized body that defines a human being.

The form of the clay vase is what makes it a vase – its specific shape, hollow interior, and capacity to hold liquid. Without this form, it would just be clay.

The Inseparable Dance: Hylomorphism in Physical Objects

In the realm of concrete physical objects, matter and form are not separate entities floating around independently. Instead, they are inextricably linked, forming a unified whole. This union is what Aristotle called hylomorphism (from hyle + morphe). Every physical object is a composite of matter and form.

Let's illustrate with a simple table:

| Aspect | Description | Example (Table) |

|---|---|---|

| Matter | The raw stuff, potential, substratum | The wood, nails, glue |

| Form | The structure, design, essence, actuality | The specific arrangement and purpose that makes it a "table" |

| Composite | The unified physical object (Matter + Form) | The actual, functioning wooden table you sit at |

Change and Persistence

One of the most powerful insights of the matter-form distinction is how it explains change. When an object changes, it's often the form that alters while the matter persists.

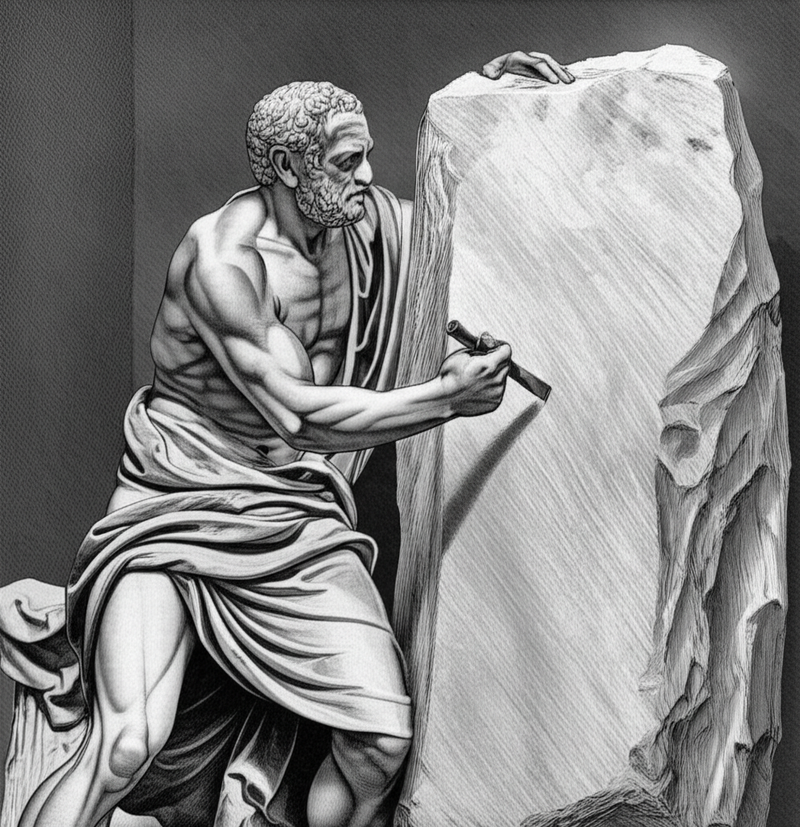

- Imagine a sculptor working with a block of marble. The marble (matter) remains, but its form changes from a rough block to a sculpted figure.

- When a tree grows, its matter (wood, leaves, sap) is constantly being replaced or augmented, but its form (the organizational principle of a tree) persists, allowing us to recognize it as the same tree over time.

This understanding of change was crucial for Aristotle's Physics, as it provided a coherent framework for observing natural processes without resorting to radical skepticism about identity.

Philosophical Resonance: From Physics to Metaphysics

The matter-form distinction isn't just a quaint ancient idea; it profoundly shapes our understanding of reality, extending its influence from the observable world to the deepest questions of existence.

Its Role in Aristotelian Physics

For Aristotle, understanding the matter-form distinction was fundamental to his Physics, which was essentially the study of nature and change. He identified four causes for everything:

- Material Cause: What something is made of (its matter).

- Formal Cause: The form, structure, or essence of a thing.

- Efficient Cause: The agent that brings something about.

- Final Cause: The purpose or end for which something exists.

The material and formal causes are directly derived from the matter-form distinction, offering a comprehensive way to analyze natural phenomena. Without understanding matter and form, our analysis of causes would be incomplete.

Its Impact on Metaphysics

Beyond explaining change, the matter-form distinction delves into profound questions of Metaphysics – the study of ultimate reality.

- Identity: What makes something the same thing over time, despite changes? The persistence of its form (or essential form) is often key.

- Substance: Aristotle considered individual physical objects (like this particular human being or this specific tree) as primary substances, composites of matter and form.

- Universals: While forms exist within individual objects, they also relate to universal concepts (e.g., the "form of treeness" that all trees share). This touches upon the debate about universals, a cornerstone of metaphysical inquiry.

The Great Books of the Western World, particularly Aristotle's Metaphysics and Physics, offer rich explorations of these concepts. In Metaphysics, Aristotle grapples with the question of "what is being?" and concludes that primary being is individual substance, understood through its matter and form. He writes, "And matter is matter of this, and form is this" (Book VII, Chapter 10), emphasizing their inseparable unity in defining an individual entity.

, while the other side reveals the emerging, defined contours of a human figure (form). The sculptor's face shows concentration, embodying the efficient cause bringing form to matter.)

, while the other side reveals the emerging, defined contours of a human figure (form). The sculptor's face shows concentration, embodying the efficient cause bringing form to matter.)

Delving Deeper: Further Exploration

The matter-form distinction is a cornerstone of classical philosophy and continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about identity, artificial intelligence, and even our understanding of biological life. If you're eager to explore this fascinating concept further, here are some suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Matter and Form Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Hylomorphism Philosophy Introduction"