The Enduring Distinction: Unpacking Matter and Form in Physical Objects

At the heart of understanding reality, particularly the physical world around us, lies a fundamental philosophical distinction: that between matter and form. This isn't merely an abstract concept; it's a potent lens through which we can analyze everything from a simple stone to a complex living organism, revealing the very principles that constitute their being. Originating prominently in ancient Greek philosophy, particularly with Aristotle, the matter-form distinction posits that every physical object is a composite of two inseparable co-principles: its underlying matter (what it is made of) and its form (what kind of thing it is, its essence, its structure). This distinction remains a cornerstone of metaphysics, influencing centuries of thought and even resonating with contemporary discussions in physics regarding the nature of reality.

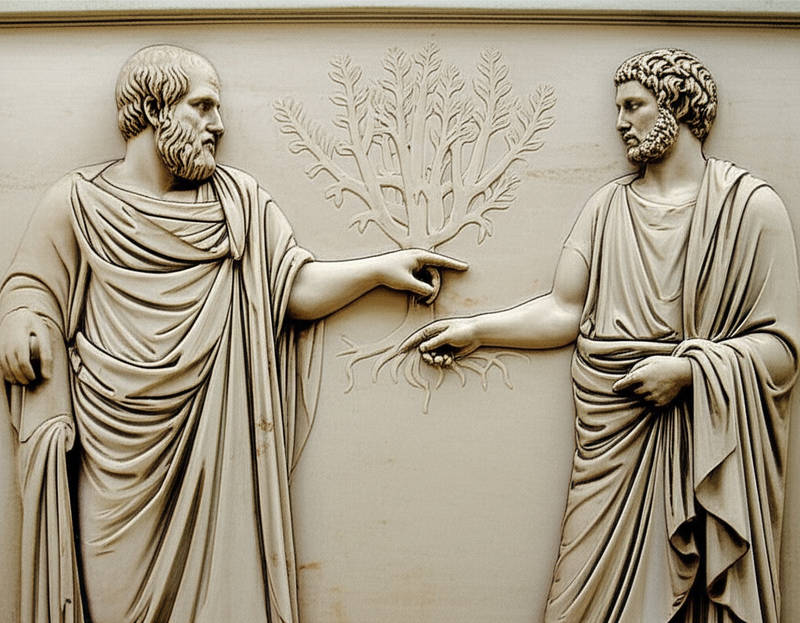

Aristotle's Enduring Legacy: The Genesis of the Distinction

The most influential articulation of the matter-form distinction, often termed hylomorphism (from Greek hyle for matter and morphe for form), comes from Aristotle, whose works like Metaphysics and Physics are cornerstones of the Great Books of the Western World. For Aristotle, substances in the world are not simply collections of properties but unified wholes, and this unity is explained by the intimate relationship between matter and form.

- Matter (Hyle): This refers to the undifferentiated substratum, the potentiality out of which something is made. It is not a specific thing itself but rather the capacity to become a specific thing. Think of it as the "stuff" without any determinate shape or function. Without form, matter is indeterminate; it is pure potentiality.

- Form (Morphe or Eidos): This is the actualizing principle, the essence, the structure, or the organization that gives matter its determinate nature. It is what makes a thing what it is. Form actualizes matter, turning potentiality into actuality. It dictates the function, properties, and boundaries of an object.

Consider a bronze statue. The bronze itself is the matter – it has the potential to be many things (a bell, a coin, a statue). The form of the statue (e.g., the specific shape of David, the pose, the artistic design) is what actualizes that bronze into being a statue.

Beyond the Abstract: Matter and Form in Physical Objects

To truly grasp this distinction, it's helpful to move beyond the purely conceptual and consider concrete examples from our everyday experience.

| Aspect | Matter (Potentiality) | Form (Actuality) |

|---|---|---|

| Example 1: A Wooden Chair | The wood (timber) – it could be a table, a beam, or firewood. | The specific design, structure, and function of a chair (seat, back, legs). |

| Example 2: A Human Being | The organic tissues, bones, blood, cells – the biological components. | The rational soul, the organizational principle that makes it a human, giving it specific capacities (thought, speech). |

| Example 3: Water (H₂O) | The hydrogen and oxygen atoms – they could form other molecules. | The specific molecular structure (two hydrogens, one oxygen) that gives water its properties. |

In each case, the matter is the raw material, the "what it's made of," while the form is the organizing principle, the "what it is." They are not separate entities that can exist independently in the world, but rather co-principles that are conceptually distinct yet exist together in every physical object. You cannot have a chair without wood (or some other material), nor can you have wood qua chair without the form of a chair.

The Inseparable Yet Distinct Interplay

A crucial insight from Aristotle is that matter and form are not two things glued together, but rather two aspects of a single reality. They are co-principles, meaning they require each other to constitute a complete physical substance. Form gives matter definition and purpose, actualizing its potential. Matter provides the substrate for form to inhere.

This dynamic relationship is key to understanding change. When an object undergoes change (e.g., a tree becoming a table), its matter persists, but its form changes. The wood remains, but its form as a tree is replaced by its form as a table. This framework offers a profound way to understand identity, persistence, and transformation in the physical world.

From Ancient Greece to Modern Thought: Metaphysics and Physics Converge

The matter-form distinction, born in ancient Greek metaphysics, continues to resonate through the centuries. In the medieval period, thinkers like Thomas Aquinas extensively developed Aristotelian hylomorphism, applying it to theological and philosophical questions about human nature, angels, and God.

Even in modern science, though the terminology has shifted, the underlying conceptual challenge of understanding constituents and organization persists. While contemporary physics doesn't speak of "matter" and "form" in the same Aristotelian sense, it grapples with analogous questions:

- What are the fundamental particles (the "matter")?

- How do these particles organize into atoms, molecules, and larger structures (the "form")?

- What gives a particular arrangement of particles its specific properties and identity?

From the quarks and leptons that make up protons and neutrons, to the complex molecular structures that define life, the interplay between fundamental components and their specific organization continues to be a central inquiry. The enduring legacy of the matter-form distinction lies in its capacity to provide a robust framework for contemplating the very nature of existence.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Matter and Form Explained"

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Hylomorphism Philosophy"