The Unfolding Cosmos: A Philosophical Journey Through the Mathematics of Space and Geometry

From the ancient Greek philosophers who saw divine patterns in geometric forms to modern physicists grappling with the curvature of spacetime, the relationship between mathematics, space, and geometry has been a cornerstone of human inquiry. This pillar page delves into the profound philosophical questions that arise when we apply the rigorous language of quantity to the vast expanse of space, exploring how our understanding of form has evolved and continues to shape our perception of reality. We will embark on a journey through history, examining how thinkers have used mathematical tools to describe, understand, and even redefine the very fabric of existence, revealing that geometry is not merely a tool for measurement, but a lens through which we comprehend the cosmos.

The Ancient Blueprint: Geometry as the Language of Reality

For millennia, the study of geometry was considered the highest intellectual pursuit, a direct pathway to understanding the fundamental forms of the universe. The ancients believed that mathematics, particularly geometry, provided insights into an unchanging, perfect reality that underpinned the transient world of appearances.

Plato's Ideal Forms and the Geometric Cosmos

Plato, a towering figure in Western philosophy, famously inscribed above the entrance to his Academy: "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here." For Plato, geometric forms were not mere abstractions but perfect, eternal Forms existing in a realm beyond our senses. In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato articulates a cosmology where the Demiurge fashions the universe from primordial chaos using geometric principles, specifically the five Platonic solids (tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, cube, dodecahedron) to construct the elements and the cosmos itself. This vision posits that the universe is fundamentally ordered by mathematical principles, where space is structured according to ideal forms.

Euclid's Elements: The Axiomatic Foundation of Space

Roughly a century after Plato, Euclid of Alexandria codified the understanding of geometry in his monumental work, The Elements. This treatise laid down a rigorous axiomatic system, starting with basic definitions, postulates, and common notions, and proceeding to deduce a vast array of theorems about points, lines, planes, and solids.

Key Contributions of Euclid's Elements:

- Axiomatic Method: Demonstrated how complex truths could be derived logically from a few self-evident statements.

- Definition of Space: Provided a clear, consistent framework for understanding three-dimensional space through geometric constructs.

- The Fifth Postulate: Its apparent lack of self-evidence would later become a pivotal point for the development of non-Euclidean geometries, challenging the very nature of space.

Euclid's work was more than a geometry textbook; it was a philosophical statement about the rational order of the universe and the power of human reason to apprehend it. The clarity and certainty of Euclidean geometry deeply influenced Western thought, setting the standard for scientific and philosophical inquiry for over two millennia.

Navigating the Void: Concepts of Space from Aristotle to Newton

As philosophical thought evolved, so too did the conceptualization of space. Is space an empty container, a relational construct, or an inherent property of matter? These questions have profoundly shaped our understanding of quantity and its relation to physical reality.

Aristotle's Place and the Rejection of Void

Aristotle, while admiring the mathematics of geometry, held a different view of space. He rejected the notion of an infinite void, arguing instead for a concept of "place" (topos) as the inner boundary of the containing body. For Aristotle, space was not an independent entity but intrinsically linked to the objects within it. The idea of quantity was applied to the extension of bodies, not to an empty space itself. This geocentric, plenum universe contrasted sharply with later, more abstract mathematical conceptions of space.

The Cartesian Revolution: Unifying Algebra and Geometry

René Descartes, in the 17th century, revolutionized the way we represent space with his invention of coordinate geometry. By assigning numerical coordinates to points, Descartes effectively merged algebra with geometry, allowing geometric forms to be described by equations and algebraic problems to be visualized geometrically.

Impact of Cartesian Geometry:

- Quantification of Space: Made space amenable to precise numerical analysis, directly applying the concept of quantity to its properties.

- Analytic Geometry: Provided a powerful new tool for understanding and manipulating forms in space.

- Philosophical Implications: Reinforced the idea that the physical world could be fully understood through mathematics and mechanical principles.

Absolute vs. Relational Space: Newton and Leibniz

The 17th century also saw a profound debate about the nature of space itself, primarily between Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

| Concept of Space | Proponent | Description | Philosophical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Space | Isaac Newton | An infinite, immovable, and eternal container existing independently of matter. It is the stage upon which physical events unfold. | Suggests a divine, omnipresent being; provides a fixed reference frame for motion; an empty quantity. |

| Relational Space | G.W. Leibniz | Space is merely the collection of spatial relations (distances, directions) between objects. It does not exist independently of the objects within it. | Emphasizes the interconnectedness of existence; avoids the problem of "empty" space; quantity arises from relations. |

This debate, deeply rooted in philosophical and theological considerations, highlighted the ongoing tension between a purely mathematical abstraction of space and its empirical reality.

Beyond the Straight Line: The Unfolding of Form in Non-Euclidean Geometries

The Enlightenment and subsequent scientific revolutions brought about an unprecedented expansion of mathematical thought, leading to radical new understandings of space and form. The once unshakeable foundations of Euclidean geometry began to tremble.

Challenging the Fifth Postulate

For centuries, mathematicians struggled with Euclid's Fifth Postulate (the parallel postulate), which states that through a point not on a given line, there is exactly one line parallel to the given line. Attempts to prove it from the other axioms failed, leading to the groundbreaking realization in the 19th century that consistent geometries could exist where this postulate was not true.

The Birth of Non-Euclidean Geometries

Mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss, János Bolyai, and Nikolai Lobachevsky independently developed geometries where the Fifth Postulate was denied.

- Hyperbolic Geometry: Through a point not on a given line, there are multiple lines parallel to the given line. This geometry can be visualized on a saddle-shaped surface, where triangles' angles sum to less than 180 degrees.

- Elliptic Geometry (Riemannian Geometry): Through a point not on a given line, there are no lines parallel to the given line. This geometry can be visualized on the surface of a sphere, where lines (great circles) always intersect, and triangles' angles sum to more than 180 degrees.

These discoveries were not just mathematical curiosities; they fundamentally altered the philosophical understanding of space and form. No longer was Euclidean geometry the only true description of physical space. The choice of geometry became an empirical question, dependent on the actual curvature of the universe.

Einstein's Spacetime: Geometry as Gravity

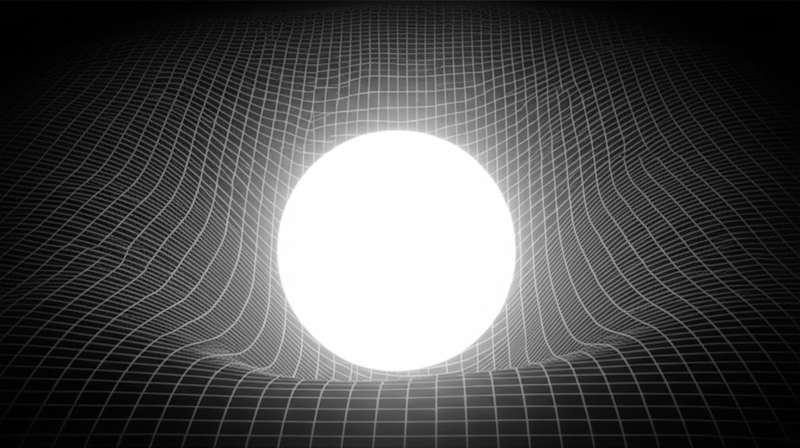

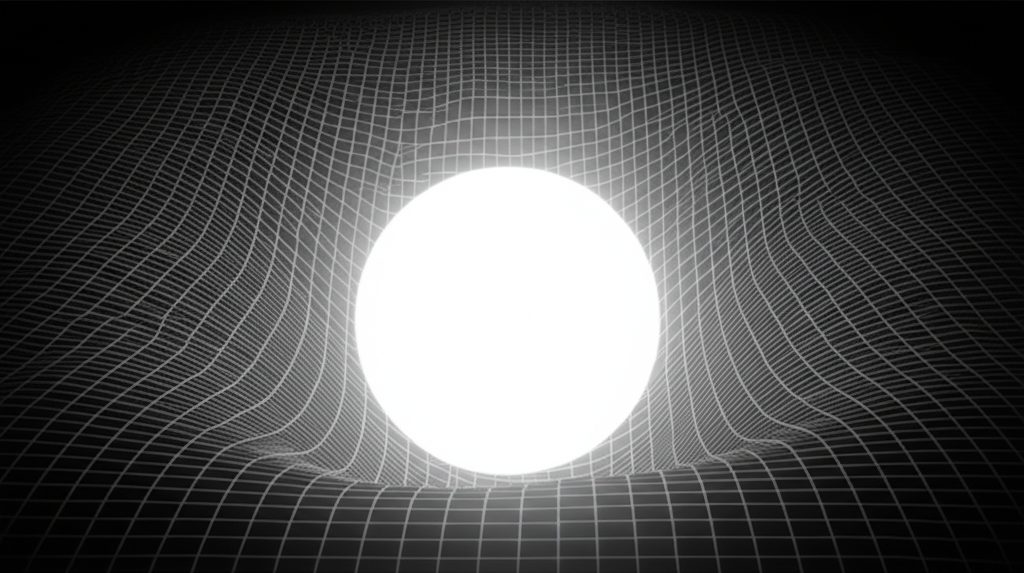

The philosophical implications of non-Euclidean geometries reached their zenith with Albert Einstein's theories of relativity. In his General Theory of Relativity, Einstein proposed that gravity is not a force but a manifestation of the curvature of spacetime itself, caused by the presence of mass and energy.

causing a noticeable curvature or "dimple" in the grid, symbolizing how gravity warps the fabric of space and time according. Smaller objects or light rays are shown following the curved paths created by this distortion, illustrating the concept of gravitational lensing.)

causing a noticeable curvature or "dimple" in the grid, symbolizing how gravity warps the fabric of space and time according. Smaller objects or light rays are shown following the curved paths created by this distortion, illustrating the concept of gravitational lensing.)

This meant that the geometry of the universe is dynamic and influenced by its contents. Our universe is not a static, flat Euclidean stage, but a four-dimensional manifold whose form is constantly being shaped by matter and energy. Here, mathematics provides the precise language to describe this intricate dance of quantity, space, and form.

Quantity and Quality: The Philosophical Interplay

The journey from abstract mathematical principles to concrete physical reality highlights a continuous philosophical tension: how do quantitative descriptions of space relate to our qualitative experience of it?

The Infinite and the Infinitesimal

The concepts of the infinite and the infinitesimal have plagued philosophers and mathematicians for centuries. From Zeno's paradoxes challenging motion to the development of calculus, mathematics has provided tools to grapple with these extreme quantities, but not without raising deep philosophical questions about the nature of continuity, discreteness, and the limits of human understanding. Does space truly extend infinitely, or is it bounded in ways our current mathematics cannot yet fully describe?

The Abstract and the Real

Mathematics often deals with perfect, abstract forms—ideal circles, perfectly straight lines, dimensionless points. Yet, the physical world is messy and imperfect. The philosophical challenge lies in understanding how these ideal mathematical constructs can so accurately describe, predict, and even define the space we inhabit. Is mathematics discovered, inherent in the structure of the cosmos, or is it invented, a powerful tool of the human mind imposed upon reality? This question, echoing Plato's Forms, remains central to the philosophy of mathematics and space.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Form and Space

The history of mathematics, space, and geometry is a testament to humanity's enduring quest to understand the forms that govern our existence. From the foundational axioms of Euclid to the curved spacetime of Einstein, mathematics has provided the indispensable language to articulate our deepest insights into the nature of reality. It reveals that space is not merely an empty backdrop, but a dynamic, mathematically describable entity whose form and quantity are intimately intertwined with the very fabric of the cosmos. As we continue to probe the mysteries of the universe, from quantum foam to cosmic horizons, the mathematics of space and geometry will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of our philosophical and scientific endeavors, continually challenging and expanding our understanding of what it means to exist within a structured, quantifiable reality.

**## 📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Philosophy of Space and Time | General Relativity Explained"**

**## 📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Non-Euclidean Geometry Explained Simply"**