The Unseen Architecture: A Philosophical Journey Through the Mathematics of Space and Geometry

From the ancient Greek contemplation of ideal forms to the modern physicist's exploration of a curving cosmos, mathematics has always been the language through which humanity attempts to comprehend the fundamental nature of space and geometry. This pillar page delves into the profound philosophical questions that arise when we apply rigorous thought to the quantity and form of our existence, tracing a lineage of inquiry that spans millennia and continues to shape our understanding of reality itself. We will explore how thinkers, from Euclid to Kant and beyond, have wrestled with the implications of mathematical truths for the structure of the universe and our perception of it.

The Immutable Blueprint: Geometry's Ancient Roots

The journey into the mathematics of space begins, for many, with the foundational work of ancient Greece. Here, geometry was not merely a practical tool for surveying land, but a profound philosophical discipline, revealing universal truths about form and quantity.

Euclid's Elements and the Ideal Forms

Euclid's Elements, a cornerstone of the Great Books of the Western World, stands as a monumental achievement, establishing a deductive system for understanding geometric form. Through axioms, postulates, and theorems, Euclid meticulously built a universe of points, lines, and planes, demonstrating how complex shapes could be derived from simple, self-evident truths.

- Axiomatic Foundations: Euclid's work showed that the entire edifice of geometry could be constructed from a few basic assumptions, prompting philosophical reflection on the nature of truth and certainty.

- Ideal Forms: For Plato, geometry was a pathway to understanding the eternal and unchanging Forms that lie beyond the sensible world. The perfect circle or triangle, though never perfectly realized in physical space, represented an ideal form accessible through pure thought and mathematics. The study of geometry was, therefore, a purification of the soul, turning the mind towards true being.

- Quantity and Measure: The geometric figures themselves, from the Pythagorean theorem's relationship between the sides of a right triangle to the calculation of volumes, are inherently about quantity. They provide a precise language for measuring and comparing the spatial attributes of objects.

The Cartesian Grid: Unifying Number and Form

The philosophical landscape of space and geometry underwent a radical transformation with René Descartes in the 17th century. His innovation of analytical geometry, detailed in his Geometry, bridged the ancient divide between arithmetic and geometry, offering a new way to conceptualize quantity and form.

Descartes and the Coordinate System

Descartes' genius lay in translating geometric figures into algebraic equations and vice versa. By establishing a coordinate system, he made it possible to describe any point in space using numbers, thus making the continuous quantity of space amenable to the discrete quantity of arithmetic.

- Algebraic Forms: A circle could now be represented not just as an ideal form, but as an equation (e.g., x² + y² = r²), allowing for precise manipulation and analysis.

- Quantifying Space: This synthesis provided a powerful new tool for understanding the quantity and relationships within space, enabling a more rigorous and systematic approach to scientific inquiry. It fundamentally altered the way philosophers and scientists conceived of the universe, moving towards a more mechanistic and quantifiable understanding.

Kant's Revolution: Space as a Condition of Experience

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, offered a profound and enduring philosophical perspective on space, arguing that it is not merely an external container but an inherent structure of the human mind.

Space as an A Priori Intuition

For Kant, space is an "a priori intuition," meaning it is a necessary condition for our experience of the world, rather than something we derive from experience. We cannot conceive of objects existing outside of space.

- The Synthetic A Priori: Kant argued that geometric propositions (e.g., "a straight line is the shortest distance between two points") are "synthetic a priori" truths. They are not merely definitional (analytic), nor are they derived from observation (a posteriori). Instead, they are universally true because space itself, as we perceive it, is structured in a Euclidean manner by our minds.

- Mathematics and Understanding: The certainty of mathematics, particularly geometry, thus reflects the fundamental structure of our cognitive faculties. Our ability to apply mathematics to the world and derive certain knowledge is explained by the fact that the world, as we experience it, is already organized by these innate spatial intuitions.

- Quantity and Form in Perception: Our perception of quantity (how much of something there is) and form (the shape it takes) is inextricably linked to this a priori spatial framework.

Beyond Euclid: The Expanding Universe of Geometry

The 19th century witnessed a seismic shift in our understanding of space with the development of non-Euclidean geometries. This intellectual revolution profoundly challenged Kant's view and paved the way for modern physics.

Challenging the Fifth Postulate

Mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss, Nikolai Lobachevsky, and Bernhard Riemann explored the consequences of rejecting Euclid's fifth postulate (the parallel postulate). Their work revealed that consistent and logical geometries could exist where:

- Hyperbolic Geometry: Through a point not on a given line, infinitely many lines can be drawn parallel to the given line (e.g., the surface of a saddle).

- Elliptic Geometry: Through a point not on a given line, no lines can be drawn parallel to the given line (e.g., the surface of a sphere, where "lines" are great circles).

Implications for Space and Reality

The existence of multiple consistent geometries opened up a profound philosophical question: Which geometry describes the actual space of our universe?

- Empirical Space: This question transformed space from a purely conceptual or a priori entity into something that could be empirically investigated. The form of space became a matter of physical observation, not just philosophical deduction.

- Relativity and Curved Space-Time: Albert Einstein's theories of relativity, building on Riemann's work, demonstrated that space (and time) is not a fixed, absolute background, but a dynamic entity that can be curved by mass and energy. The mathematics of non-Euclidean geometry became essential for describing the actual form and quantity of the cosmos, where gravity is understood as the curvature of space-time.

Philosophical Reverberations: Quantity, Form, and the Fabric of Existence

The journey through the mathematics of space and geometry reveals a continuous philosophical dialogue about the nature of reality.

Key Philosophical Questions:

- The Nature of Mathematical Objects: Do geometric forms and quantities exist independently of the human mind (Platonism), or are they mental constructs (Formalism, Intuitionism)?

- The Relationship Between Mathematics and Reality: Why is mathematics so effective at describing the physical world? Is the universe inherently mathematical, or do we impose a mathematical structure upon it?

- The Structure of Space: Is space an absolute container, a relational property of objects, or a subjective intuition? What does it mean for space to be curved, finite, or infinite?

| Era/Thinker | Key Contribution | Concept of Space | Role of Mathematics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Greeks (Euclid, Plato) | Axiomatic Geometry, Ideal Forms | Objective, Ideal, Fixed | Reveals eternal truths, aids contemplation of Forms |

| Descartes | Analytical Geometry | Quantifiable, Measurable | Unifies number and form, instrumental for science |

| Kant | Space as A Priori Intuition | Subjective, Innate | Structures experience, provides certainty for geometry |

| Non-Euclidean Geometers | Alternative Geometries | Potentially Curved, Empirical | Describes diverse spatial forms, testable by physics |

The profound dance between mathematics, space, quantity, and form continues to unravel the cosmic tapestry. It invites us to ponder not just what the universe is made of, but how it is shaped, how we perceive it, and what our capacity for abstract thought truly means for our place within its grand design.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""The Geometry of the Universe - Neil deGrasse Tyson""

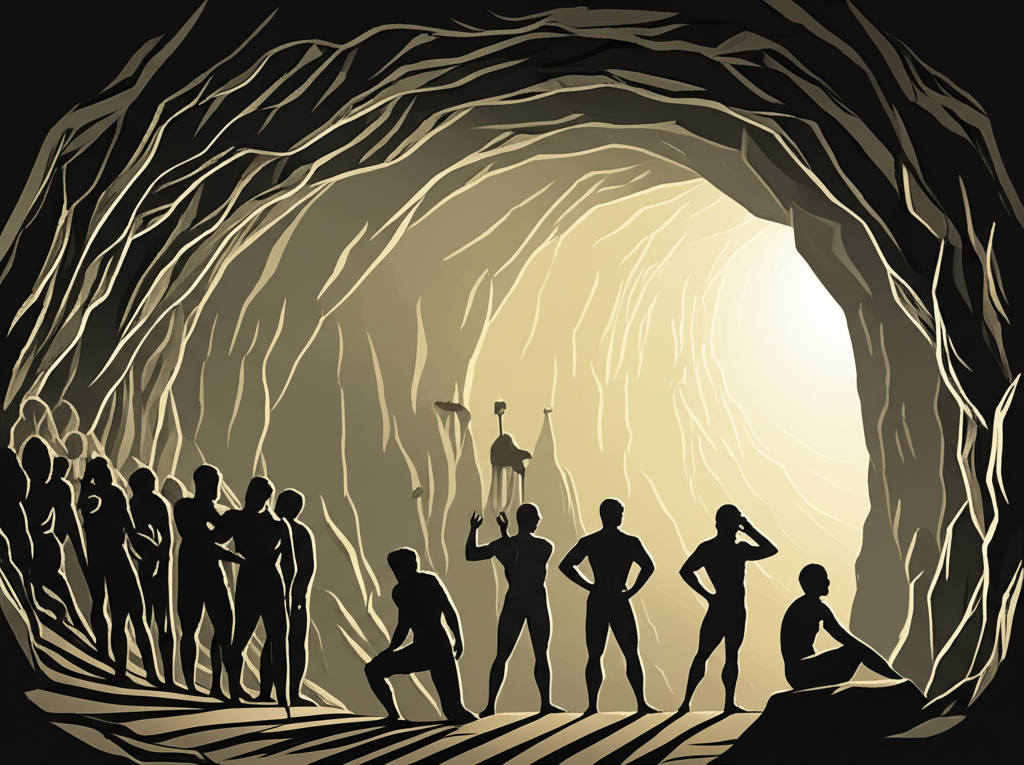

2. ## 📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Philosophy of Mathematics: Plato, Aristotle, and the Nature of Numbers""