The Logical Structure of Scientific Hypotheses: A Philosophical Inquiry

The heart of scientific progress beats with the formulation and testing of hypotheses. But what gives these educated guesses their power? It's not merely their empirical content, but the robust logical structure that underpins them. This article delves into how logic provides the essential framework for scientific reasoning, transforming observations into testable propositions and ultimately, into knowledge. We'll explore the philosophical underpinnings that allow a hypothesis to bridge the gap between the known and the unknown, guiding our quest for understanding within the realm of science.

The Unseen Architecture of Scientific Inquiry

From the ancient Greek philosophers, whose reasoning laid the groundwork for formal logic, to the modern scientific method, the journey of understanding has always been a dance between observation and interpretation. At the core of this dance lies the hypothesis – a proposed explanation for a phenomenon, a provisional statement awaiting the rigorous scrutiny of evidence. Yet, a hypothesis is far more than a mere guess; it is a carefully constructed proposition, imbued with a specific logical structure that dictates how it can be tested, evaluated, and potentially, contribute to our body of scientific knowledge.

When we speak of logic in science, we're not just talking about common sense. We're referring to the formal principles of valid inference, the rules that govern how we move from premises to conclusions. It's this formal reasoning that transforms the chaotic influx of empirical data into coherent, testable ideas.

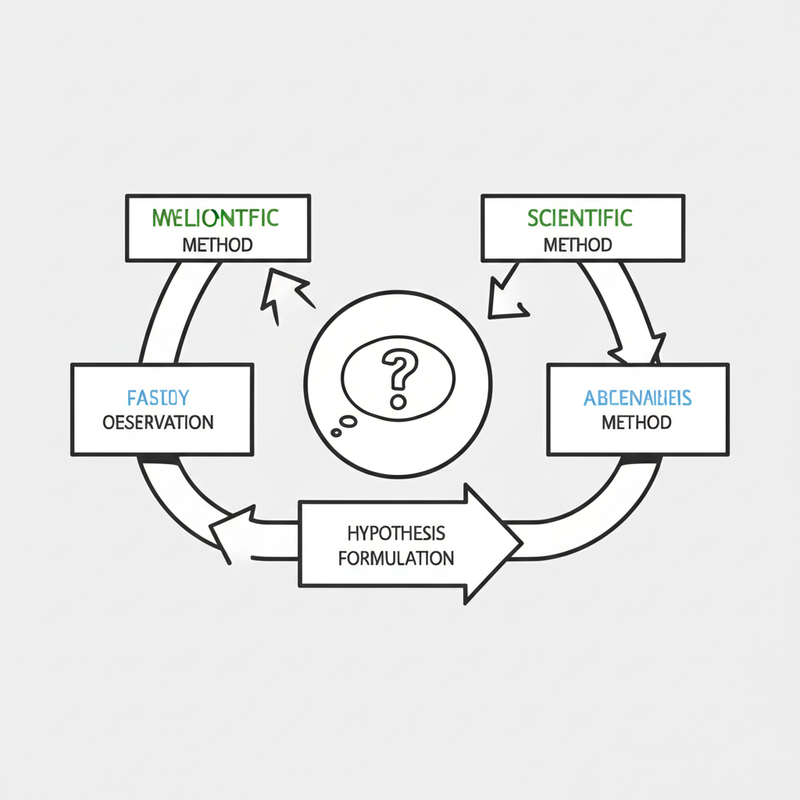

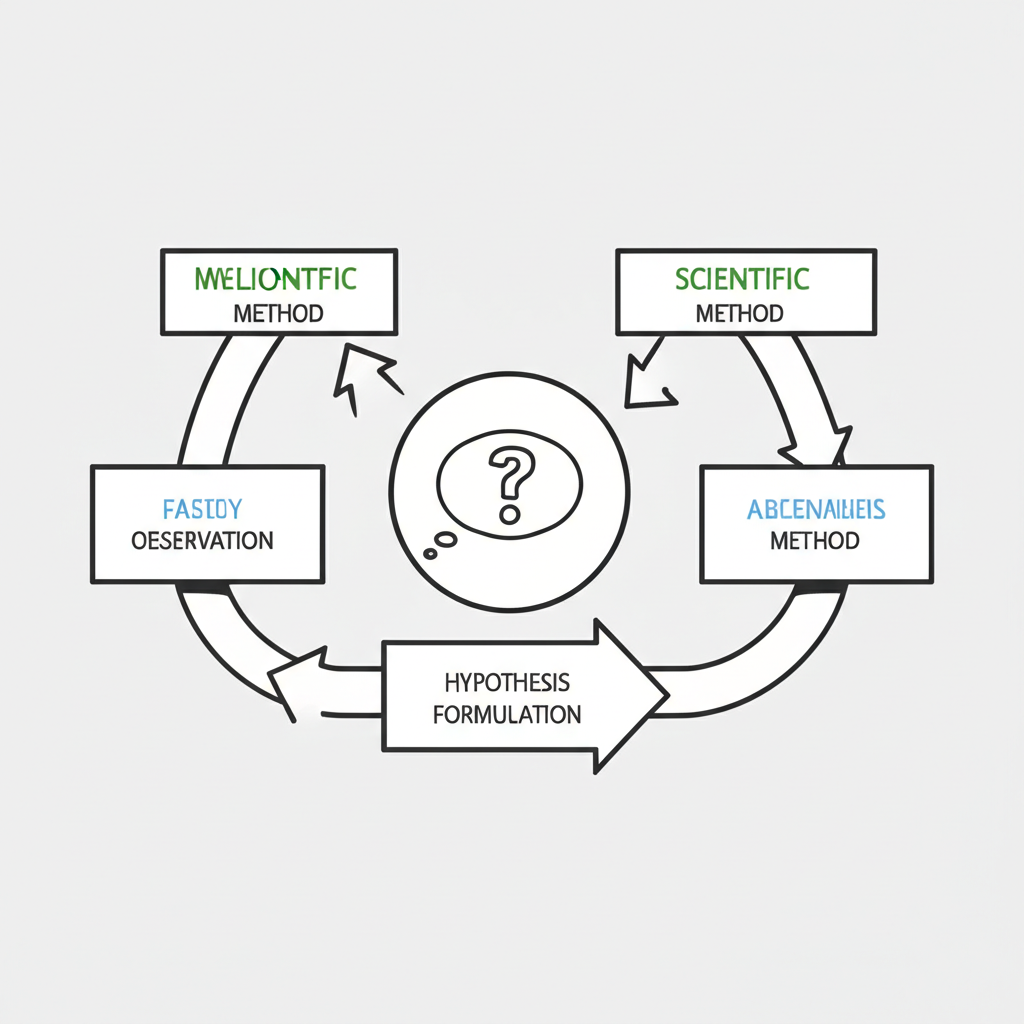

From Observation to Proposition: The Birth of a Hypothesis

How does a hypothesis come into being? Often, it begins with an observation that piques our curiosity, a pattern that demands an explanation. This initial step frequently involves inductive reasoning, a process famously scrutinized by thinkers like David Hume, where we move from specific instances to general principles.

Consider the following stages in the formation of a hypothesis:

- Observation: Noticing a recurring event or phenomenon. (e.g., Every time I drop an apple, it falls to the ground.)

- Pattern Recognition: Identifying regularities or correlations. (e.g., All unsupported objects near the Earth's surface fall downwards.)

- Inductive Leap: Generalizing from these specific observations to a broader principle. This is where the hypothesis begins to take shape. (e.g., Perhaps there's an invisible force pulling objects towards the Earth.)

- Formulation: Articulating the general principle as a testable statement. (e.g., If a mass exists, then it exerts a gravitational force on other masses, proportional to their product and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.)

This inductive leap, while crucial, is inherently probabilistic; it doesn't guarantee the truth of the conclusion. As illuminated in many philosophical texts, including those within the Great Books of the Western World, the problem of induction reminds us that past regularities do not guarantee future ones. This is precisely why the logical structure of a hypothesis must allow for rigorous testing, moving beyond mere probability.

The Formal Face of a Hypothesis

A well-formed scientific hypothesis isn't just any statement; it adheres to certain logical and practical criteria that make it amenable to scientific investigation.

- Testability: The hypothesis must generate predictions that can be empirically observed or measured.

- Falsifiability: As Karl Popper famously argued, a true scientific hypothesis must be capable of being proven wrong. If there's no conceivable observation that could falsify it, it falls outside the realm of science.

- Clarity and Precision: The terms and relationships within the hypothesis must be unambiguous.

- Parsimony (Ockham's Razor): Among competing hypotheses, the simplest one that explains the phenomena is often preferred.

Most hypotheses take the form of an "if...then..." statement, which is a classic conditional statement in logic. For example: "If plants are exposed to red light, then their growth rate will increase compared to plants exposed to blue light." This structure is not accidental; it's a logical blueprint for deriving testable predictions.

Testing the Waters: Deductive Consequences and Empirical Scrutiny

Once a hypothesis is formulated, the process shifts to deductive reasoning. From our general hypothesis, we deduce specific, observable predictions. If the hypothesis (H) is true, then a particular observation (O) should follow under specific conditions.

- Hypothesis (H): All swans are white.

- Deductive Prediction: If I observe a swan, it will be white.

We then design experiments or make observations to see if these predictions hold true. This is where science meets the world.

, then branching to "Deductive Predictions" (represented as specific "if-then" statements), leading to "Experimentation/Observation" (depicting lab equipment or a telescope), and finally looping back to "Analysis & Conclusion" with options for "Support Hypothesis" or "Revise Hypothesis," all against a backdrop of classical philosophical texts.)

, then branching to "Deductive Predictions" (represented as specific "if-then" statements), leading to "Experimentation/Observation" (depicting lab equipment or a telescope), and finally looping back to "Analysis & Conclusion" with options for "Support Hypothesis" or "Revise Hypothesis," all against a backdrop of classical philosophical texts.)

The outcome of these empirical tests leads us to either support the hypothesis or, crucially, to reject or revise it. This iterative process of reasoning, testing, and refining is the engine of scientific progress.

The Verdict: Verification, Falsification, and the Limits of Logic

When our observations match our predictions, it provides support for our hypothesis. However, a critical point in the logic of science is that no amount of confirming evidence can prove a universal hypothesis absolutely true. This is the problem of induction again – seeing a million white swans doesn't logically guarantee that the next swan won't be black.

This led philosophers like Karl Popper to emphasize falsification. Rather than seeking to verify a hypothesis, science should aim to falsify it. A single black swan is enough to falsify the hypothesis that "all swans are white." This approach highlights the provisional nature of scientific knowledge and emphasizes that science progresses by eliminating incorrect theories.

| Aspect | Verification (Inductive) | Falsification (Deductive) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | To confirm or support a hypothesis by accumulating positive evidence. | To disconfirm or refute a hypothesis by finding contradictory evidence. |

| Logical Basis | Inductive reasoning; moves from specific observations to general conclusions. | Deductive reasoning; if a prediction derived from a hypothesis is false, then the hypothesis itself must be false (Modus Tollens). |

| Strength | Builds confidence in a hypothesis through repeated success. | Offers a clear criterion for distinguishing science from non-science; allows for definitive rejection. |

| Weakness | Cannot definitively prove a universal hypothesis true; susceptible to the problem of induction. | May discard potentially useful hypotheses too quickly; science often progresses through gradual accumulation of evidence, not just refutation. |

The ongoing debate between verification and falsification underscores the complex interplay of logic and pragmatism in scientific reasoning. While pure logic might favor falsification's definitive power, the reality of science often involves a more nuanced accumulation of evidence.

Beyond Simple Logic: The Role of Context and Theory

It's also important to remember that hypotheses don't exist in a vacuum. They are always embedded within broader theoretical frameworks and paradigms, as explored by thinkers like Thomas Kuhn. These larger theories influence what questions are asked, what observations are deemed relevant, and how data is interpreted. The logical structure of a hypothesis is thus not just an isolated "if...then" statement, but a part of a larger, interconnected web of scientific reasoning.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Understanding

The logical structure of scientific hypotheses is the invisible scaffolding upon which our understanding of the natural world is built. From the inductive leap that sparks a new idea to the rigorous deductive testing that puts it to the empirical test, logic provides the essential tools for scientific reasoning. While no hypothesis can ever be definitively proven true in an absolute sense, the continuous cycle of formulation, prediction, and testing, guided by sound logic, allows science to progressively refine our knowledge, pushing the boundaries of what we understand and opening new avenues for inquiry. It's a testament to the enduring power of reasoning in our collective human quest for truth.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Karl Popper Falsification Philosophy of Science"

2. ## 📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Explained"