The Indispensable Dance: Exploring the Logic of Same and Other in Metaphysics

The very fabric of reality, as we attempt to grasp it, hinges on a seemingly simple distinction: what is the same and what is other? This isn't merely a linguistic quirk but a profound logic that underpins all Metaphysics, dictating how we conceive of Being itself. From ancient Greek philosophers grappling with change to modern inquiries into identity, the interplay of Same and Other has remained a foundational challenge, shaping our understanding of existence, knowledge, and the very structure of thought. This article will delve into the historical development and enduring significance of this fundamental dichotomy, revealing its critical role in shaping Western philosophy.

The Primacy of Distinction: Why Same and Other Matter

At its core, Metaphysics seeks to understand the fundamental nature of reality. But how can we speak of reality without first distinguishing one thing from another? How can we identify a Being without also understanding what it is not? The concepts of Same and Other are not just descriptive tools; they are the very scaffolding upon which our conceptual world is built. Without them, we are left with an undifferentiated, incomprehensible flux, incapable of discerning identity, change, or relation.

Consider the simple act of recognizing a chair. We identify it as the same chair we saw yesterday, distinct from other objects like a table or a lamp. This seemingly trivial act engages a complex metaphysical and logical operation. Is it the same chair if a leg is replaced? Where does sameness end and otherness begin? These are not just semantic games; they are the bedrock questions that compel philosophical inquiry.

Ancient Echoes: Parmenides, Plato, and the Genesis of the Problem

The philosophical journey into Same and Other begins in earnest with the Presocratics, particularly Parmenides.

Parmenides: The Unyielding Monism of Being

Parmenides, a figure of immense influence, famously argued that Being is, and Not-Being is not. For him, Being is:

- One: Indivisible and without parts.

- Eternal: Without beginning or end.

- Unchanging: Incapable of becoming or perishing.

- Homogeneous: All of the same kind.

This radical monism presented a profound challenge: if only Being exists, and Being is utterly uniform and singular, how can there be multiplicity, difference, or change? How can one Being be other than another if there is only one Being? Parmenides' logic, though seemingly irrefutable on its own terms, rendered the world of appearances—with its inherent differences and transformations—an illusion. He pushed the concept of Same to its absolute extreme, effectively annihilating the possibility of Other.

Plato's Sophist: Reconciling Difference with Being

Plato, deeply influenced by Parmenides but unwilling to abandon the reality of change and multiplicity, directly confronted this challenge in his dialogue The Sophist. Through the voice of the Eleatic Stranger, Plato introduces a revolutionary idea: Difference (or Otherness) is itself a fundamental Form, a genus of Being.

Plato's solution can be summarized as follows:

- Things participate in Forms: A particular object is what it is by participating in the Form of its essence.

- Forms interweave: Forms do not exist in isolation but relate to one another.

- The Great Kinds: Plato identifies five primary Forms (or "Great Kinds") that interweave:

- Being: That which exists.

- Same: That by which a thing is identical to itself.

- Other: That by which a thing is distinct from other things.

- Rest: That by which a thing remains stable.

- Motion: That by which a thing changes.

By positing Otherness as a fundamental aspect of Being, Plato could logically explain how something is (itself, by participation in Same) and is not (other things, by participation in Other). This ingenious move allowed for the existence of multiple, distinct entities and the reality of change without violating Parmenides' insistence that Not-Being cannot be. Instead, "is not" simply means "is other than," not "does not exist."

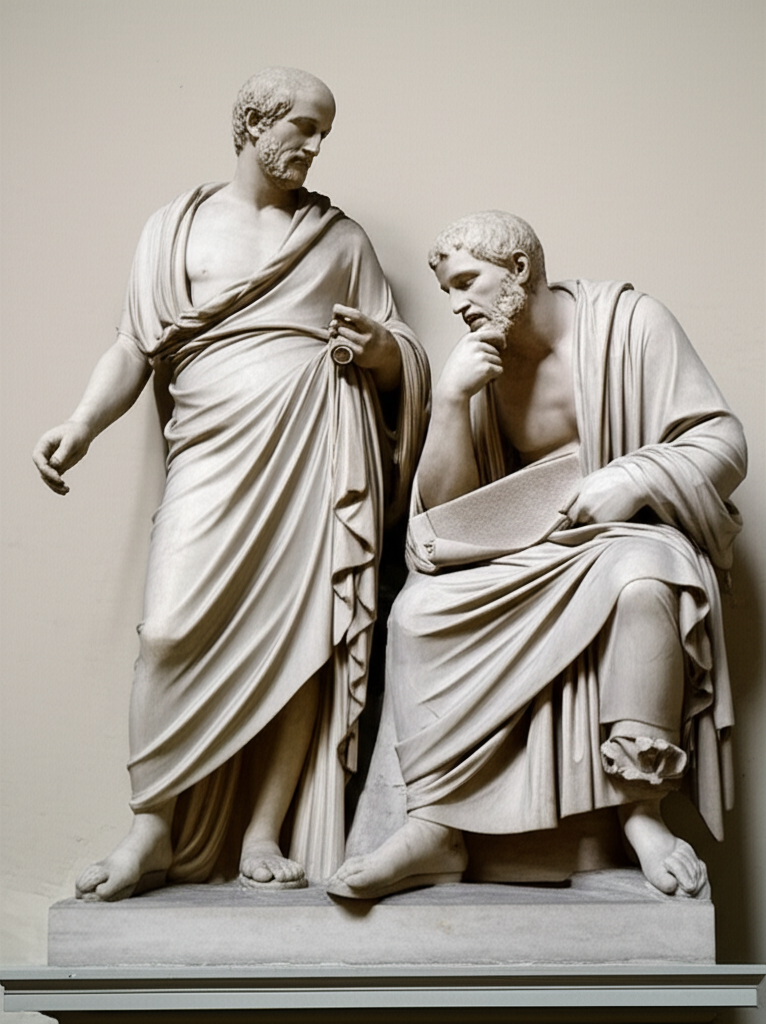

Aristotle's System: Substance, Essence, and Identity

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, further refined the logic of Same and Other within his comprehensive metaphysical system. While he rejected Plato's separate Forms, Aristotle's focus on individual substances and their essences provided a robust framework for understanding identity and distinction.

For Aristotle:

- Substance (Ousia): The primary category of Being, that which exists in itself and is the subject of predicates. A substance is fundamentally itself (Same).

- Essence: What a thing is, its defining characteristics. The essence of a human is rationality; this is what makes a human the same as other humans of that species.

- Accidents: Properties that can change without altering the fundamental identity of the substance (e.g., color, size).

- Principle of Non-Contradiction: A cornerstone of Aristotle's logic, stating that a thing cannot both be and not be the same thing at the same time and in the same respect. This principle directly underpins our ability to distinguish Same from Other. If A is A, then A cannot simultaneously be Not-A.

Aristotle's categories and logical principles provided the tools to analyze how things are identical to themselves (Same) and different from others (Other) based on their essential nature and accidental properties.

Hegel's Dialectic: Difference Within Identity

Moving forward to the modern era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel introduced a radically dynamic understanding of Same and Other, particularly in his Phenomenology of Spirit and Science of Logic. For Hegel, identity (Same) is not a static, self-contained concept but inherently contains and is defined by difference (Other).

Hegel's key insights include:

- Identity as a process: True identity is not merely sameness, but identity that has gone through difference and returned to itself. It is a mediated identity.

- The Dialectical Method: Reality and thought progress through a three-stage process:

- Thesis: A concept (e.g., Being, which is initially undifferentiated and abstract).

- Antithesis: The negation or Other of the thesis (e.g., Not-Being).

- Synthesis: A higher unity that sublates (preserves, negates, and elevates) both thesis and antithesis (e.g., Becoming, which is the truth of both Being and Not-Being).

- The Unity of Opposites: For Hegel, concepts like Same and Other, Being and Not-Being, are not merely external to each other but are internally related and necessary for each other's full comprehension. The Same is only understood in contrast to the Other; the Other defines the boundaries of the Same.

This complex interplay means that difference is not an external threat to identity but an internal, driving force of development and self-realization, both in thought and in the Absolute Spirit.

The Enduring Relevance in Contemporary Metaphysics

The logic of Same and Other continues to permeate contemporary philosophical discourse, albeit in new guises.

- Personal Identity: What makes me the same person from childhood to old age, despite profound changes in my physical and mental attributes? Is it continuity of memory, consciousness, or some underlying substance?

- Mereology: The study of parts and wholes. When does a collection of parts constitute a single, same entity, and when does it remain a mere aggregate of other parts?

- Philosophy of Language: How do proper names refer to the same individual across different contexts and times? What allows us to distinguish one referent from others?

- Modal Logic: Exploring possibilities and necessities, often involves asking what properties a thing could have while remaining the same thing, versus properties that would make it an other thing entirely.

The foundational questions posed by Parmenides, refined by Plato and Aristotle, and dynamically reinterpreted by Hegel, remain central to understanding the very nature of Being and our capacity to think coherently about it. The interplay of Same and Other is not a peripheral concern but the very engine of metaphysical inquiry.

Conclusion: The Unfolding Logic of Existence

The concepts of Same and Other are not mere categories in a philosophical lexicon; they are the fundamental logic through which we apprehend and articulate reality. From the stark monism of Parmenides to Plato's elegant solution in the Sophist, Aristotle's robust system of substance, and Hegel's dynamic dialectic, the philosophical tradition has ceaselessly grappled with how to distinguish and relate identity and difference. This enduring pursuit highlights their indispensable role in any coherent account of Metaphysics and the nature of Being. To understand what something is, we must simultaneously understand what it is not, engaging in the perpetual, unfolding dance of Same and Other.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Plato Sophist Explained"

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Hegel Dialectic Identity and Difference"