The Inextricable Tapestry: Unraveling the Logic of Quantity and Relation

In the grand edifice of philosophical inquiry, few concepts are as foundational, yet as deceptively simple, as quantity and relation. They are not merely abstract notions but the very scaffolding upon which we build our understanding of the cosmos, from the smallest particle to the grandest galaxy, and indeed, our place within it. This article delves into the profound logic that underpins these concepts, exploring how thinkers throughout the history of Western thought, from the ancient Greeks to modern logicians, have grappled with their nature, their interplay, and their ultimate expression in mathematics. We shall see that to understand quantity is to measure existence, and to grasp relation is to comprehend the fabric of connection, both inextricably bound by the rigorous demands of logic.

The Indispensable Nexus: Quantity and Relation

Our world, as we perceive and conceptualize it, is defined by what is and how it connects. These two fundamental modes of apprehension are encapsulated by quantity and relation. Without a grasp of how many, how much, or how extensive, our perception would lack dimension. Without an understanding of how one thing stands in connection to another—be it cause, effect, similarity, or difference—our universe would be an incoherent jumble of isolated particulars.

Quantity: The Measure of Being

The notion of quantity has captivated philosophers since antiquity. It speaks to the measurable aspects of existence—number, magnitude, duration, extension. For the Pythagoreans, numbers were not just symbols but the very essence of reality, the underlying harmony of the universe. Plato, in his theory of Forms, posited ideal mathematical entities as perfect archetypes, with the sensible world being but an imperfect reflection. Aristotle, in his Categories, formally classified quantity as one of the ten fundamental ways in which being can be predicated, distinguishing between discrete quantities (like numbers, where parts are separate) and continuous quantities (like lines or time, where parts are joined).

Consider the progression of thought regarding quantity:

- Ancient Greece:

- Pythagoras: "All is number." The universe is governed by mathematical ratios.

- Plato: Ideal Forms of numbers and geometric figures exist independently, providing perfect models for the physical world.

- Aristotle: Quantity as a category of being, differentiating between numerical (discrete) and spatial/temporal (continuous) measures.

- Medieval Period: Scholastic philosophers debated the nature of infinitesimals and the quantification of theological concepts, pushing the boundaries of logical reasoning about the boundless.

- Early Modern Era: Descartes's analytic geometry unified algebra and geometry, allowing spatial relations (quantities) to be expressed algebraically, a monumental step in understanding measurable reality. Leibniz's development of calculus provided tools to analyze continuously changing quantities, revolutionizing our understanding of motion and growth.

The very act of counting, measuring, or comparing sizes and durations is an engagement with the logic of quantity. It requires consistent rules, definitions, and operations to yield meaningful results.

Relation: The Fabric of Connection

If quantity tells us what something is in terms of its extent, relation tells us how it stands to other things. Causality, similarity, difference, position, parentage—these are all forms of relation. Aristotle also identified relation as a key category, noting that things are said to be relative when their very being depends on their connection to another, like a "master" to a "slave" or "knowledge" to "the knowable."

The philosophical journey through relation has been particularly fraught:

- Hume's Skepticism: David Hume famously questioned the logical necessity of cause-and-effect relations, arguing that we only observe constant conjunction, not an inherent necessary connection. This challenged the very foundation of scientific and empirical understanding.

- Kant's Synthesis: Immanuel Kant responded to Hume by positing that relations like causality are not merely empirical observations but categories of understanding inherent in the mind. They are the necessary frameworks through which we organize our sensory experience, making objective knowledge possible.

- Modern Logic: The development of predicate logic by Frege, Russell, and others allowed for the formalization of relations beyond simple subject-predicate statements. Propositions like "A is taller than B" or "X causes Y" could be rigorously analyzed, revealing the complex logical structures underlying relational statements.

Consider the diverse forms relations can take:

| Type of Relation | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Causal | One event or state brings about another. | Heat causes expansion; rain causes puddles. |

| Comparative | Establishes a difference or similarity in degree. | Taller than, equal to, brighter than. |

| Spatial | Defines position or proximity. | To the left of, above, inside. |

| Temporal | Defines order in time. | Before, after, simultaneous with. |

| Logical | Implies a necessary connection based on reason or definition. | If P, then Q; is a type of. |

The logic of relation requires careful attention to transitivity, symmetry, reflexivity, and other properties that govern how relations behave and how we can reason about them.

Logic: The Architect of Understanding

At the heart of both quantity and relation lies logic. Logic is the study of correct reasoning, the principles by which we can distinguish valid arguments from invalid ones. From Aristotle's syllogistic logic, which provided a framework for deductive reasoning, to the symbolic logic of the 20th century, logic has provided the tools to analyze, clarify, and formalize our understanding of these fundamental concepts.

- Aristotelian Logic: Provided the first systematic treatment of inference, demonstrating how conclusions necessarily follow from premises. This was crucial for understanding how quantitative statements ("All men are mortal, Socrates is a man, therefore Socrates is mortal") and relational statements ("If all A are B, and all B are C, then all A are C") could be rigorously evaluated.

- Leibniz's Dream: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz envisioned a "calculus ratiocinator," a universal logical language that could resolve all disputes through calculation, much like mathematics resolves quantitative problems. This foreshadowed modern symbolic logic.

- Modern Symbolic Logic: Frege, Russell, Whitehead, and others developed powerful systems of logic that could express complex quantitative and relational statements with unprecedented precision. Principia Mathematica by Russell and Whitehead, for instance, attempted to derive all of mathematics from purely logical principles, highlighting the deep interconnections.

The logical principles of consistency, non-contradiction, and sufficient reason are indispensable when dealing with quantities (e.g., a number cannot be both even and odd simultaneously) and relations (e.g., if A is a parent of B, B cannot simultaneously be a parent of A in the same sense).

Mathematics: The Language of Precision

Ultimately, mathematics emerges as the most sophisticated language for expressing and exploring the logic of quantity and relation. It is the realm where these concepts achieve their purest, most abstract, and most powerful forms. From Euclidean geometry's axioms defining spatial quantities and relations to the intricate equations of physics describing causal relations between quantified variables, mathematics provides the framework.

- Geometry: Euclidean geometry, as presented in The Elements, is a prime example of a deductive system built upon fundamental definitions, postulates, and common notions. It explores spatial quantities (lines, angles, areas) and their relations with unparalleled logical rigor.

- Algebra: Provides a symbolic means to express general quantitative relations, allowing for the solution of problems involving unknown quantities.

- Calculus: Offers tools to analyze change and accumulation, dealing with quantities that vary continuously and the rates at which they relate to each other.

- Set Theory: Provides a foundational language for defining collections of objects and the relations between them, underpinning much of modern mathematics and logic.

Mathematics, far from being a mere tool, is a profound philosophical endeavor that reveals the inherent structures of reality and thought concerning quantity and relation. It pushes the boundaries of our logical capacity, allowing us to conceive of infinites, complex numbers, and multi-dimensional spaces, all while maintaining internal consistency and rigor.

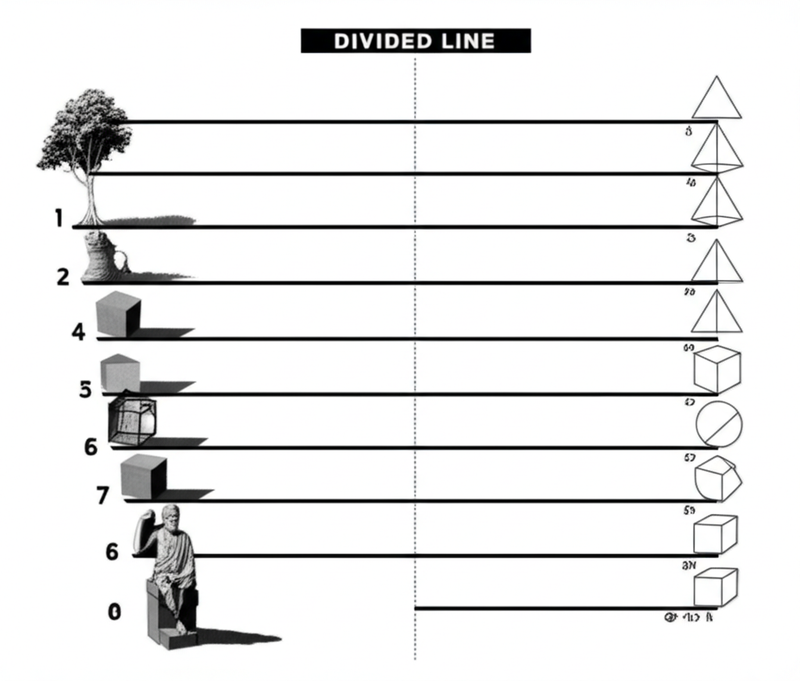

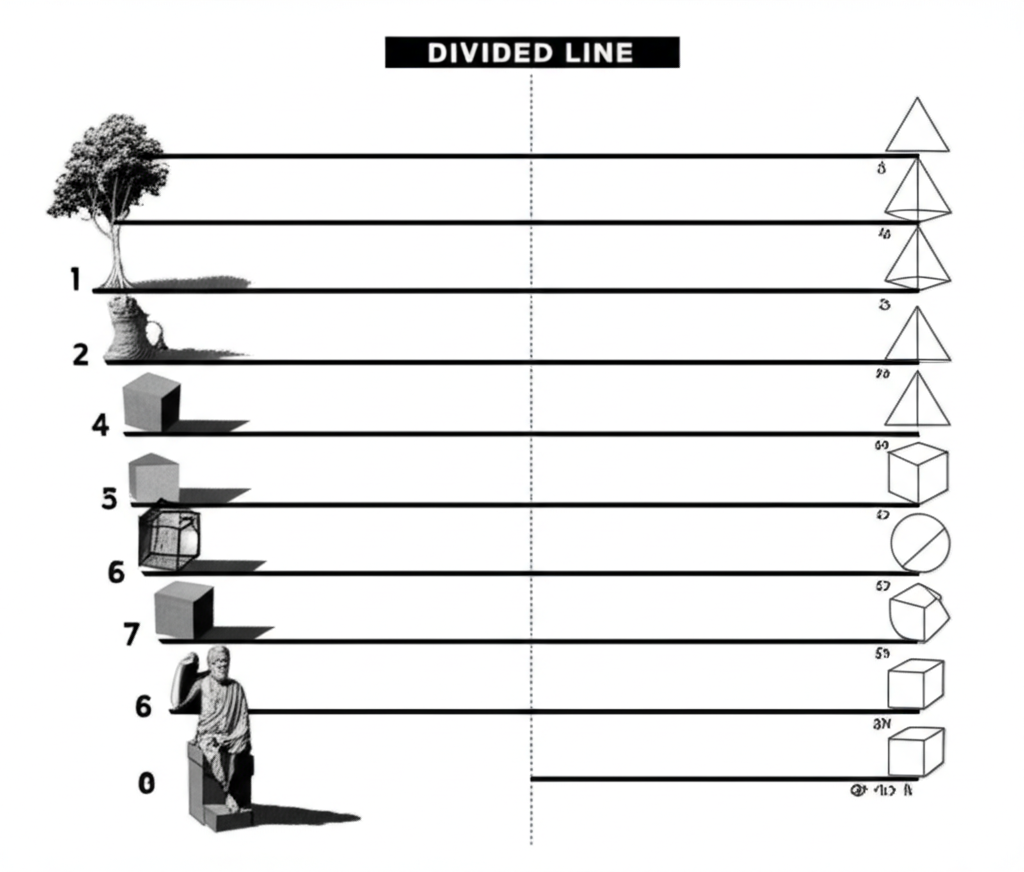

transitioning to the Forms themselves, with the Sun representing the Form of the Good, all structured with clear demarcations and labels for different levels of reality and knowledge. The lines are drawn with a classical, perhaps slightly faded, parchment aesthetic.)

transitioning to the Forms themselves, with the Sun representing the Form of the Good, all structured with clear demarcations and labels for different levels of reality and knowledge. The lines are drawn with a classical, perhaps slightly faded, parchment aesthetic.)

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Great Books of the Western World: Aristotle's Categories""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: KANT ON: What is Enlightenment?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Hume's Problem of Causation Explained Simply""