The Logic of Opposition: Navigating Contradiction in Thought

For those of us at planksip, delving into the intricacies of human thought often leads us to fundamental concepts that underpin our very understanding of the world. One such concept, both ubiquitous and profound, is opposition. Far from being merely a source of conflict or disagreement, the logic of opposition is a cornerstone of reasoning, a dynamic force that shapes our perceptions, refines our ideas, and propels philosophical inquiry forward. It is through the encounter with what stands against, what contrasts, and what contradicts, that our understanding truly deepens, revealing the nuanced tapestry of reality.

The Ubiquity of Opposition in Our World

From the simplest binary choices we make daily to the grandest philosophical debates, opposition is an inescapable element of experience. Light versus dark, good versus evil, true versus false—these are not just abstract pairings but fundamental structures through which we apprehend and categorize the world. To understand one concept often requires an implicit, or explicit, understanding of its opposite. This inherent duality is not a flaw in our cognitive apparatus but rather a powerful tool, a mechanism by which we define, distinguish, and ultimately, comprehend.

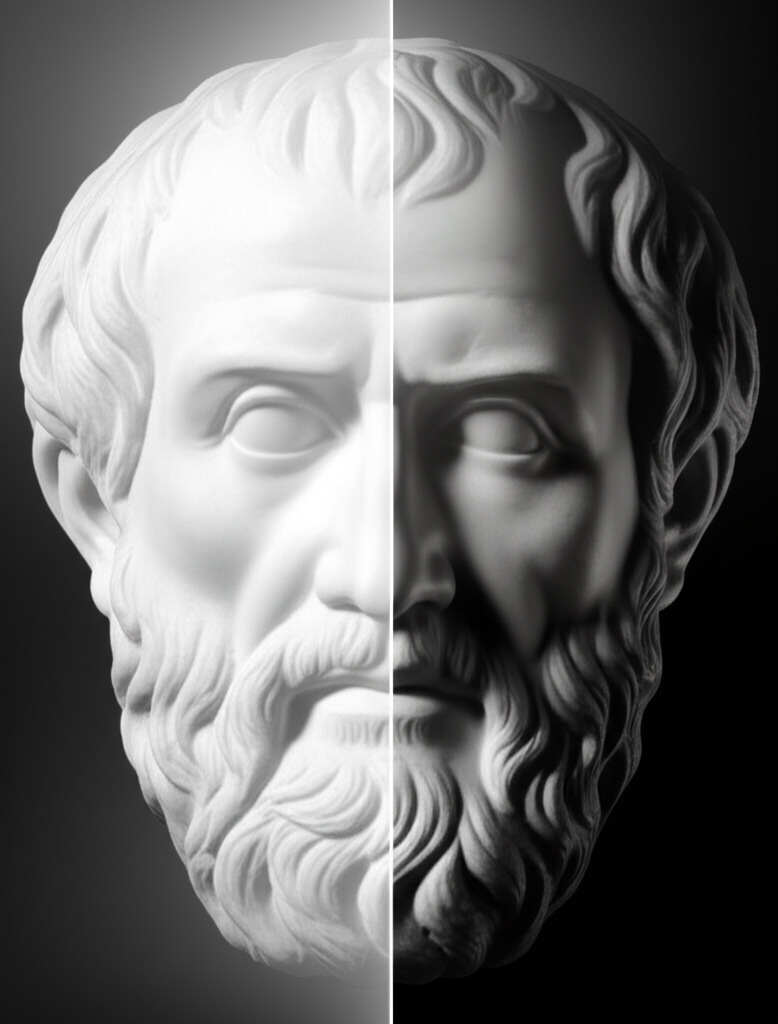

Aristotle's Enduring Foundations: Categorizing Opposition

Our journey into the logic of opposition must inevitably begin with the foundational work of Aristotle, whose meticulous analyses in the Organon (a key component of the Great Books of the Western World) laid the groundwork for Western thought. Aristotle didn't just acknowledge opposition; he systematically categorized it, providing us with a framework that remains remarkably insightful. He understood that opposition was not a monolithic concept but manifested in several distinct forms, each with its own implications for reasoning.

Aristotle identified four primary types of opposition:

- Contradiction (Antiphasis): This is the most absolute form, where one statement is the direct negation of another, and both cannot be true (and both cannot be false) simultaneously. For example, "Socrates is sitting" versus "Socrates is not sitting." This binary is fundamental to the law of non-contradiction.

- Contrariety (Enantia): Here, two extremes exist within the same genus, and while both cannot be true at the same time, both can be false. For instance, "Socrates is well" versus "Socrates is ill." A person can be neither well nor ill, but merely indifferent.

- Privation (Steresis): This involves the absence of a quality that something should naturally possess. Sight versus blindness, or knowledge versus ignorance, are examples. It's not merely the opposite, but the lack of a specific attribute where it would normally be present.

- Relation (Pros Ti): This type of opposition describes concepts that are inherently defined by their relationship to another, such as double versus half, or master versus slave. One cannot exist or be understood without the other.

These distinctions are crucial because they inform how we construct arguments, evaluate claims, and ultimately, engage in sound reasoning. Misunderstanding the type of opposition at play can lead to fallacies and flawed conclusions.

From Ancient Logic to the Dynamic of Dialectic

While Aristotle provided the formal structure for understanding static oppositions, the concept of dialectic elevates opposition into a dynamic process. Plato, another titan from the Great Books, frequently employed the dialectic method in his dialogues. For Plato, truth was not simply stated but emerged from the rigorous back-and-forth of opposing viewpoints, challenging assumptions and refining understanding through a series of questions and answers. The tension between ideas was not to be avoided but embraced as the very engine of philosophical discovery.

Centuries later, G.W.F. Hegel profoundly reinterpreted dialectic as the fundamental process of thought and reality itself. His famous triad of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis describes a progression where an initial idea (thesis) inevitably generates its opposite (antithesis), and the conflict between them leads to a higher, more complex understanding (synthesis). This synthesis then becomes a new thesis, perpetuating the cycle of intellectual and historical development. For Hegel, opposition was not a static logical category but a vibrant, generative force driving the evolution of consciousness and history.

The Productive Power of Opposition

The journey through the logic of opposition, from Aristotle's meticulous categories to Hegel's grand dialectic, reveals a profound truth: opposition is not merely an obstacle to be overcome, but often the very catalyst for progress and deeper insight. It forces us to scrutinize our assumptions, to test the robustness of our arguments, and to consider alternative perspectives. Without the friction of opposing ideas, our thoughts might remain stagnant, unchallenged, and ultimately, incomplete.

Embracing the logic of opposition means recognizing that disagreement can be fertile ground for growth. It means understanding that contradictory viewpoints, when engaged with thoughtful reasoning, can lead to a more comprehensive and nuanced grasp of complex issues. In a world often polarized by seemingly irreconcilable differences, the philosophical tradition offers us a powerful reminder: the tension of opposition, when properly understood and navigated, is not an end but a beginning—a gateway to new knowledge and a more profound understanding of ourselves and the universe we inhabit.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Aristotle on Contradiction and Contrariety," "Hegel's Dialectic Explained""