The Enduring Riddle: How Experience Shapes Our Logic of Induction

Summary: Induction, the process of deriving general principles from specific observations, forms the bedrock of much of our knowledge about the world. Yet, its logic is not one of certainty, but of probability, fundamentally reliant on past experience. This article explores the nature of induction, its indispensable role in everyday life and scientific inquiry, and the profound philosophical challenges it presents, particularly regarding its justification, inviting us to ponder the very foundations of our understanding.

I. Introduction: The Unseen Architect of Our Worldview

My dear reader, have you ever paused to consider how much of what you know about the world isn't derived from undeniable, self-evident truths, but rather from a profound, almost unconscious leap of faith? We observe the sun rising day after day, and we expect it to rise tomorrow. We touch fire, it burns, and we conclude it will burn again. This isn't mere habit; it's the very fabric of our practical knowledge, woven by a process philosophers call induction. It's the unseen architect that builds our expectations, shapes our sciences, and allows us to navigate a world that never quite repeats itself identically. But what is the true logic behind this fundamental human enterprise? And what role does our accumulated experience play in its precarious dance?

II. Defining Induction: From Particulars to Universals

At its core, induction is a form of reasoning that moves from specific observations or instances to broader generalizations or theories. Unlike deduction, which guarantees the truth of its conclusion if its premises are true (e.g., "All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal"), induction offers no such certainty. Its conclusions are, at best, probable.

Consider these examples:

- Observation 1: Every swan I have ever seen is white.

- Observation 2: Every swan my colleagues have seen is white.

- Inductive Conclusion: All swans are white.

This seems reasonable, doesn't it? Until, of course, one encounters a black swan in Australia, as indeed happened to European explorers. This simple illustration highlights both the power and the peril of inductive reasoning. It allows us to build predictive models, yet it remains perpetually open to revision by new experience.

III. The Indispensable Role of Experience

It is impossible to discuss induction without placing experience at its very heart. For the empiricists, from John Locke to David Hume, our minds are initially tabula rasa – blank slates – upon which experience inscribes its lessons. We don't arrive with innate knowledge of gravity or the properties of fire; we learn these through repeated observations and interactions with the world.

- Foundation of Beliefs: Our belief in cause and effect, for instance, is not a logical necessity but an acquired expectation based on constant conjunctions observed in experience. When we see a cue ball strike an eight ball, and the eight ball moves, we infer a causal link, not because we deduce it, but because we have experienced similar sequences countless times.

- Scientific Inquiry: The scientific method itself is a grand exercise in induction. Scientists gather data (specific observations), formulate hypotheses (generalizations), and test them through experiments, continually refining their theories based on new experience. From the laws of physics to biological classifications, induction is the engine of scientific progress.

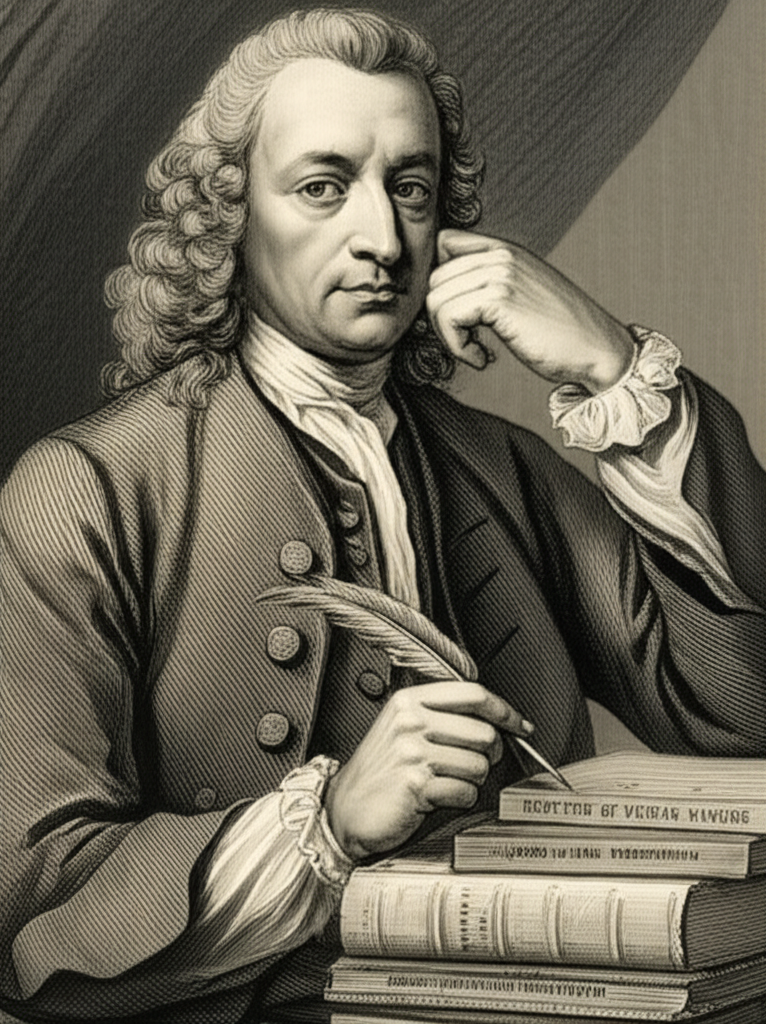

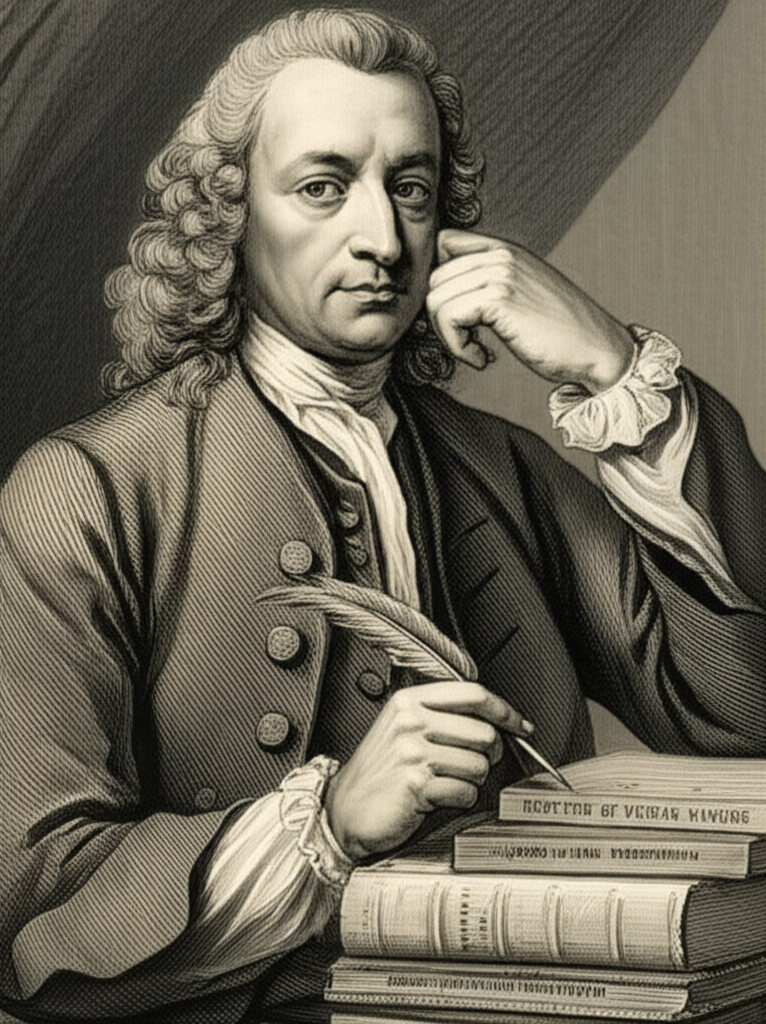

IV. Hume's Challenge: The Problem of Induction

Perhaps the most profound philosophical challenge to the logic of induction came from the Scottish philosopher David Hume in the 18th century. Hume observed that our inductive inferences rely on an unstated premise: the belief that the future will resemble the past, or that unobserved instances will resemble observed instances. This assumption, known as the Principle of the Uniformity of Nature, is itself justified only by past experience.

- The Circularity: We believe the sun will rise tomorrow because it always has. Why should it always rise? Because nature is uniform. How do we know nature is uniform? Because it has always been uniform in our experience. This, Hume argued, is a circular argument. It uses induction to justify induction, offering no independent logical basis.

- Beyond Logic: Hume concluded that our belief in inductive inferences is not a matter of logic or reason, but rather a matter of custom or habit. It's a psychological necessity, not a rational one. This insight shook the foundations of epistemology and remains a central problem in philosophy.

V. Grappling with Hume: Philosophical Responses

Hume's problem has spurred centuries of philosophical debate. While no definitive "solution" has been universally accepted, various approaches attempt to address the precarious nature of inductive knowledge:

| Philosophical Approach | Key Idea | Relationship to Induction |

|---|---|---|

| Pragmatism | Induction works in practice. | While not logically certain, induction is indispensable for practical action and scientific progress. We must assume its efficacy to function. |

| Falsificationism (Popper) | Science progresses by disproving, not proving. | Inductive generalizations can never be proven true, only falsified. The best theories are those that have withstood the most rigorous attempts at falsification. |

| Bayesianism | Probabilistic reasoning. | Induction is about updating our degrees of belief based on new evidence. We start with prior probabilities and adjust them as new experience comes in. |

| Analytic Philosophy | Re-examining the language of "justification." | Some argue that asking for a "justification" of induction is a category error; induction is what we mean by rational inference about the unobserved. |

These responses highlight that while the logic of induction may not be deductive, its utility and the ways we manage its inherent uncertainty are central to our pursuit of knowledge.

VI. Induction in Action: From Daily Life to Grand Theories

Despite its philosophical challenges, induction is not merely an academic concern; it is profoundly practical.

- Everyday Life: We make inductive leaps constantly. When we taste a new food, we expect the next bite to taste similar. When we meet a new person, we form initial impressions and predict their future behavior based on past interactions with others. Our very survival depends on our ability to generalize from experience.

- Scientific Advancement: From formulating general laws (like Newton's laws of motion, derived from countless observations of falling apples and moving planets) to the development of modern medicine (testing drugs on samples to infer effects on populations), induction is the engine of scientific discovery. Without it, science would be reduced to mere cataloging of individual facts, incapable of prediction or explanation.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Knowledge

The logic of induction and its profound reliance on experience present us with one of philosophy's most enduring riddles. It is a form of reasoning that, while lacking the ironclad certainty of deduction, remains utterly indispensable for building our knowledge of the world. Hume's skeptical challenge forces us to acknowledge the inherent uncertainty, the leap of faith, involved in projecting past regularities into the future. Yet, it is precisely this ability to learn from experience, to generalize, to predict, and to adapt, that has allowed humanity to thrive and to construct the vast edifice of scientific understanding.

As we navigate our complex world, we are constantly engaged in this inductive dance, refining our generalizations with every new piece of experience. The quest for knowledge, it seems, is less about discovering absolute certainties and more about skillfully managing probabilities, always with an open mind to the unexpected black swan that might challenge our deepest assumptions.

YouTube Video Suggestions:

-

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Hume's Problem of Induction Explained""

2. ## 📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: ""Inductive vs Deductive Reasoning Crash Course Philosophy""