The Enduring Logic of Change in Element

The universe, in its dizzying complexity, presents no more fundamental a puzzle than that of change. From the ceaseless flow of a river to the metamorphosis of a caterpillar, and indeed, to the very transformations of the cosmos's most basic constituents, change is an undeniable reality. Yet, how do we logically understand something that is, by its very nature, never quite the same? This article delves into the philosophical inquiry of the logic of change in element, tracing its roots from ancient Greek thought, as preserved in the Great Books of the Western World, to its enduring implications for our understanding of physics and reality itself. We will explore how philosophers grappled with the apparent paradoxes of transformation, seeking a rational framework to reconcile flux with persistence, and how their insights continue to resonate in our contemporary understanding of the world's fundamental constituents.

The Ancient Riddle: Being, Becoming, and the Element

The earliest Western philosophers were captivated by the problem of change. How can something be and not be simultaneously? If an element transforms, does it cease to exist entirely, or does some part of it persist? This fundamental question lies at the heart of our inquiry into the logic of change in element.

Consider the foundational debates that shaped philosophical thought:

- Heraclitus of Ephesus: Famously declared that "everything flows" (panta rhei), likening existence to a river one can never step into twice. For Heraclitus, change was the ultimate reality, with fire often cited as his primary element due to its constant state of transformation.

- Parmenides of Elea: Stood in stark opposition, arguing that change is an illusion. True Being is eternal, unchanging, and singular. If something changes, it must pass from being to non-being, which is logically impossible.

This dichotomy presented a profound challenge: how could logic accommodate the observable reality of change without falling into contradiction? The answer lay in a more nuanced understanding of what it means for an element to change.

Aristotle's Masterful Synthesis: Potency, Act, and the Four Causes

It was Aristotle, drawing extensively from his predecessors and meticulously cataloging the logic of the natural world, who offered a compelling framework to reconcile these opposing views. His philosophy, a cornerstone of the Great Books, provided a robust logic for understanding change in elements without denying either their persistence or their transformation.

Aristotle introduced the concepts of potency (potentiality) and act (actuality). An element doesn't simply cease to be and then become something entirely new; rather, it moves from being potentially one thing to being actually another.

Consider a simple example: a block of wood.

- It is actually wood.

- It is potentially a table, or ashes, or charcoal.

When the wood changes into a table, its potential as a table is actualized. When it burns into ashes, its potential to be ashes is actualized. The wood itself, in some sense, ceases to be qua wood, but the underlying matter persists, taking on a new form.

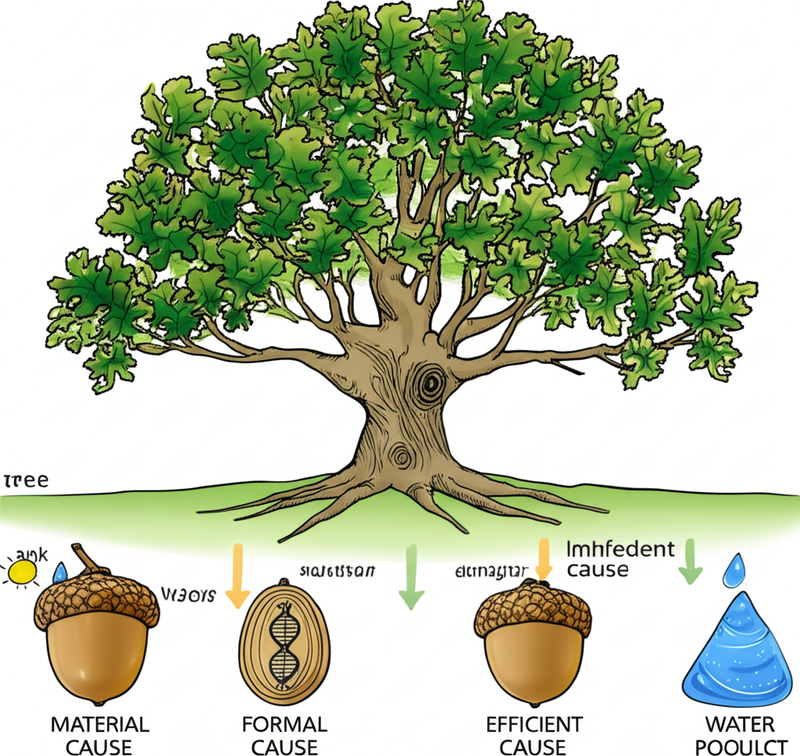

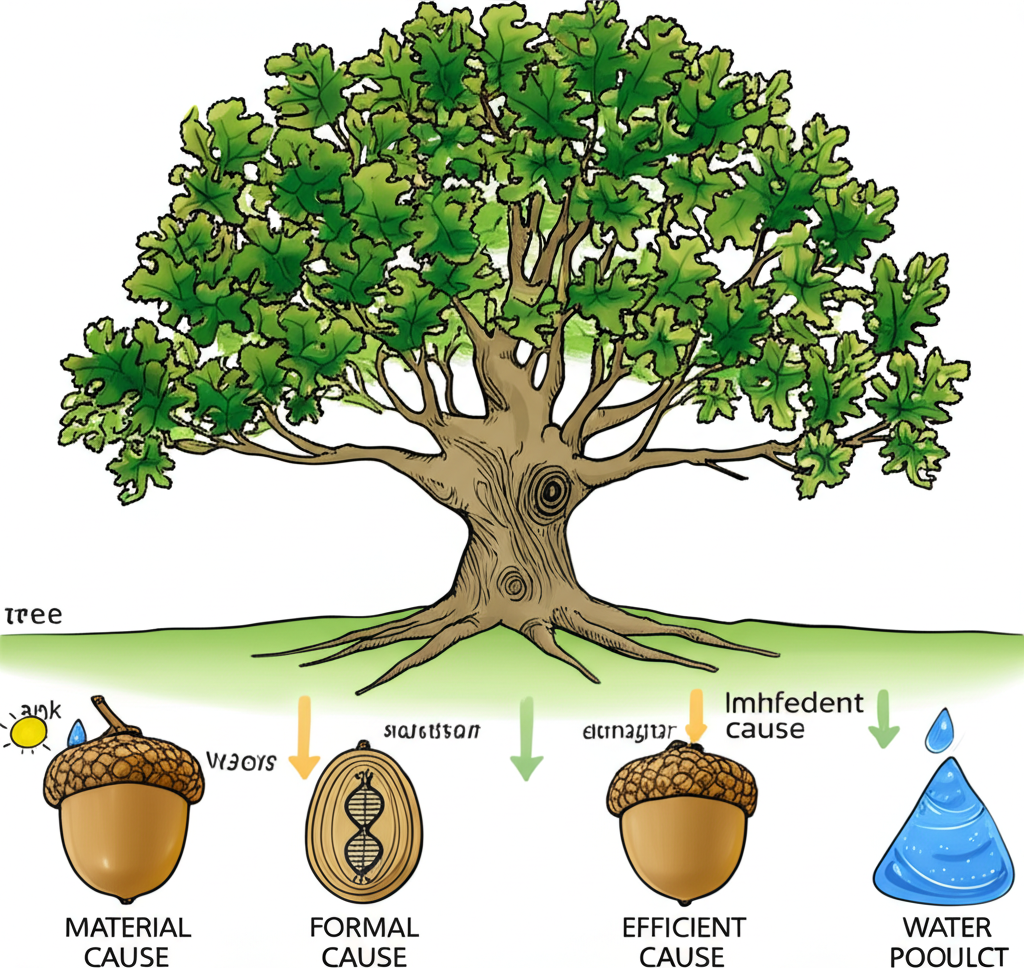

To further elaborate on the logic of change, Aristotle proposed his Four Causes:

| Cause | Description | Example: A Statue of David |

|---|---|---|

| Material Cause | That out of which something comes to be and persists. | The marble from which the statue is carved. |

| Formal Cause | The form or pattern of the thing; its essence. | The design or shape of David that Michelangelo conceived. |

| Efficient Cause | The primary source of the change or rest. | Michelangelo himself, the sculptor. |

| Final Cause | The end, purpose, or goal for the sake of which a thing is done. | The artistic expression, the beauty, the glorification of God. |

For an element to change, especially in the ancient context of physics where earth, air, fire, and water were considered fundamental, it wasn't a sudden annihilation and creation. Instead, it was often conceived as a transformation of underlying matter from one form to another, driven by an efficient cause towards a final state. The logic here is that change is not arbitrary but proceeds according to intelligible principles.

The Element in Modern Physics: A Deeper Logic of Transformation

While ancient physics posited four fundamental elements, modern science has revealed a vastly more intricate periodic table of chemical elements and an even more complex subatomic world. Yet, the logic of change articulated by Aristotle remains surprisingly relevant.

In modern physics, elements are defined by the number of protons in their nucleus. When an element changes – say, through radioactive decay or nuclear fusion – it undergoes a profound transformation. Uranium decays into lead, or hydrogen fuses into helium in stars. This is not merely a rearrangement of parts but a fundamental alteration of the element's identity.

However, even in these radical transformations, a logic of persistence and potentiality can be observed:

- Conservation Laws: Energy, momentum, and charge are conserved even when elements transform. This implies an underlying substrate of reality that endures.

- Subatomic Constituents: The elements are composed of quarks and leptons. When one element transforms into another, these more fundamental particles are rearranged or transmuted according to strict quantum physics rules, not arbitrary disappearance and appearance.

The logic of change here is incredibly complex, governed by the laws of quantum mechanics, but it is still a logic – a set of rules and principles that dictate how elements can and do transform, moving from one state of actuality to another through various potentials.

The Logical Necessity of Persistence Amidst Flux

The core philosophical insight, enduring from ancient thought to modern science, is that for change to be intelligible, there must be something that persists through the change. If absolutely nothing persisted, we would not speak of change but of annihilation and spontaneous creation.

- For ancient philosophers, this might have been an underlying substrate, a form, or simply the very notion of "matter."

- For modern physics, it's the conservation laws, the enduring subatomic particles, and the fundamental fields that govern their interactions.

The logic dictates that for an element to change, it must retain some identity, some connection to its former self, even as it becomes something new. This isn't a contradiction but a sophisticated understanding of being and becoming, where potentiality bridges the gap between different actual states. Without this logic, the universe would be an utterly chaotic and unintelligible series of unconnected events, rather than a cosmos of continuous, albeit transforming, existence.

Conclusion: The Unifying Logic of Elemental Metamorphosis

The journey through the logic of change in element reveals a profound continuity in philosophical inquiry. From the stark opposition of Heraclitus and Parmenides, through Aristotle's elegant synthesis of potency and act, to the intricate transformations described by modern physics, the human mind has consistently sought a rational framework for understanding the dynamic nature of reality.

The Great Books of the Western World remind us that these are not merely historical curiosities but foundational questions that continue to shape our understanding of existence. Whether we speak of ancient elements or the complex atomic structures of today, the logic of transformation demands that we account for both the enduring substrate and the evolving form. It is this enduring logic that allows us to perceive a coherent, albeit ever-changing, universe, where every element's metamorphosis is a testament to the intricate dance between potential and actuality.

📹 Related Video: ARISTOTLE ON: The Nicomachean Ethics

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Aristotle Four Causes Explained"

📹 Related Video: PLATO ON: The Allegory of the Cave

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "Ancient Greek Elements and Modern Chemistry"