The Philosophical Odyssey of Space in Mathematics

Summary: The concept of space, seemingly intuitive, has undergone a profound and complex evolution, transitioning from a perceived physical container to an abstract mathematical construct. This pillar page embarks on a philosophical journey, tracing the idea of space from ancient geometric axioms to modern topological spaces and the fabric of spacetime. We will explore how philosophers and mathematicians, drawing from works within the Great Books of the Western World, have continuously redefined and expanded our understanding of this fundamental quantity, revealing its multifaceted nature as both a backdrop for existence and a product of mathematical abstraction. This exploration highlights the enduring interplay between human intuition, philosophical inquiry, and rigorous mathematics in shaping one of our most essential concepts.

Introduction: Beyond the Void – Unpacking the Idea of Space

From the moment we open our eyes, we perceive a world unfolding within space. It's the arena where events occur, where objects have extension, and where distances are measured. Yet, what is this space? Is it a tangible entity, an empty void, or merely a construct of our minds? For millennia, this fundamental idea has captivated the greatest thinkers, leading to profound developments not only in philosophy but, crucially, in mathematics.

The journey of understanding space is not linear; it's a rich tapestry woven with philosophical debates, scientific discoveries, and revolutionary mathematical insights. This article delves into how the quantity of space—its dimensions, properties, and very existence—has been conceptualized and formalized through the lens of mathematics, from the ancient Greeks to the abstract realms of modern topology. Our exploration will reveal that the idea of space is far more dynamic and less settled than everyday experience might suggest.

Ancient Foundations: Geometry, Cosmos, and the Idea of Place

The earliest attempts to formalize the idea of space are found in ancient Greece, where geometry emerged as the quintessential mathematical discipline.

Euclid's Axiomatic Universe

Perhaps no single work has shaped our understanding of space more profoundly than Euclid's Elements. Within this monumental text, space is presented axiomatically, built upon definitions of points, lines, and planes. Here, space is understood as a boundless, continuous quantity, governed by a set of self-evident truths or postulates.

- Points, Lines, Planes: The fundamental building blocks, defining position and extension without inherent size.

- Axioms and Postulates: Statements like "a straight line may be drawn between any two points" laid the groundwork for a deductive system that described the properties of spatial figures.

- The Fifth Postulate: Euclid's famous parallel postulate, which states that through a point not on a given line, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to the given line, would later become the flashpoint for revolutionary developments in non-Euclidean geometries.

For Euclid, the idea of space was intrinsically linked to the measurable properties of shapes and figures within it. It was a static, homogeneous backdrop for all geometric operations.

Plato's Receptacle and Aristotle's Place

While Euclid provided the mathematical framework, philosophers like Plato and Aristotle grappled with the metaphysical nature of space.

- Plato's Timaeus: Plato introduced the concept of the "Receptacle" (chora), a formless, invisible, and all-receiving medium in which the Forms impress themselves to create the sensible world. It's not space as we typically conceive it, but rather a primordial quantity or substratum for existence, hinting at an underlying reality that contains all things.

- Aristotle's Physics: Aristotle rejected the notion of an infinite void. For him, "place" (topos) was the inner boundary of the containing body. Space, therefore, was not an independent entity but rather a property derived from the relationship between objects. An object's place was defined by what immediately surrounded it. This relational idea of space stood in stark contrast to later conceptions of absolute space.

Table 1: Ancient Ideas of Space

| Thinker | Primary Conception of Space | Key Text / Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Euclid | Axiomatic, boundless, continuous quantity for geometric forms. | Elements (geometric formalization) |

| Plato | The "Receptacle" (chora) – a formless substratum for creation. | Timaeus (metaphysical concept) |

| Aristotle | "Place" (topos) – the inner boundary of a containing body; relational. | Physics (rejection of void, relational space) |

The Renaissance Shift: Descartes and the Birth of Analytical Geometry

The scientific revolution brought a radical transformation to the idea of space, largely spearheaded by René Descartes.

Space as Extension: Res Extensa

In his Meditations and Principles of Philosophy, Descartes fused algebra with geometry, creating analytical geometry. This monumental achievement allowed geometric problems to be solved algebraically and vice-versa, providing a powerful new mathematical language for describing space. For Descartes, the very essence of matter was extension (res extensa)—its length, breadth, and depth. Space, therefore, was not merely a container but was identical with matter itself. An empty space was a contradiction; where there was extension, there was matter. This idea deeply influenced subsequent philosophical and scientific thought, grounding the physical world in a quantifiable, mathematical framework.

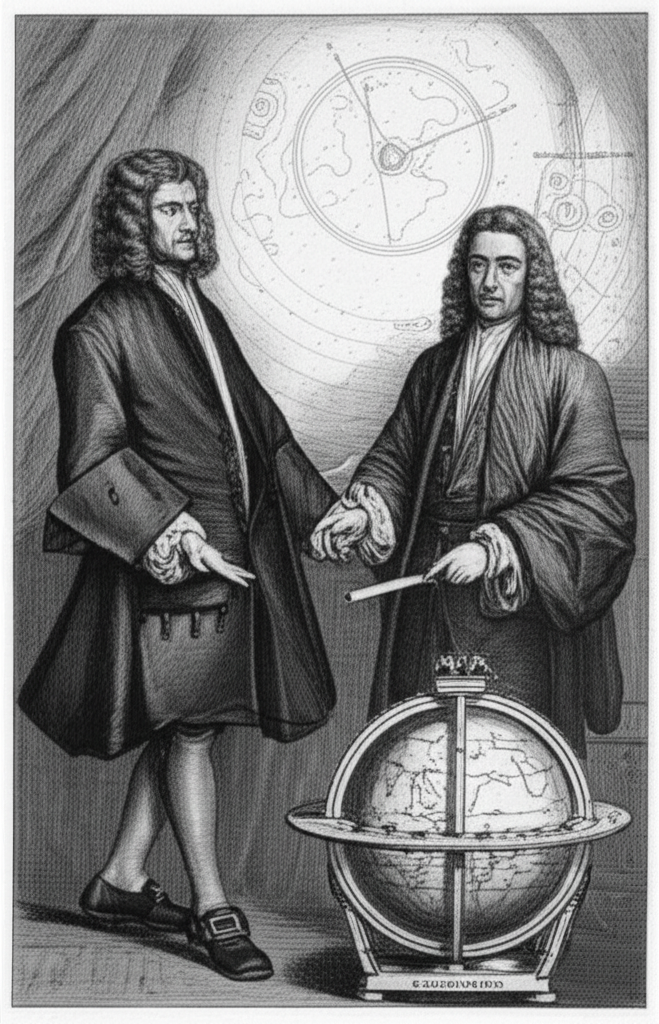

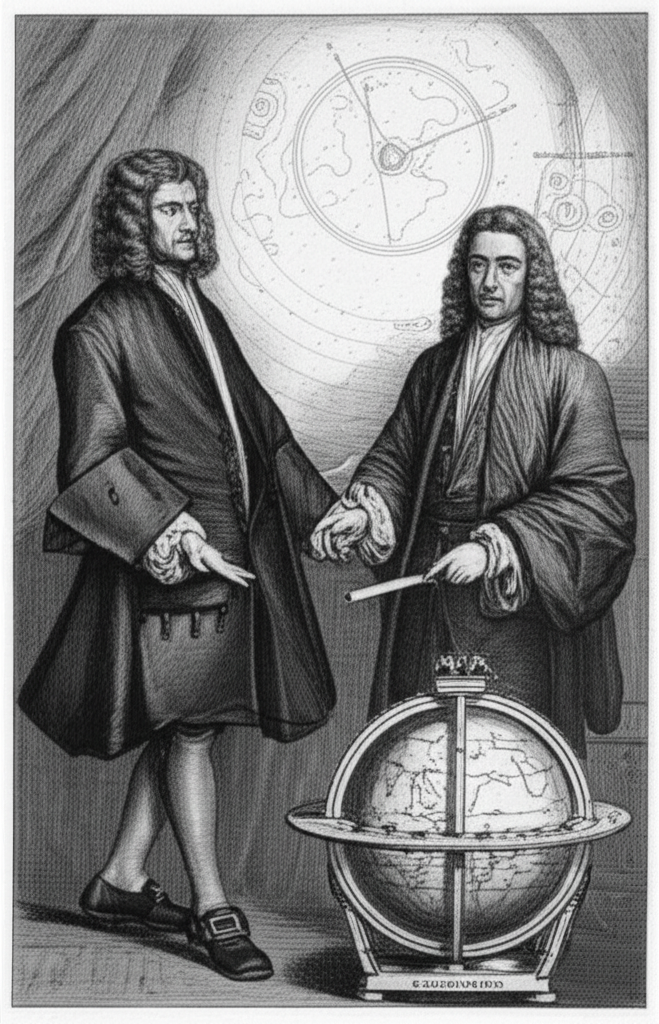

The Great Debate: Newton, Leibniz, and the Nature of Reality

The 17th century witnessed one of the most significant philosophical debates concerning the nature of space, primarily between Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. This controversy, often framed around the quantity of space, highlighted whether space was an absolute entity or a relational concept.

Newton's Absolute Space

In his Principia Mathematica, Newton posited the existence of absolute space: a homogeneous, isotropic, infinite, and immutable entity that exists independently of any objects within it. It acts as a universal frame of reference against which all motion can be measured. Newton famously described it as God's "sensorium"—a divine omnipresence. This idea was crucial for his mechanics, allowing for concepts like absolute velocity and acceleration. For Newton, space was a real, substantial quantity, though intangible.

Leibniz's Relational Space

Leibniz vehemently opposed Newton's absolute space. For him, space was not an independent substance but merely "the order of coexisting phenomena." It was a system of relations between objects, much like time was the order of successive events. If there were no objects, there would be no space. Leibniz argued that absolute space violated the principle of sufficient reason (why would God place the universe here rather than there if space were truly absolute and uniform?) and the principle of indiscernibles (two identical universes shifted in absolute space would be indistinguishable, making the shift meaningless). His idea of space was entirely relational, derived from the arrangement and interaction of matter.

Table 2: Absolute vs. Relational Space

| Feature | Newton's Absolute Space | Leibniz's Relational Space |

|---|---|---|

| Existence | Exists independently of objects; a real, substantial quantity. | Merely an order of relations among objects; no existence without them. |

| Nature | Homogeneous, isotropic, infinite, immutable; God's sensorium. | Derived from the properties and positions of actual things. |

| Motion | Absolute motion is possible and measurable against fixed space. | Only relative motion is meaningful; motion is change in relations. |

| Implications | Provides a universal, objective frame of reference. | Emphasizes the interconnectedness of the universe; no empty space. |

Kant and the Transcendental Nature of Space

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, offered a revolutionary synthesis to the debate, suggesting that the idea of space is neither an objective reality existing independently in the world nor a mere abstraction from sensory experience.

Space as an A Priori Intuition

For Kant, space is an a priori intuition, a fundamental structure of the human mind, a necessary condition for us to experience anything at all. It is not an empirical concept derived from experience, but rather the very framework that makes experience possible. We cannot conceive of objects without space, but we can conceive of space without objects. Therefore, space is "transcendentally ideal" but "empirically real." This means that while space is not a property of things-in-themselves, it is objectively valid for all objects of our intuition. This profound idea placed mathematics, particularly geometry, on firm ground, explaining why its truths are universally applicable to our experienced world.

Non-Euclidean Geometries: A Revolution in Mathematical Thought

The 19th century witnessed a seismic shift in the mathematics of space, challenging the long-held assumption of Euclid's fifth postulate.

Challenging the Parallel Postulate

Mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss, Janos Bolyai, Nikolai Lobachevsky, and Bernhard Riemann began to explore what would happen if Euclid's fifth postulate were denied.

- Hyperbolic Geometry (Lobachevsky, Bolyai): Through a point not on a given line, infinitely many lines can be drawn parallel to the given line. The sum of angles in a triangle is less than 180 degrees.

- Elliptic Geometry (Riemann): Through a point not on a given line, no lines can be drawn parallel to the given line. The sum of angles in a triangle is greater than 180 degrees.

These discoveries proved that Euclid's geometry was not the only logically consistent geometry. The idea that there could be multiple valid mathematical descriptions of space was a profound revelation. It shifted the understanding of space from a singular, intuitive reality to a manifold of abstract mathematical possibilities. The question then became: which of these geometries describes the actual physical space we inhabit? This question would later be answered by physics.

YouTube: "Non-Euclidean Geometry Explained"

Modern Conceptions: Abstract Spaces and Spacetime

The 20th century further abstracted the idea of space, detaching it from purely visual or intuitive notions and embedding it in rigorous mathematical structures.

The Abstraction of Space in Mathematics

Modern mathematics defines "space" in a far more general sense. It's often conceived as a set of points endowed with some additional structure. This allows mathematicians to study various types of spaces, each with distinct properties:

- Vector Spaces: A set of vectors that can be added together and multiplied by scalars, forming the basis for linear algebra.

- Topological Spaces: A set equipped with a "topology," which defines open sets and allows for the study of continuity and convergence without relying on distance.

- Metric Spaces: A set where a "distance function" (metric) is defined between any two points, allowing for notions of proximity and convergence.

- Hilbert Spaces: Infinite-dimensional vector spaces with an inner product, crucial in quantum mechanics.

These abstract spaces demonstrate that the idea of space is no longer limited to three dimensions or Euclidean properties. It's a versatile framework for organizing and understanding quantities and relationships, whether they represent physical dimensions, data points, or theoretical constructs.

Einstein's Spacetime

Perhaps the most dramatic redefinition of space in recent history came from Albert Einstein's theories of relativity. Einstein merged space and time into a single, four-dimensional entity called spacetime. This was not merely a mathematical convenience but a profound physical reality. Gravity, in this framework, is not a force pulling objects together but a curvature in spacetime caused by mass and energy. The quantity of space and time are no longer absolute and separate but are relative to the observer's motion and affected by the distribution of matter and energy. This transformed space from a passive backdrop into an active, dynamic participant in the universe.

YouTube: "Einstein's Theory of Relativity Explained"

Conclusion: The Enduring Idea of Space

The journey through the idea of space in mathematics is a testament to the human intellect's capacity for abstraction and discovery. From Euclid's foundational geometry, which codified our intuitive understanding of the world, to the profound metaphysical debates between Newton and Leibniz, and Kant's transcendental synthesis, the concept has continually evolved. The revolutionary insights of non-Euclidean geometries shattered long-held assumptions, paving the way for the abstract spaces of modern mathematics and Einstein's dynamic spacetime.

What began as a description of our immediate physical surroundings has transformed into a powerful, flexible mathematical tool—a quantity that can be manipulated, re-imagined, and applied to phenomena far beyond the visible universe. The idea of space, in all its philosophical and mathematical guises, remains a fertile ground for inquiry, constantly challenging us to refine our understanding of reality itself. It reminds us that even the most fundamental concepts are subject to reinterpretation, revealing the endless interplay between philosophy, mathematics, and our quest for knowledge.

📹 Related Video: What is Philosophy?

Video by: The School of Life

💡 Want different videos? Search YouTube for: "The Idea of Space in Mathematics philosophy"